OKAY. My Norton Critical Edition has taken up long-term residence on my nightstand and I am PUMPED to SET SAIL.

(Edit, 2022: These notes are essentially just me recapping Moby-Dick as I read it very slowly and deliberately over the course of what has turned out to be several years. I’m writing it primarily for my own benefit and posting it for the interest of about five people who might care. Lightly edited out of sheer embarrassment.)

Etymology and extracts

I suspect this introduction has a lot to say about what kind of book this is going to be. Most novels start with one or two epigraphs that are relevant to the story or themes. If you’re Steven King, maybe you’ll indulge yourself and stretch it out to five or six. Moby-Dick starts with A WHOLE CHAPTER OF EPIGRAPHS. There are EIGHTY of them.

Also, most authors present their epigraphs without comment. They just put them there in the middle of an austere, mostly empty page. NOT HERMAN MELVILLE. This guy has to make up a little story about where all this came from. Evidently he got his etymology of the word “whale” from a schoolmaster who died of tuberculosis (“a Late Consumptive Usher to a Grammar School”) and his cavalcade of epigraphs from a vanishingly minor drone at a public library (“a Sub-Sub Librarian”).

Given that the story hasn’t even started yet you might imagine that this, at least, is true. But it isn’t; neither of these people are real. Melville is already trolling us: he did all this research himself. And quite the accomplishment it is! Imagine trying to find eighty resonant extracts about whales in texts ranging from Shakespeare to ship’s logs without the help of the internet. This is a writer who’ll always go the extra nautical mile: no mere storyteller, but a person who Knows Stuff and has Read Things and Really Could Go On For A While.

So: let’s take stock, quickly. We’re ten pages in and we’ve already witnessed a gratuitous display of erudition, nested in a weird structure game where you can’t quite tell the real from the fake; the comical from the plain faced; the sane from the mad.

Onwards.

Chapter 1: Loomings

Richard Basehart in the 1956 movie version I haven’t seen.

This chapter is what made me want to read Moby-Dick. Before I picked up the book and read chapter one on a whim, I’d assumed that Moby-Dick was a somewhat bloated adventure story. This chapter immediately dispels that notion.

I read this countless times before I managed to move onto the second chapter. I love it; I love to read it out loud. That’s the way to really get your head around it. This book’s narrator, Ishmael, is simultaneously one of the most famous characters in fiction on account of this book’s famous first line, and somewhat underrated. He’s maybe my favourite first-person narrator ever, partially because he’s so hard to figure out. “Call me Ishmael” is a suspiciously phrased introduction, best read through narrowed eyes. I don’t think we’ll ever know this guy’s name.

But we can forgive Ishmael for being cagey, because he’s also a genius and a polymath with a manic fascination for language. He loves language so much that he often gets excited and uses more of it than he needs to. Catch him in one of his really good flights of fancy and he’s the personification of all the joy there is to be had in observing the world.

He is also traumatized. I’m not finished the book but I know as well as you do that it does not end happily. Ishmael is telling the story in retrospect, some years later, “never mind how long precisely.” Surely he didn’t emerge from his maritime ordeal unscathed. And there are tells, here and there. Look at the way he first brings up the whaling voyage that’ll be the whole subject of the book: “But wherefore it was that after having repeatedly smelt the sea as a merchant sailor, I should now take it into my head to go on a whaling voyage…” That sentence is the turning point of the chapter. It’s the first indication of what the story’s going to be about. And it’s just sitting casually in the middle of a paragraph. Ishmael can write super emphatically about all the abstract reasons why water is important (anticipating the best bit of Ulysses by almost 70 years) but he crab walks into the actual story with great hesitancy. I have a personal theory that part of the reason Ishmael beats around the bush so much and talks about pyramids and Niagara Falls and other irrelevant topics is that he’s actively trying to avoid telling the story for as long as possible, because it is going to be an emotionally taxing story to tell. Moby-Dick is a novel where a storyteller peels off an emotional band-aid as slowly and haltingly as possible. (Editing this in 2022, I’ve become aware that this is also a key thesis in the morally dubious new Darren Aronofsky film The Whale, which I probably won’t see, proving nonetheless that old adage about stopped clocks.)

There are indications that Ishmael had some issues before he ever set foot on the whaling ship that traumatized him. He proclaims, semi-jokingly, within the first few sentences of the book that he likes to go to sea “whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off.” This is CONCERNING TO SAY THE LEAST but it is also exactly what pulled me into the novel in the first place. I’m not sure how interested I am in revenge stories, maritime adventure, or obsessive captains. But I’m quite happy to spend some quality time with this narrator, no matter how reluctant he is to actually tell the story he’s ostensibly telling.

The other thing I love is that even though Ishmael clearly has some serious baggage related to his time at sea, he knows how good the story is. Look at how his language takes flight at the very end of the chapter, as he’s about to launch into the narrative proper: “the great flood-gates of the wonder-world swung open, and in the wild conceits that swayed me to my purpose, two and two there floated into my inmost soul, endless processions of the whale, and, mid most of them all, one grand hooded phantom, like a snow hill in the air.” How can you not love a guy who can conjure up that kind of wonder in relation to the worst experience of his whole life? “I am quick to perceive a horror,” Ishmael tells us, “and could still be social with it — would they let me.” We should all be so generous to our trauma.

In chapter one, we meet our mysterious, manic, melancholy guide through the tale of Moby-Dick. He tells us essentially nothing about the story or about his past life. But he does something much more profound and compelling: he shows us how his mind works. He tells us about why he loves the sea and why he loves being a lowly sailor rather than an officer. He tells us about the doldrums that take hold of him when he lingers too long on land. And, maybe half by accident, he exposes us to the sheer force and charm of his personality and makes us want to pay attention, whether he’s getting on with the story or not.

Chapter 2: The Carpet-Bag

This is what a carpet bag looks like. Whatever his many virtues, Ishmael is not a strong accessorizer.

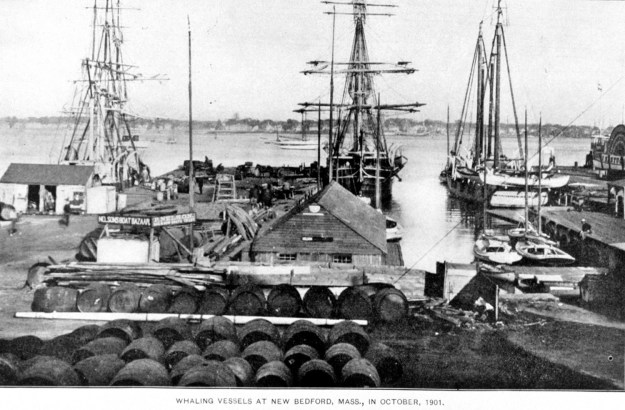

Ah, look! We have some honest-to-god story! Things Are Happening! Essentially, the next several chapters detail Ishmael’s wanderings in New Bedford, a whaling town that seems at this point to have superseded Nantucket in its industry prevalence. But Ishmael, being something of a Hipster Whaler, makes a point of expressing his disappointment in this fact. He is headed for Nantucket, thank you very much; nothing but the OG whaling port will do for a man of history such as our narrator. Still, he can’t help but start his narrative long before the action begins. So, we’ll follow him around New Bedford for a few chapters while he waits for something to happen. (When I said that Things Were Happening I was speaking in the broadest possible terms.)

In chapter two, Ishmael walks through the streets of New Bedford with his weird bag, looking for a decent place to stay. It contains one of my favourite comically overstuffed sentences in English. Ishmael means to say “I didn’t have much money, so I needed to find a cheap hotel.” Instead, he says: “With anxious grapnels I had sounded my pocket, and only brought up a few pieces of silver,—So, wherever you go, Ishmael, said I to myself, as I stood in the middle of a dreary street shouldering my bag, and comparing the gloom towards the north with the darkness towards the south—wherever in your wisdom you may conclude to lodge for the night, my dear Ishmael, be sure to inquire the price, and don’t be too particular.” Marvelous.

In any case, Ishmael settles on a place called the Spouter-Inn, which will make up the setting and title of the next chapter.

Chapter 3: The Spouter-Inn

Our narrator’s account of his arrival and first night at the Spouter-Inn contains a bunch of top-shelf Ishmaelisms about the weird painting by the bar, and one crucial plot element. This is the chapter in which we meet our first non-Ishmael main character: Queequeg, a cannibalistic harpooneer from a made-up island in the South Pacific who unexpectedly becomes Ishmael’s literal strange bedfellow.

Queequeg is a somewhat troublesome character, but let’s give Melville credit for what he’s trying to do, which is to present a character whose cultural difference from the novel’s white frame is an asset and not a deficiency. Nonetheless, best to acknowledge that some specifics of his characterization, particularly the pidgin English, do rankle a bit.

It’s telling that the first truly racist attitude we see in the novel comes from a thoroughly unsympathetic character: Peter Coffin, the landlord of the Spouter-Inn. (“Coffin” is a word which will come to take on a substantial significance for both Ishmael and Queequeg later in the book, which I know because I have cheated and read the epilogue.) Coffin is a jackass. He decides that Ishmael and Queequeg will sleep two-to-a-bed this night, and as soon as he makes that decision it becomes a huge private joke for him. Coffin’s well aware that Queequeg is harmless. Still, he insists on dropping cryptic, racist hints to Ishmael that his sleeping companion may in fact be mortally dangerous. So basically, before we get to know Queequeg through Ishmael’s more progressive eyes, we see him as he is seen by the bulk of the white Americans he interacts with: as a disfigured monster, a person so profoundly “other” that one cannot relate to him. It’s a thuddingly obvious point, but actually this book’s real disfigured monsters are both white.

At the end of the chapter, Peter Coffin’s practical joke pays off: Queequeg is startled to find a strange man unexpectedly in his bed, and Ishmael is mortally frightened to find himself in the company of a startled man he has every reason to think is a murderer. Hearing the commotion in the room where he’s paired them off, Coffin arrives to defuse the situation, and all is well. It’s as close as classic literature gets to farce without actually being a straight-up farce.

Chapter 4: The Counterpane

For the faint of sight: “Queequeg and his Harpoon”

Ishmael wakes up to find Queequeg’s arm flung around him matrimonially. Hmm, I wonder if I Google “Ishmael/Queequeg fanfic” what would OH MY GOD

This is the chapter where we’re introduced to the real Queequeg, as opposed to Peter Coffin’s made-up monster. Ishmael regards him as a bit of an archeological curiosity, which isn’t entirely progressive, but hey, we’re headed in the right direction.

Also, every time Ishmael shares a memory from before the start of this story, it is fucked up. First the thing about knocking people’s hats off in the street. Now this nonsense about him hallucinating a phantom hand as a child. The man is barely coping.

If it seems like I’m glossing over the plot, that’s because it still isn’t happening. You’ll hear no complaints from me.

Chapter 5: Breakfast

Ishmael descends from his room to eat a hearty morning meal. He generously forgives Peter Coffin for his skullduggery. He observes that you can tell how long a whaler has been ashore from his tan. And he complains that none of his fellow tenants at the Spouter-Inn want to talk at the table. It’s easy to assume, because he’s such a verbose narrator of the book that Ishmael is one of those people who never shuts up. But how could he have become so worldly-wise if he weren’t also an accomplished listener? I understand his frustration at this silent breakfast. These people clearly have stories. How DARE they keep it all to themselves. They’re depriving a writer of potential material. Shameful.

Chapter 6: The Street

I promise not to go long on this, but man, New Bedford sure sounds a lot like my hometown. I’m from Fort McMurray, Alberta, a mid-sized oil town in the frozen north. Like New Bedford, it is a place where the land itself is almost comically inhospitable and ugly. When Ishmael describes New Bedford, he tells us that “parts of her back country are enough to frighten one, they look so bony.” And yet, “the town itself is perhaps the dearest [most expensive] place to live in, in all New England.” He makes a big thing of how big and lavish the houses are in this landscape that ought to be desolate, all because of whaling: the mad slaughter that was at the time the fifth-biggest industry in the United States. All these mansions, Ishmael says in a cinematic turn of phrase, “were harpooned and dragged up hither from the bottom of the sea.” Sub out whaling for oil, and you’re pretty close to the place I’m from. Maybe that’s another part of what pulls me in.

Chapter 7: The Chapel

The present-day Seaman’s Bethel in New Bedford, on the same land as the previous one that burned down.

Ishmael and Queequeg spend the next three chapters in church. I understand the church they go to actually exists: it burned down in the 1860s, but has since been rebuilt. It was originally a church specifically for the whalers of New Bedford and their families, a place to go and pray that neither you nor any of your loved ones will get eaten by sea monsters. It’s a necessary public service, considering that death at sea was frighteningly commonplace. The main purpose of this chapter is to establish that fact. The memorial plaques on the wall of the chapel make us aware of the fact that we are following Ishmael on a journey of staggering risk. It’s Melville’s way of ratcheting up the tension, the way a fantasy writer might point out all of the human bones in the cave that the would-be dragonslayer has just entered.

It’s also one of the most powerful chapters in the book so far, clearly expressing the unique pain and uncertainty of losing a loved one at sea, with no body to serve as confirmation. As Ishmael observes the grieving families around the chapel’s memorials, he reflects: “Oh! ye whose dead lie buried beneath the green grass; who standing among flowers can say—here, here lies my beloved; ye know not the desolation that broods in bosoms like these.”

Chapter 8: The Pulpit

The one comedic factor that undercuts the power of these chapters in the church is that the chapel’s décor is super tacky. The pulpit is fashioned in the likeness of the prow of a ship, as if the pastor thinks the congregation needs to be reminded of who they are. There was a seafood restaurant like this in Fort McMurray, which is full of nostalgic expat Newfoundlanders. Rigging along the walls, part of a rowboat affixed to the ceiling. I always thought, how can this possibly be helping? Wikipedia tells me that the tacky pulpit was Melville’s invention and that the actual chapel was tasteful and neutral. But after Moby-Dick became a hit, they went ahead and installed a prow-shaped pulpit, proving that the Disneyland impulse to shape reality in accordance with fiction extends to the literary world as well.

A final observation: Ishmael opines that the pulpit is at the head of the world. The person giving a sermon is in the lead, and everybody else follows. Coming from Ishmael, this doesn’t feel so much like a display of religious conviction as a show of faith in the power of language. The pulpit is a place where speeches are made, and people act on those speeches. Before long, Ishmael will meet another excellent speaker who demonstrates the dark side of this power, and it’ll completely ruin his life.

Chapter 9: The Sermon

If the chapel’s decor was tacky, then Father Mapple’s constant use of sailor-speak is downright condescending. Nevertheless, his sermon is pretty clever. He starts off with a hymn: a whaling-inspired adaptation of Psalm 18 in the hymnbook Melville grew up with, in which a sinner is filled with fear and anxiety before finding salvation in prayer. For an even better version, with kickass piano and no happy ending, see Nina Simone’s “Sinnerman.”

After the hymn, Father Mapple tells the story of Jonah, which is A LITTLE ON THE NOSE YOU’VE GOTTA ADMIT. But he tells the story in a way that reflects the theme of Psalm 18, and also reflects Ishmael’s antipathy towards paying passengers in the first chapter: “In this world, shipmates, sin that pays its way can travel freely, and without a passport; whereas Virtue, if a pauper, is stopped at all frontiers.”

I wonder if this priest talks about Jonah every single Sunday. Maybe Ishmael and Queequeg just drop in on Jonah Day by coincidence. Maybe he alternates between Jonah and the whale and Noah’s ark. Surely this guy doesn’t have time for Bible stories about the desert.

Chapter 10: A Bosom Friend

First, the plot: Ishmael gets back from church, bonds with Queequeg, and worships a wooden idol with him: no small thing for a Presbyterian.

This is one of those chapters where my Norton Critical really comes in handy. Dr. Hershel Parker’s footnotes point out that the 30 pieces of silver Queequeg gifts Ishmael with are an echo of the 30 pieces of silver Judas received for betraying Jesus. Parker also informs me that, in spite of Ishmael’s admirable justification for joining Queequeg in his worship ceremony (he just thinks it’s nice to be friendly!) it is a blasphemous justification according to the conventional reading of Exodus (“I am a jealous god.”) So, 30 pieces of silver for a betrayal of the lord.

The footnotes also assert that Melville’s blasphemy was the second-most important reason why his writing career ended prematurely. The most important reason was piracy, but not the skull-and-crossbones kind; that would just be too on the nose. Just normal, boring intellectual property theft.

Chapter 11: Nightgown

This is presumably the chapter that makes people read Moby-Dick as a queer novel where Ishmael and Queequeg are fucking. Ishmael carefully elides any sexy business, but really he’s just leaving space for the internet to do its own nasty work.

Unrelatedly, I really love Ishmael’s point about us not being fully ourselves unless we have our eyes closed. It’s a way of shutting out the reality outside and constructing our own reality. Ishmael is a benign narcissist. His narcissism allows him to understand others better because he has fully taken stock of himself.

Chapter 12: Biographical

These pictures are from Rockwell Kent’s illustrated edition, which I mostly really like.

At last we get to hear Queequeg’s backstory. He’s the son of a king on a Pacific island that doesn’t exist in the real world. “It is not down in any map,” Ishmael informs us. “True places never are.” Sure.

Basically, Queequeg decided one day after an encounter with some white men who came by on a ship that he’d like to visit Christendom, learn what he can, and return to his people to help engender some kind of cultural exchange. So, he managed with great difficulty to convince the captain of the ship to take him to America. But soon he came to realize that white Christians could be cruel and venal and that this wasn’t his world. But at this point, his home island wasn’t home either. He felt he was too Christianized to rightly ascend his father’s throne. He is a man without a country: a seafarer who can live nationlessly aboard whaling vessels until he feels it’s right to go home. Much later, Ishmael will tell us that “in landlessness alone resides highest truth.” By that standard, Queequeg is the truest person in the story.

Chapter 13: Wheelbarrow

WE’RE MOVING. After eleven chapters in New Bedford, our narrator has finally set off for the OG whaling port of Nantucket on a schooner. He’s got Queequeg in tow and thank god for that, because his presence allows for AN ACTION SCENE.

One of the would-be whalers (Ishmael calls him a “bumpkin”) on the schooner dares to mock Queequeg, and he responds with a display of Jackie Chan-style comedy violence. Immediately thereafter, the ship’s boom comes detached: a problem Queequeg swiftly resolves in a whirlwind of jumping and lasso twirling. Ishmael finishes the chapter with great bluster, having now established that Queequeg is Spider-Man.

Do these tall tales of Queequeg’s derring-do strain credulity? Maybe. But remember what book we’re reading. You can’t quite tell the real from the fake; the comical from the plain faced; the sane from the mad.

Onwards.

To be continued.