I’m writing this shortly after the release of Betrayal at Club Low, the latest game from the indie developer Cosmo D. By the end of this essay I will have played it: an exciting thing, because every new Cosmo D game depicts another corner of magnificent, scenic Off-Peak City. It’s common enough to see a world develop over multiple video games. It’s rarer to see this happen with a world that’s almost entirely the product of one person’s dreams and preoccupations. As a fictional world, Off-Peak City isn’t governed by the traditional tenets of worldbuilding: history, laws, etc. “Lore.” Instead, it gets its consistency from its unmistakable atmosphere and a handful of recurring reference points. You know it’s Off-Peak City because of the music, the architecture, the way people talk, the way images look, the board games, the great stone faces, the pizza. You may not understand what’s going on. But actually you do, because the understanding is in the looking and the listening.

I really adore Cosmo D’s work. The Norwood Suite in particular is a game I’ve replayed many, many times. When we talk about a game being replayable, sometimes what we mean is that the game changes significantly on a second or third playthrough. We say this as if movies aren’t rewatchable in spite of being the same every time. I find Cosmo D’s games rich, immersive, and satisfying. So, before I crack into Betrayal at Club Low, I’m going to revisit the catalogue and make some notes as I go. I’m not aiming to exhaustively annotate these games, and I don’t really have an argument I’m trying to make. I’m just going to take another stroll through these beloved old streets and hallways and point out a few of the things that fascinate me the most. Consider this a field guide to the world of Cosmo D: a tour led by a fellow traveler who shares Cosmo’s obsession with music, his love for the surreal, his irresistible impulse to put his obsessions on display, and perhaps his nagging sense that this impulse may be shallow.

Cosmo D has released five games at the time of writing:

- Saturn V, an early experiment that’s very short and simple

- Off-Peak, a short freeware title

- The Norwood Suite, his first commercial game

- Tales from Off-Peak City Vol. 1, the most polished of his first-person adventure games

- Betrayal at Club Low, a third-person RPG

(A quick note here that these games are unspoilable in my opinion, but many will differ on this. Full spoilers ahead for all five games. More to the point: if you haven’t played these games, this may be a challenging read.)

So, let’s begin our tour a billion kilometres away from Off-Peak City, orbiting another world altogether.

Saturn V (2014)

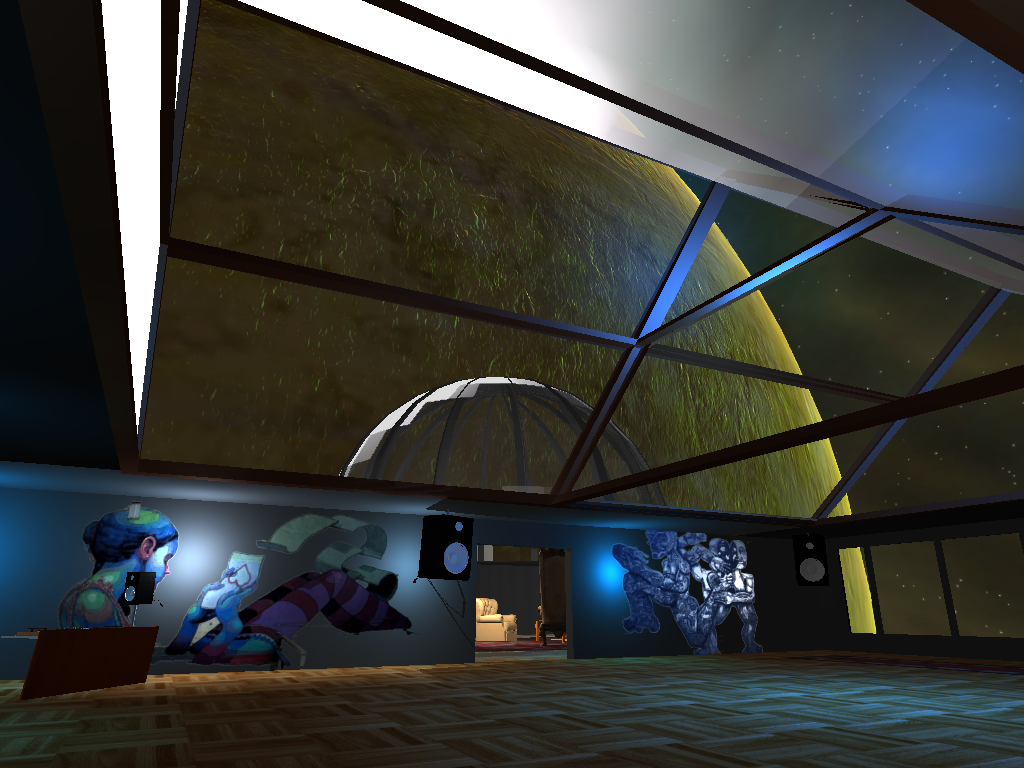

In 2013, while nursing a leg injury, the cellist and electronic musician Cosmo D started making a game. Naturally, the impetus was music. Saturn V is an illustration of the song of the same name by Cosmo’s experimental dance band Archie Pelago. It presents you with a simple, three-floor museum space to explore. As you do, different facets of the title song drift in and out of the mix. When you’re done, you can simply hit Esc to close the app. There is no ending in Saturn V, no confirmation that you’ve finished the experience you were meant to have. Narrative is absent here, and the only character present is you. You’re left to wonder about who put all this together, for what purpose, and how it all came to be orbiting the planet Saturn, visible through the massive skylight over the top floor.

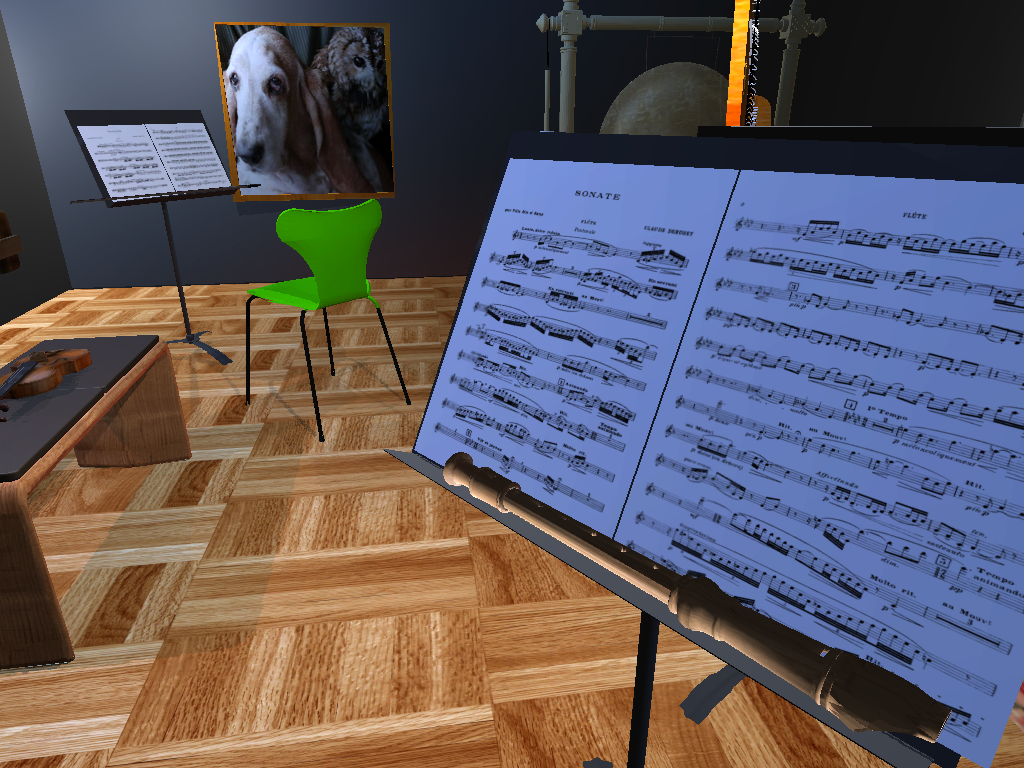

The orbiting exhibition contains many surprising things. Period maps of New York and Brooklyn. A Pringles can: sour cream and onion. Homer Simpson is here, three-eyed and courting a cease-and-desist. Near the entrance, you’re greeted with something I thought was the box art from an old edition of Turbotax, but which is in fact the poster for a Brooklyn-based DJ night. Around a corner you’ll find a rehearsal space, where Debussy’s Sonata For Flute, Viola and Harp sits on a trio of music stands. (I’m listening to this piece as I write. It’s C-tier Debussy in my opinion, but even C-tier Debussy is worth your time. He didn’t write much chamber music, so fill your boots. This recording is good.) Oddly, there is no flute present in the exhibition. There is a recorder. Perhaps somebody attempted to play the Debussy sonata on that. Perhaps that’s why this place is deserted.

A generous assessment of this exhibition would be to look at it as a sort of mood board. But taken that way, it doesn’t amount to much. Really, it’s an assertion of identity, cobbled together through things Cosmo D and his bandmates enjoy. Board games. Craft beer. Fashionable music (and also Debussy). It illustrates the modern tendency to define ourselves by what we consume, rather than what we produce.

The top floor of the museum ceases to be a museum altogether. Its three rooms contain a dancefloor, a plush living space, and a desk with a mixer and a computer running a DAW. What is this place? Did an Off-Peak City malcontent launch a satellite? Is this somebody’s off-world live/work space? A bachelor pad, for somebody who requires more distance from the city than the Hotel Norwood affords?

This is a ridiculous exercise, what I’m doing right now. It’s foolish to try and establish the canonicity of Saturn V, because it’s foolish to even consider it alongside Cosmo D’s later work. Comparing The Norwood Suite with Saturn V is like comparing a feature film with a MySpace page. Nevertheless, like all false starts, it tells us something about its creator. To a degree, each one of Cosmo D’s games is another Saturn V: another digital space in which to exhibit his tastes.

Off-Peak (2015)

A year later, Cosmo D’s second game gave us our first real glimpse into his emerging fictional world. This game is also built around an exhibition space full of things Cosmo likes, but there’s an intermediary between Cosmo and his creation now. Saturn V was built specifically to reflect the personalities in Archie Pelago, and the sensibility of Cosmo D himself. This time, the developer has punted some of the responsibility onto a fictional character: the curator of the exhibition you enter when you boot up Off-Peak.

In Off-Peak you wander through a train station managed by “a born tycoon” named Marcus. Marcus presides over the tracks from a raised lookout, flanked by palm trees, bodyguards, and two cows he strokes like trained tigers. There aren’t very many people milling about on Marcus’s premises. It’s off-peak hours, after all. One suspects it’s off-peak hours forever at this particular train station. You’re told that only the extremely wealthy can afford to travel through here. Really, the trains aren’t the point. The point of this place is the cluster of niche merchants who’ve set up shop here with Marcus’s imprimatur. The passengers on these trains are the sort of people who can keep a merchant afloat for two months with the purchase of a single, exorbitantly-priced vinyl record. This is the sort of place where a struggling musician comes to put their unused sheet music up for consignment where it can be sold to the weekend warriors, the easy marks among the wealthy commuters.

The good news is, you’ve got a shot at boarding the next train. All you have to do is find the eight pieces of a torn-up ticket, destroyed by a lap steel player in an act of self-sabotage. As you search, you discover that Marcus’s aesthetic is curiously similar to the one we witnessed in orbit around Saturn. There’s a lot of craft beer and board games. Crates of vinyl. Miles Davis. Sun Ra. There’s a copy of Laaraji’s hammered dulcimer masterpiece Day of Radiance here, which delights me every time.

The accoutrements of classical music are strewn about everywhere. One thing I’ve learned from going to music school, being a record collector, and working in classical music radio is that different groups of people look at classical music from such dramatically different angles that they’re not even really talking about the same thing. There’s the classical music people know by osmosis (The Four Seasons, the Queen of the Night’s aria, Also Sprach Zarathustra). There’s the stuff that the enthusiasts love and tend to assume everybody knows, but they don’t (the Beethoven late quartets, Monteverdi, Peter Grimes). And then there’s the music that is familiar to everybody who’s ever gone to music school, but which only musicians care about. It’s this last category that predominates in Marcus’s domain. As a lapsed trumpeter, I was retraumatized by the sight of Jean-Baptiste Arban’s method book just sitting innocently on a shelf in a video game. Likewise for the Aritunian and Hummel trumpet concertos: works that everybody who played the trumpet, or knew a trumpeter in university knows very well, but which are miles outside the repertory. (Deservedly so in the Aritunian’s case. It’s dreadful, albeit fun to play. The Hummel rules.)

Some of the people in this train station are flat-out insufferable. The ramen vendor is a former violist, who waxes violently poetic about how his new life cooking ramen is just like playing in an orchestra. And don’t get me started on the sheet music salesman. He can’t read music, but he knows what will sell. Most people here are trying to be Marcus. They’re scraping by, but they’re just one lucky break from transforming their own exquisite taste into a chic capitalist bonanza. There’s only one sympathetic character in this whole station. She gives away stale cookies in the subway. “I don’t care about fancy beer or personality pizza or tricky card games,” she says. Here, far from Marcus’s gaze, is the one person who recognizes the slightly sordid quality of this whole enterprise: art, repurposed as a lifestyle brand. She’s the figure who keeps Off-Peak from becoming a self-congratulatory ode to connoisseurship, a celebration of extravagant commerce.

Am I hopelessly old school, to side with this person so emphatically? Naïve, perhaps? I suspect Cosmo D, who put in years as a gigging musician, has a more nuanced perspective on this than I do. His games consistently deal with the relationship between art and commerce, and the decisions that artists have to make for financial reasons. But the forces of commerce are not purely malignant in this universe, nor are the artists entirely virtuous.

Marcus is one of two concentrations of power in Off-Peak. There’s also a circus passing through. They’re a big deal in these parts: the station entrance is lined with posters featuring trapeze artists and tigers, emblazoned with the Polish word for circus, “cyrk.” You learn about the Circus in dribs and drabs. They employ giants, and mistreat them grievously. They’ve got some sort of arrangement with the city. They have a lot of money, but they hire bands to tour with them and pay in “exposure.” Giants drink for free at the station bar, because the Circus pays their tab. It’s said their leader passes through the station at the same time every day. Red hair, orange dress, surgical mask. Can’t miss her.

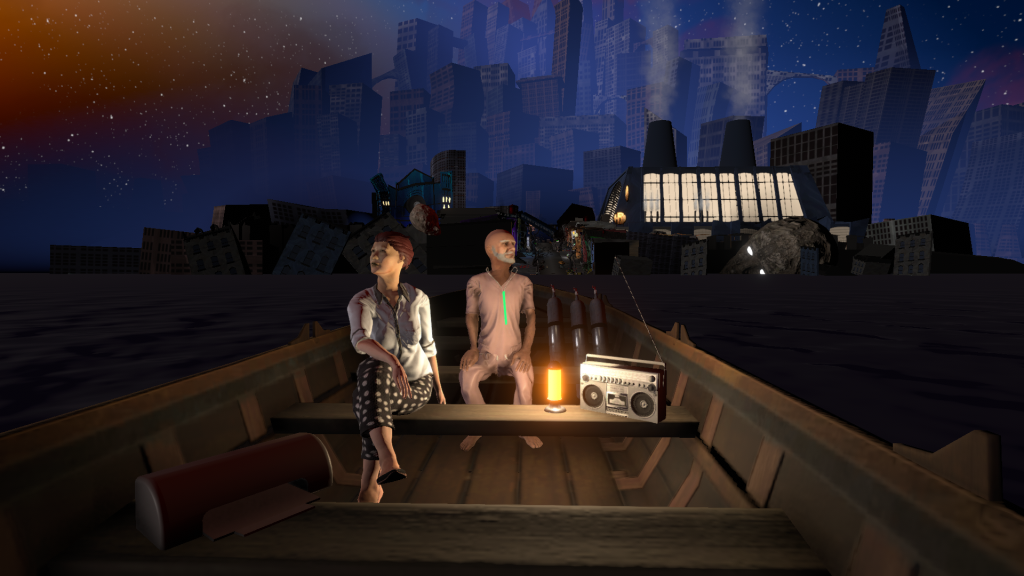

Her name is Murial, and she is to this game what the escape key was to Saturn V. Once you’ve finished your explorations, reassembled your ticket and–if you’re any fun at all–stolen as many records, music books and pizza slices as you can get your sticky fingers on, it’s time to board the train. Marcus stops you. That ticket isn’t meant for you, and it’s very expensive. Besides, you’re a thief, probably. The only thing for it is to enter into indentured servitude and work off your debts behind the ramen counter, like Conway at the distillery in Kentucky Route Zero. Enter Murial, holding a glowing white stag head. You’ve seen one of these before; it teleported you some distance. And it does the same now, as you bamf suddenly from the train station into a rowboat with Murial and three triplets who’ve been watching you this whole time. Murial welcomes you to the Circus.

There’s a lot in this game that isn’t fully explained. Part of that is a tease, that more will be revealed in the future. (Off-Peak’s final screen is a promotion for The Norwood Suite.) But I think it’s a mistake to regard these games as mysteries or riddles. I don’t really think it’s fun or enlightening to try and render them down to a single, stable, internally consistent narrative interpretation. Cosmo D’s later games become increasingly concerned with narrative and continuity, but Off-Peak functions best as a gallery show, with its various contents speaking to each other in abstract terms. In that sense, it is a much more successful exhibition space than its predecessor.

So. You’re in a rowboat with Murial. She doesn’t bring it up immediately, but she’s got a job for you at an old friend’s place.

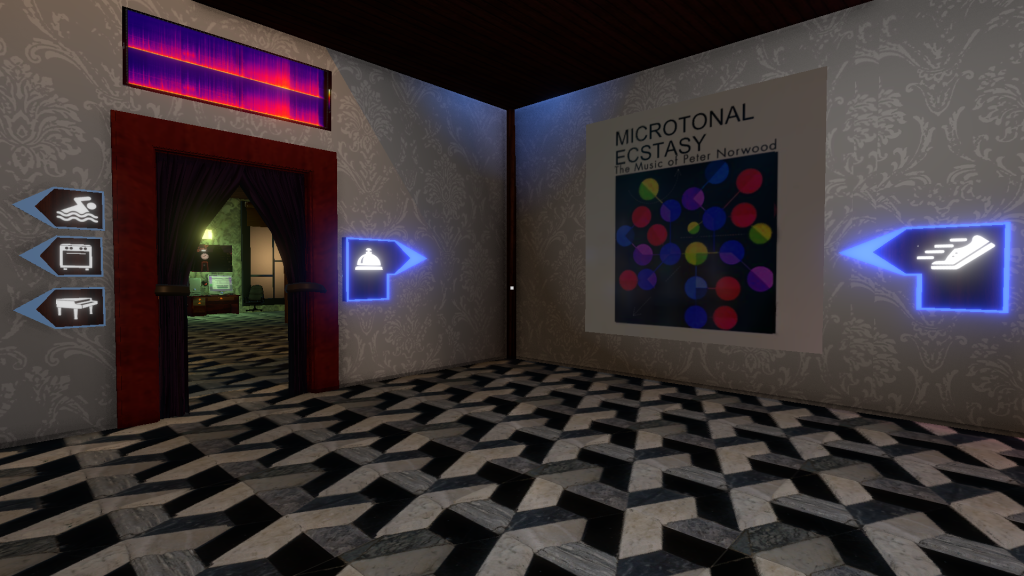

The Norwood Suite (2017)

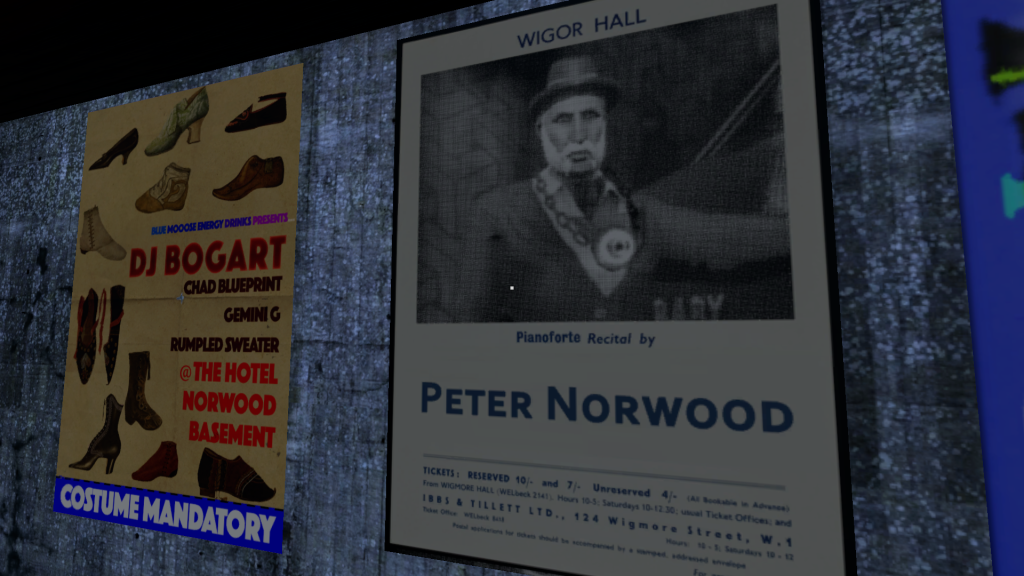

The Hotel Norwood is a crumbling gaiety, a haunted funhouse and pilgrimage site for the overambitious and fanatical. Once upon a time, it was a residence and base of operations for Peter Norwood, a pianist and composer with a cult of personality that has endured long past his mysterious disappearance in 1983. Now, it is a poorly-run hotel whose main clientele consists of Norwood acolytes and young people who arrive there for the ongoing dance party that one DJ Bogart has been throwing in the basement for nearly a year.

(Yes, this is a story about a long-vanished classical musician and a presently ubiquitous DJ, which sounds like the setup for a story about how the old ways were better. Mercifully, it isn’t: that whole notion is so foreign to this game that it doesn’t even consciously subvert that idea. It just cheerfully ignores it altogether and treats all forms of musical endeavour as potentially equal.)

You arrive at the Hotel Norwood on an errand for Murial, blue-haired now, like Oscar the Grouch turning green in season two of Sesame Street. The details of your job are hazy, but your gameplay objective is clear: you must simply explore this place. Take in the sights at this sprawling old house, just like in Gone Home or Resident Evil. (The Hotel Norwood shares the dramatic central staircase of both.) Inevitably, you will eventually have to Collect Five Things, or however many piano keys and costume pieces there are lying around. But for now, just learn about the people who are here. Learn what’s going on at this hotel.

It’s easier than you might expect. Your character in The Norwood Suite is entirely nondescript. In Off-Peak, people occasionally recognized you. Marcus had seen you come through before. You had a routine, and a past. But apparently now you’re such a cipher that nobody thinks twice about asking you to bring them a sandwich, in spite of the fact that you don’t work at the hotel. Nobody thinks twice about telling you all of their secrets and plans. It turns out you’ve arrived at an important moment for the Hotel Norwood. There’s a board meeting tomorrow, which will determine whether or not the hotel will be sold to a company called the Modulo.

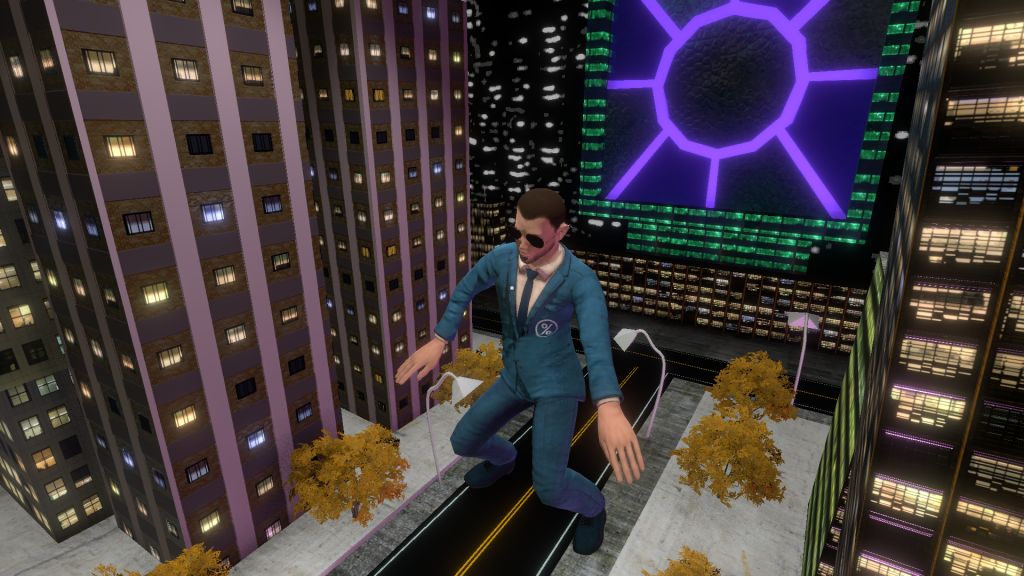

I’m not sure what the Modulo actually does. This is by design: they are an anonymous, megalithic corporate entity of the sort that is so often the antagonist in video games. They aren’t whimsically unknowable like the Circus in Off-Peak. They’re just vague. They wear blue suits emblazoned with the percent symbol. They carry around a ridiculous company manual. They actively recruit young artists away from their music careers. And most crucially, they want to turn the Hotel Norwood into a server farm. I like some of the Modulo folks I met at the Hotel Norwood. But I’m also sad about the Vancouver post office that’s being redeveloped into cubicles for Amazon. And that’s a post office.

The more people you talk to, the more likely it sounds that tomorrow’s board meeting will play out in the Modulo’s favour. The hotel staff are disconsolate and afraid for their jobs. The Modulo’s legal team is up late crossing t’s, dotting i’s. Alan Miranda, the white knight lawyer hired by the hotel’s manager Nadia to convince the advisory board to vote against the Modulo, is trying to manage expectations. Granted, he says he’s got an ace in the hole. We never find out what it is. It’s a cast of night owls, up late out of inclination or necessity. The Blue Moose flows freely, effervescing like television static. (Saturn V was littered with Red Bull cans; this time Cosmo has disguised it ever so slightly. Blue Moose energy drinks are everywhere in The Norwood Suite, like a comedic ad read in a parody podcast. They’re the official sponsor of the dance party in the basement. Their company representative is officially neutral on the subject of tomorrow’s board meeting, but he’d really prefer if the Modulo didn’t stop the party. Opposing corporate interests. One of these stopped clocks is presently correct.)

If the Modulo gets their way, the Off-Peak City metropolitan area will lose a significant piece of cultural heritage. Just like the train station in Off-Peak, the Hotel Norwood is a reflection of one specific person. But unlike Marcus, Peter Norwood was no mere tycoon: he was an artist of great renown. But who was he exactly? Well for one thing, he was Glenn Gould. Cosmo D has made this explicit, but the parallels are obvious regardless. Gould and Norwood are both eccentric cult figures, private and mysterious people whose lives and personalities revolved around playing the piano. Both of them stopped performing live at the peak of their powers. And Norwood’s mysterious disappearance in 1983 coincides roughly with Gould’s death in 1982: just different enough so it’s not too on the nose. More important than any of this, Norwood and Gould are both cool. The hotel walls are hung with Norwood’s album art: tasteful, minimal, reminiscent of 1960s jazz covers and Penguin paperbacks. Like Gould, Norwood was a genuinely modern classical musician, not a bland totem of sophistication.

But Norwood is also Miles Davis, Charles Mingus and every other Whiplash-esque hard taskmaster bandleader. He’s Rodriguez, missing and presumed dead. And he’s David Bowie, not just because of the glammy outfit. I think about the movie Velvet Goldmine every time I get to the end of The Norwood Suite. It’s a Bowie biopic with the serial number filed off, directed by Todd Haynes. The movie is preoccupied with the moment Bowie cast off his Ziggy Stardust persona (captured on tape and film by D.A. Pennebaker). Velvet Goldmine tells the story of the rock star Brian Slade, a fictional character clearly modelled after Bowie. Slade vanished after unsuccessfully faking his own death at a concert, in a moment that clearly resembles Bowie’s fake retirement in 1973. At the end of the movie, the reporter we’ve been following throughout comes to believe that Slade is alive and well and has transformed into another person entirely: Tommy Stone, a nakedly commercial pop star who resembles Bowie’s Let’s Dance-era supercelebrity persona. The film is tinged with Todd Haynes’ disappointment in Bowie, that he could abandon the gay community who propelled him to success as Ziggy Stardust, just as the AIDS crisis was beginning. More generally, it’s a movie about how artists usually function better as ideas than as people. The real David Bowie agreed. He says so himself in the new documentary Moonage Daydream: what’s at an artist’s core doesn’t matter as much as the way they bounce around in listeners’ heads. He’s talking about Dylan, Lennon, Iggy Pop and himself. Add Norwood to the list.

The ending of The Norwood Suite is even more elliptical and strange than the ending of Off-Peak. Once you’ve Collected Enough Things, you find your way into the titular Norwood Suite, an off-limits area that was once Peter Norwood’s private quarters. At this point a few things fall into place. You learn that your employer, Murial, sent Norwood a vinyl record sometime in the early 80s, not long before his disappearance. By sheer coincidence, that exact record has found its way back to the Hotel Norwood on this very night, in the possession of a music teacher who’s conducting a field trip. Once she’s able to play it, you learn that the record’s contents are barely music at all. It features an automated voice reciting a series of numbers. The next time you hear this voice reciting these numbers is at the very end of the game. You’ve made it into DJ Bogart’s private suite and presented him with Murial’s mix CD. (This was your mission, it turns out.) Upon hearing this voice, DJ Bogart’s head duly explodes, revealing him to be some kind of automaton wearing a human shell. The implication is that what’s happening to DJ Bogart in this moment also happened to Peter Norwood many years prior, also thanks to Murial.

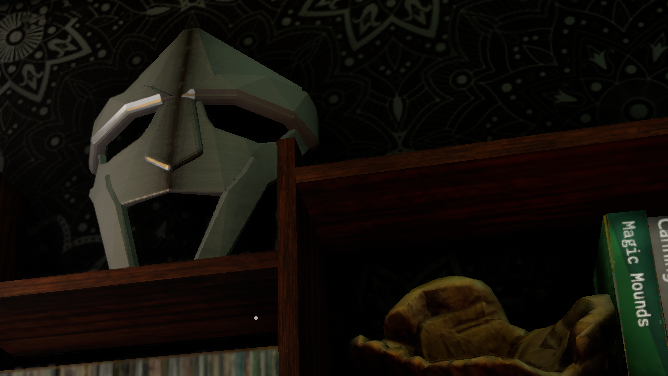

The further implication is that Norwood and Bogart are fundamentally the same. Even if they are not literally the same person, they are different personas of the same larger entity, different facets of the same force. They are the same person in a similar way that Brian Slade and Tommy Stone are the same person in Velvet Goldmine. One is an esteemed artist and the other a vessel for corporate sponsorship, but maybe that’s not as important a distinction as it initially seems. To drive the point home, the game ends with a member of Norwood’s old ensemble, an elderly paraplegic harpist, Dr. Strangeloving right up out of his wheelchair and dancing past the smoldering remains of DJ Bogart, straight towards you. For the final act of the game, you’ve been wearing a Peter Norwood costume, complete with mask and monocle. What the old man doesn’t recognize is that he’s in the presence of two absences. DJ Bogart is now quite clearly a machine, a nonhuman. But Peter Norwood is just a costume. And inside that costume is a person so nonspecific that they are routinely mistaken for hotel staff.

What precisely this means is slippery, and it should be. The Norwood Suite is a game that’s preoccupied by the relationship between art and commerce, but you can’t sum up its thesis statement on that topic in a neat line. And it’s wrong to fixate on the ending specifically: the themes are woven throughout. Most of the musicians you’ve met at the Hotel Norwood have fraught relationships with their art. But there’s no sanctimonious judgement here of artists who “sell out.” All of the contempt in the game is reserved for the Modulo: a company that forces concert venues to close and turns magnificent heritage sites into server farms. It’s companies like this that make conditions for artists so challenging in the first place.

The Norwood Suite leaves many lingering questions that Steam communities and subreddits will be more inclined to resolve than I am. Why is Murial consistently pictured as a member of Norwood’s ensemble, when they almost certainly never played together? What is Alan Miranda’s ace in the hole? Why can the old harpist suddenly walk? What happens at the board meeting? (This last one is answered in the following game; it is as we’d feared. The Modulo wins the day.) More power to anybody who wants to figure this stuff out, but as with Off-Peak, I prefer to look at The Norwood Suite as an exposition space for a constellation of ideas, images and sounds. It is Cosmo D’s most sophisticated exposition to date, because it is not primarily a display of excellent taste. (Not primarily.) There are still board games everywhere, but they’re part of the character drama, not just aesthetic signifiers.

Even more remarkably, there are almost no name drops of real-life musicians anywhere in this game. Off-Peak was packed with music school shibboleths and cred-building obscurities. The Norwood Suite basically ignores the entire history of music and exists in its own totally fictional musical reality. Sure, there’s a blown-up print of a gigue from one of Bach’s cello suites on the wall. But it doesn’t have his name on it. Yes, the dialogue does reference a composer named “Xenokos,” which sure sounds like Xenakis, but it isn’t quite. Likewise for “Froburger,” who isn’t quite Froberger. The briefly discussed “master of the pocket symphony,” Broomes, has a name that sounds like Brahms but that’s where the similarities end. No doubt there are a few things I missed, but I only caught a couple of references to genuine historical figures. One is to the utterly obscure Hungarian pianist and inventor Emánuel Moór.

The other, much more consequential, is that the Hotel Norwood’s manager is named Nadia Boulanger. The historical Nadia Boulanger was a legendary pedagogue who taught musicians ranging from Aaron Copland to Quincy Jones. Astor Piazzola. Philip Glass. Boulanger judiciously refused to teach George Gershwin, sensing that he basically had it all figured out. She was a skilled composer in her own right, though not a confident one, and always in the shadow of her talented sister Lili who died young. Nadia’s opera La ville morte has been produced exactly twice, and is pretty good. What connection this figure is meant to have with the ruthless, scheming, borderline abusive manager of the Hotel Norwood is beyond me. But it seems meaningful to me that the one figure from music history that Cosmo D chooses to include in this piece is a massively consequential figure who is nevertheless somewhat marginalized and not recognizable by name.

The Norwood Suite engages with the history of classical music in a way that no other piece of media ever has, to my knowledge. It does not mention the name of a single canonical composer. This is remarkable. Usually when classical music shows up in media, it’s there specifically to trade on its familiarity. Mozart and Beethoven are easy stand-ins for the abstract idea of genius, and familiar works by Tchaikovsky and Strauss serve as shorthands for gracefulness or gravity. This tendency to emphasise a familiar handful of marble faces and iconic tunes is frustrating to those of us who’ve been on our own journeys of discovery with classical music, and to anybody who cares about representation. And here comes The Norwood Suite, which is full of fictional musicians of various genders and races and not a Beethoven reference in sight. Among everything else The Norwood Suite is doing, it is also a vision of what the culture surrounding classical music could look like if it weren’t organised around the canon. I’ll admit, this is what fascinated me about this game in the first place. I love that it depicts people who are writing string quartets, practising etudes and restringing their harps, and whose heroes walked the earth at least in living memory.

The rough precociousness of Cosmo D’s first two games is gone without a trace. He started off making virtual spaces to display stuff that he and his friends liked. In The Norwood Suite, he’s tempered that impulse so thoroughly that I just spent several paragraphs praising its lack of reliance on historical references. The Hotel Norwood feels like it emerged organically from its own fictional world. It’s an impossible place that feels absolutely real and it makes me feel completely at home.

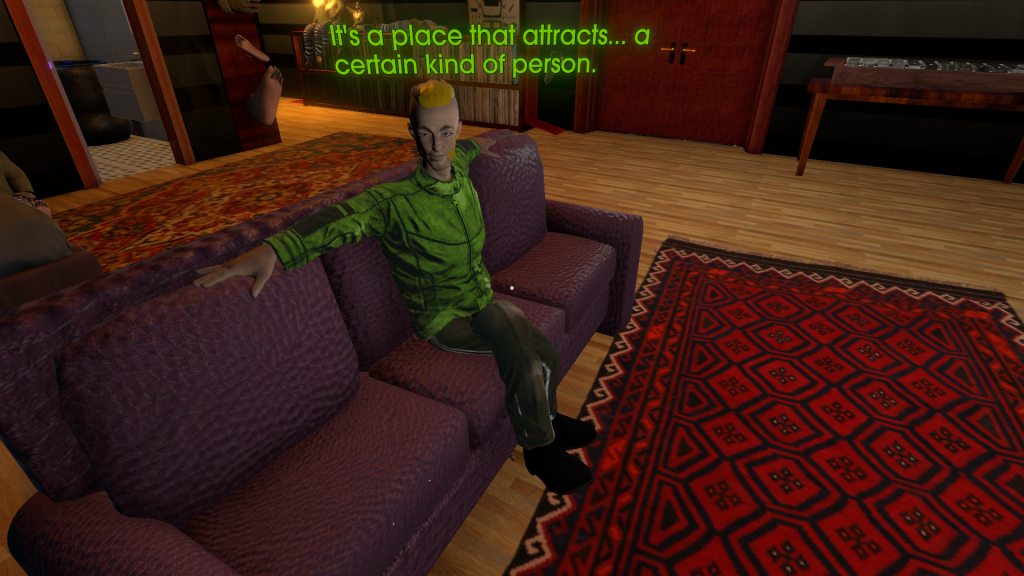

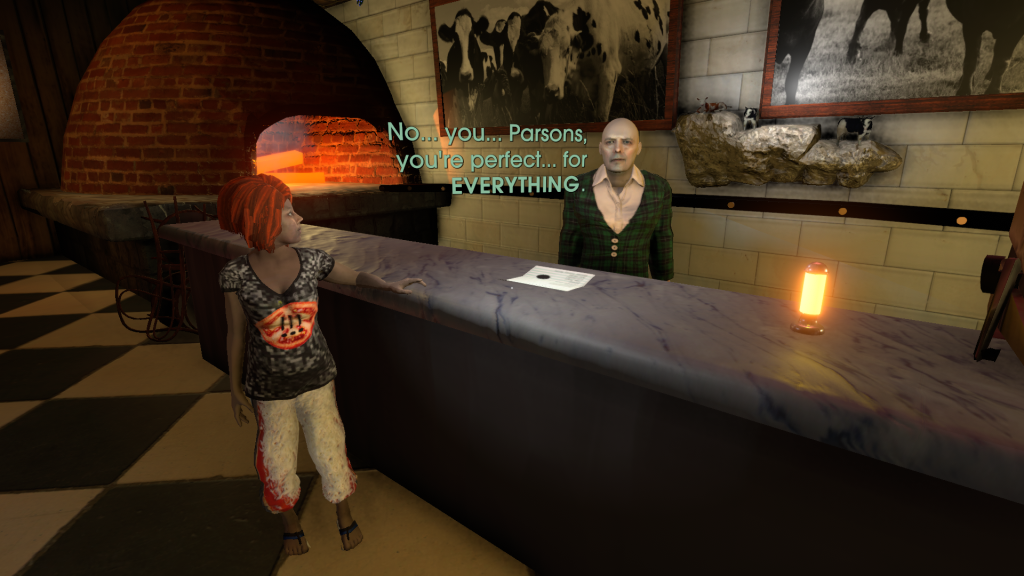

Tales from Off-Peak City Vol. 1 (2020)

For the second time in a row, you’re being dropped off by the last person you saw. Murial dropped us off at the Hotel Norwood in a rather practical car. But traffic isn’t running to the intersection of Yam and July. The neighbourhood is drastically flooded, so you find yourself drifting onto the sidewalk in a rowboat, along with the elderly harpist who accosted you at the end of The Norwood Suite, and his more articulate daughter. They need you to steal a saxophone that’s locked up in the basement of a pizza joint. Fine. Par for the course. But what’s more interesting is that they ask for your name. This time, you’re not going to be a cipher. This time, you’re a somebody.

The fact that you actually get to choose your character’s name this time is no trivial thing. Tales is a game that’s adamant that you’ll express your identity throughout this story. This time you won’t just explore. You’ll apply your will to the world. You’ll make things. So I guess it’s finally time to talk about gameplay. I poked fun at Norwood’s gameplay macguffin of Collecting Things. (Off-Peak is the same.) And sure, Collecting Things is a bit of a cliché, but in that game your actual objectives are so hilariously incidental to the experience that it feels like missing the point to criticize this. Nevertheless, Tales tries a new approach. There’s still a fair bit of exploring the world to collect items that will serve as keys to get you into new areas. But Tales also sends you on missions, like the tiny open world game that it is.

Specifically, it sends you out delivering pizzas. Almost as soon as you disembark from the rowboat, you find yourself employed at Caetano’s Slice, a restaurant run by the former saxophonist you’re assigned to steal from. While you try and work out a way to get into his locked basement saxophone vault, you may as well make a little money delivering pies. Also, you’ll have to make them–and this is the game’s first invitation to really express yourself.

The pizza making minigame is a simple little thing that I find unreasonably fun. The orders that come into Caetano’s shop read like Oblique Strategies. “Right in the chest,” for example. Lots of room for interpretation. Will you serve your customers elegant, traditional margherita or pepperoni pies? Or will you load them up with more outré toppings: flamingo meat, chocolate chips, gummy worms, synthetic brains? (Given these, the lack of pineapple feels like a deliberate provocation.) Every ingredient is tied to a different instrumental loop in the score. The more sauce you use, the more bowed cello you hear. More gummy worms, more jaw harp. It’s a kind of interactivity Cosmo D has been interested in since Saturn V, where moving from room to room changed the mix of the soundtrack. Better still, there’s actually a physics simulation here, so if you pile on too many slices of buffalo mozzarella (and who can resist), they will tumble off onto the floor.

Upon delivery, your customers will assess your creation, ingredient by ingredient, praising your good taste or raising an eyebrow at your more innovative pies. (There must be an impressive amount of writing under the hood here, to account for every ingredient in various quantities.) Whatever the verdict, your customers always eat their order in the end. As ever, there’s no way to fail in this game. If you want your road to success to be paved with chocolate chip and olive pizzas, so be it. This is the first time in this universe where your choices determine what people say to you. It’s only right that the subject should be pizza toppings.

But even before you get your new job, the game offers you another expressive tool: a camera. Even the most beautiful video games can force you into a utilitarian way of looking at the world around you, just scanning for valuable information. The fact that Tales gives you a camera right at the start of the game encourages you to find compelling angles from which to look at the world, to make the act of moving through the world into a creative one. (Coincidentally, this mechanic is the central feature of Umurangi Generation, an indie game that came out the same week as this one.) For two games, Cosmo D has placed us at the beck and call of self-conscious creatives. Gameplay is an implicitly creative act, but the player’s creativity is more integral here than in any of Cosmo’s previous games. This time, we feel embodied. We’re here. When you play all of Cosmo D’s games in a relatively short timespan, you can feel the focus gradually shift from the developer, to the characters, to the player: from me, to them, to you.

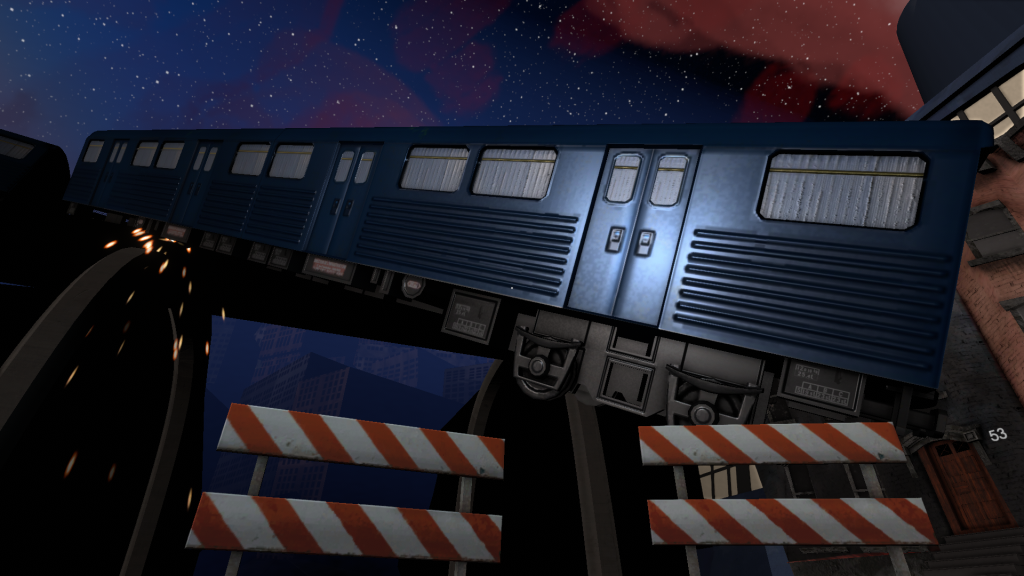

Granted, the place we’re here to photograph is in rough shape. The intersection of Yam and July is a neglected part of town, ignored by its elected officials and physically cut off from its surroundings. Two sides are cut off by the flooding, one by an oddly meticulous pileup of cars. And to the north, a train car dangles precariously off its elevated tracks: an ongoing catastrophe that everybody’s sort of gotten used to. Video games necessitate these kinds of barriers, to keep you from moving into the part of the world that doesn’t exist. But here, those barriers serve as jokes, and also as a way of communicating what kind of place this is. These limitations mean something to the people who live here. Luke the music professor can’t get to his classes because the trains aren’t running. The folks who fish in the canal aren’t catching anything because the floods let all the trout escape.

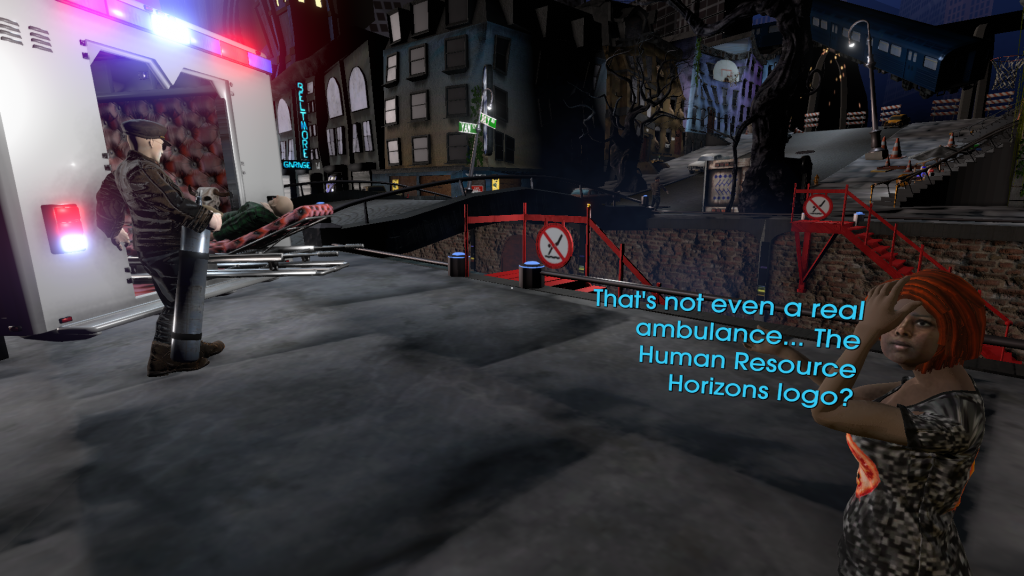

But city hall is hardly their biggest problem. Like Off-Peak and Norwood, Tales has its own shady organization that looms over the story–quite literally, in fact. The factory run by Human Resources Horizons is the largest building in the area, and its massive white-lit windows are the first thing visible from your rowboat as you drift into the city. The man in charge of HRH, Big Mo, is functionally in charge of this neighbourhood. He’s the first person you meet when you get off the boat, before you get your job and before you even get your camera. He commands an army of wan-faced goons, all alike, who we’ve actually been running into ever since we first set foot in Marcus’s train station. HRH isn’t just a company, it’s a sort of extra-judicial law enforcement agency. The shady organizations of this world are becoming ever more worrisome. Remember when we first heard about the Circus? And they just seemed like a sort of dodgy arts collective? Even the Modulo wasn’t disappearing people.

HRH looks poised to become the ultimate villain of this saga. But all our shady friends are still here. The Circus is sharing an office building with Blue Moose R&D. (We get a tantalizing glimpse of Murial through a crack in a door, her only appearance here.) The Modulo is still present and working its people into the ground. Even Marcus makes an appearance, trying to coerce a naïve young band into an exploitative handshake deal. But some of the familiar faces seem less familiar than you might expect. Part of it is just that the character models have improved so drastically since Norwood that everybody suddenly looks 70 percent more alive. But there are other red flags. Jeremy played the piano in the last game and went by “Jer.” Now he’s a bassist and goes by “Remy.” Same guy? Who can say? What about the guy at Blue Moose R&D who looks and talks like Dirk from Norwood, but calls himself Xavier? Identity is mutable in Off-Peak City, and there’s no such thing as continuity unless you look for it too hard.

That said, Tales from Off-Peak City Vol. 1 is more explicitly concerned with narrative and traditional worldbuilding than any of its predecessors. We get a much deeper exploration of the automata than we did in Norwood. (Automation and AI are almost as much a source of anxiety here as corporate ruthlessness.) Your quest to retrieve Caetano’s saxophone will eventually lead you into his apartment above the pizza shop, where he’s been keeping two automaton recreations of his wife and daughter and attempting to power them with, what else, pizza and energy drinks. You’ll find a map that points to a tremendous number of automata living in the mysterious face-shaped Building 9. You’ll learn that these automata are the work of Human Resources Horizons. You’ll learn more about the two organizations trying to take on HRH: the Circus, and your present employers–whose calling card is a black octagon. You’ll make connections everywhere.

All this narrative–and this modest incursion of gameplay–leaves less space for Tales to function as the kind of gallery space that its predecessors were. Sure, there’s a floor of an apartment building where one measure of Gershwin plays on a loop, and there’s sheet music for a part song by Josquin sitting in a drawer somewhere. But this element of Cosmo D’s work has been on a downward trajectory since the start. That’s for the best. It also makes this game a little harder to write about. Ultimately what fascinates me about Tales is much the same as what fascinates me about all of Cosmo D’s previous work: its sense of place. By the time you’re through, you’ve got the lay of the land. The politicians have forgotten this place, and the private sector has stepped in to take advantage. War is brewing. But there are still a few places the locals can go to feel part of something. The lounge in the basement of the pawn shop. The banks of the canal. The slice joint that everybody knows is going downhill.

It’s worth noting that nobody actually calls it “Off-Peak City.” From our perspective outside the story, the city is named after the first game that took place there. But I can imagine the nickname “Off-Peak City” catching on among the locals, like “City of Lights,” or City of Brotherly Love.” It’s what they’ll call the place once Marcus has taken total control of the transit system and the trains hardly come through anymore. Soon, there’ll be nobody left here. Off-Peak hours will apply to the whole metropolis. All this property will be snapped up by speculators and emptied out, a ghost town for the commuters to gaze upon as they zoom past on their prohibitively expensive train. Maybe they can open a pizza joint on the corner of Yam and July, for old times’ sake. It’ll be a hell of a lot better than Caetano’s and nobody will be able to afford it.

Betrayal at Club Low (2022)

There’s a moment during Marcus’s one scene in Tales from Off-Peak City Vol. 1 where somebody makes reference to a “next-level jazz-classical-electronic trio.” This tossed-off line has also turned out to be an approximate schema for Cosmo D’s first three commercial games. Norwood is his classical game. Tales is jazz. And Betrayal at Club Low is half RPG, half DJ set. It’s a game you can dance to.

Cosmo’s music is half the reason to play any of these games, but it seldom factors into the narrative the way you might expect from games that are explicitly about music. The scores of The Norwood Suite and Tales are non-diegetic: we don’t really know what Norwood’s music sounds like, or Caetano’s. Maybe we heard a little of DJ Bogart’s music in Norwood’s basement. But in this game the score could be DJ Chad Blueprint’s set coming through the walls of the club at any time. Granted, it’s odd that he always puts on a new record at the precise moment when you move into a new room.

Point is, this is the first of Cosmo D’s games where the sound and the subject are totally in concert. There have always been elements of jazz, classical and electronic music in these soundtracks, but even when the narrative focuses on one of the traditionally acoustic genres, there’s always a beat. This isn’t a circle that really needed to be squared, but Betrayal at Club Low finally provides a setting where a good beat is not just welcome but essential. Club Low is a high-stakes environment. The dancers waited a long time to get in, and they know what they like. Peril or glory awaits the brave DJ. Appropriately then, this game has a fail state.

For the first time in this body of work, there’s been a total change of genre. After four first-person adventure games (“walking simulators,” if we must), this is a straight-up third-person RPG with character stats and progression and health pools and “game over” endings. I expect that we’ll eventually see Betrayal as one of the early examples in a spate of post-Disco Elysium small-scale indie RPGs (Citizen Sleeper is another). But it also serves as the culmination of a trend in Cosmo D’s work that’s been underway for two games now: it makes the player character truly the center of attention, exerting a granularly personal influence on the world by rolling dice.

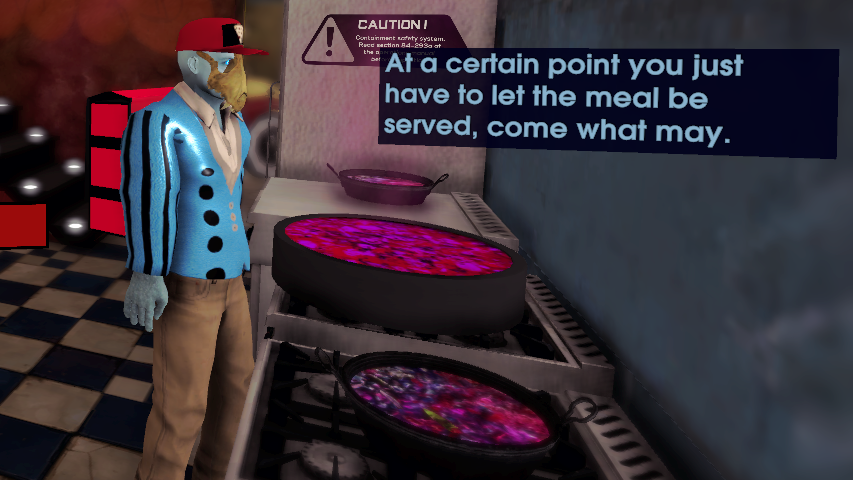

Relatedly, the other trend we’ve been tracing since Saturn V reaches a turning point here as well. We’ve been watching as the gallery-like sensibility of Cosmo D’s early games slowly gives way to narrative. Betrayal is the least gallery-like thing he’s ever made, and the most story-rich. There’s still plenty of fascinations and influences on display here, but they’ve been fully incorporated into the story, like flamingo meat into the fluorescent stew simmering in Club Low’s kitchen. Effectively, this means I’ve outlived my helpfulness as a tour guide.

Lest anybody misunderstand, there’s plenty in this story to remark on. We could note that Murial is now collaborating with the photographer from Tales who seemed so intent on driving her out of town. We could note that the player character is a wan automaton, confirming that whatever Murial’s aims, the Circus is not above using these things for their own ends. We could observe that we now know the automaton-filled Building 9 to be the headquarters of our mysterious former employers at the Octagon. Did you notice this is the first game where we weren’t dropped off by the last people we saw in the previous one? Or that DJ Bogart named his student Chad Blueprint his sole successor at Club Low one year before the release date of The Norwood Suite–did he know what he had coming to him?

This is all perfectly interesting, and I had a grand time with all of it as I was playing the game, which might be Cosmo D’s best. But concerns like this will never be the element of these games that lingers for me. It looks like there’s an Off-Peak City fan wiki in construction. Granted, people are free to engage with art however they like, but I’ve got mixed feelings about this. There is a part of me that thinks fan wikis enable the least useful, least interesting kind of engagement for a story like this. We may someday learn more about what the precise relationship is between the Circus and the Octagon, or about the origin of these automata, or whether Peter Norwood was ever a real person. But what would it accomplish to square away these surface-level ambiguities? Would it assist in understanding these games’ attitude towards art, or the wealth gap, or the deterioration of public services, or the importance of preserving heritage buildings, or the eternal tug of war between money and joy? I don’t think it would, and I’m much more interested in all of those concerns than I am in solving narrative riddles. If you’ve read this far and you’re disappointed that I didn’t do more of that sort of thing, well, sorry. The good news is that the Steam communities are full of it.

***

Let’s tie up a few loose threads. First: seven thousand words ago, I described myself as “a fellow traveler who shares Cosmo’s obsession with music, his love for the surreal, his irresistible impulse to put his obsessions on display, and perhaps his nagging sense that this impulse may be shallow.” The conflict that animates Off-Peak and makes it interesting is that it is, on one hand, an artist’s self-conscious attempt to draw attention to his own sophistication and eclecticism and, on the other, a satire of that exact tendency. It’s an exhibition that serves as its own art critic. Having now played Betrayal at Club Low and replayed Tales from Off-Peak City Vol. 1, I feel that their total success serves as an even more effective demonstration that the impulse to put one’s obsessions on display is indeed shallow. There’s definitely space for games to function like galleries. I’m thinking specifically of “Limits and Demonstrations,” the wonderful interlude between the first two acts of Kentucky Route Zero. “Limits and Demonstrations” puts you inside a virtual gallery space filled with artworks that would be impossible to exhibit in physical space. It’s Borges’ “reviews of impossible books” approach to literature, applied to visual art. I’d love to see more of that. But in Cosmo D’s case specifically, the more narrative-focused and less gallery-like these games have become, the more they feel like they’re about something other than themselves.

Second: since I started writing this piece, I’ve been eating a lot of pizza. I’ve switched my default from red wine to craft beer. I’ve been listening to Debussy, Milton Babbitt, funk-era Miles Davis, Burial, Four Tet: all artists that are suggested, if not referenced outright, by these games. It’s a complicated thing to grapple with. The notion that a personal aesthetic can be transformed into a brand and sold to others is an idea that troubles and haunts every one of these games, The Norwood Suite in particular. And yet, Cosmo D’s aesthetic is intensely seductive.

Finally: the closest pizza place to my childhood home was called Cosmo’s. It’s entirely possible that the first slice I ever ate was from that place.

Code Switch

Code Switch