I remember being twelve years old and witnessing the reception of Peter Gabriel’s Up, his first album in ten years, with some confusion. “Out of touch,” said Rolling Stone. “Dated” said the Guardian. I was a child out of time, born in 1990 but listening mostly to music from twenty years earlier than that. I was totally unaware of whether anything new I heard sounded current. I’d never heard the Nine Inch Nails albums and big beat music that Gabriel had clearly spent the 90s obsessing over. I didn’t know what anybody was talking about.

Up was the third record in Gabriel’s ongoing “delayed” period, in which he takes increasingly outlandish amounts of time to finish the records he starts. So took four years–an eternity in the ‘80s. Us took six, and spawned an anecdote that Sarah McLachlan still relates occasionally. Up took an unprecedented ten years to complete, including seven years of active recording. In 1997, Gabriel’s contemporary David Bowie released Earthling, an album inspired by industrial music and drum and bass. At the time, the NME described Bowie as “acutely conscious of his 50 venerable years,” and accused him of belated bandwagon jumping. Five years later, Peter Gabriel released Up.

Gabriel has always had the impulse to write about social movements, discourses, and subjects out of the news cycle (e.g. “Biko,” “Shaking the Tree,” “The Veil”). He has always had the impulse to introduce new sounds into his sonic palette (e.g. the Fairlight, drum machines). The defining condition of his last 30 years has been that he still attempts to do this, but he takes so long to release his work that the sounds and ideas are no longer contemporary by the time we get to hear them. The question becomes whether they’re still relevant, which is not the same thing.

Earlier this month, Gabriel finally released I/O, his first album of new material since Up. I’ve been aware of I/O since I was twelve, but it was perpetual vapourware: sidelined in favour of cover albums, legacy tours, and apparently “living.” It is extremely uncanny to hear it after all this time. With a bit more experience and cultural knowledge behind me, I find myself responding to it similarly to the way that some critics responded to Up in 2002.

I/O’s lead single “Panopticom” offers an inversion of Jeremy Bentham’s proposed prison design, where it isn’t the powerful who possess the all-seeing eye–it’s the people at the bottom, suddenly obtaining the means to hold the powerful to account. It’s an idea Gabriel has been fascinated with since he founded WITNESS, a charity that gave cameras to citizens of underprivileged countries for the purpose of filming human rights abuses. WITNESS vastly predates the role of phone cameras in BLM and the Arab Spring.

But does “Panopticom?” Given the timescale at play here, it may. And it certainly seems like it does–the song presents a futuristic vision of technology-assisted accountability that has already come to pass. Indeed, the promise of this moment has come and gone somewhat. We now live in a world where citizens’ unlimited ability to disseminate information has turned out to be a catastrophe, and not an emancipation. “Panopticom” is deeply, maybe even charmingly naive in the era of Elon Musk’s X. It is replete with the techno-utopianism of the early aughts. It even has a Web 1.0-style neologism for a title.

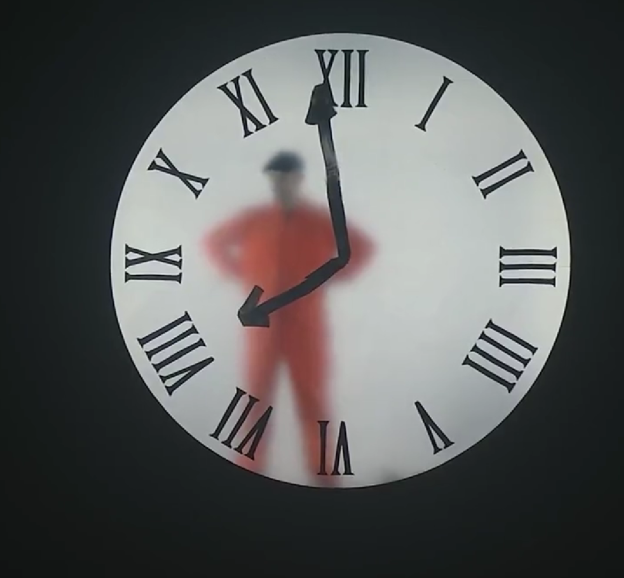

It’s a title that the neologism king Buckminster Fuller might have enjoyed, as might his devoted acolyte Stewart Brand. Brand is the definitive techno-utopian of his (and Gabriel’s) generation, and his influence is a quiet presence throughout I/O–especially on my favourite track, “Playing for Time.” It’s a simple ballad, expressing a mixture of anxiety and resignation about the passage of time. Brand shows his face in the final verse, which describes the Clock of the Long Now, a marvellous initiative from Brand’s Long Now Foundation (I/O co-producer Brian Eno is on the board of directors). The clock was conceived by Long Now co-founder Danny Hillis, to help humanity recognize the potential enormity of the future. It only exists as a prototype, but it will eventually be installed inside of a mountain in Texas. It will tick once a year. The century hand will advance once every hundred years. The clock will chime each new millennium, for 10,000 years.

Intentionally or not, “Playing for Time” is Peter Gabriel’s definitive statement on the last thirty years of his career. If “any moment that we bring to life will never fade away” as he says, then it doesn’t matter if you make an early-90s Nine Inch Nails album in 2002, because no moment, not even the present one, is any more or less valid than any other. And besides, 1992 and 2002 are infinitesimally close together. If it doesn’t seem that way, just listen to the silent clock in the mountain.

I/O has arrived into a dramatically different world than Up did. It has been received somewhat more positively in its first couple weeks, in spite of being–in my view–significantly less consistent. But we are not so quick to dismiss an artwork for being dated anymore. Now, we name and catalogue the distinct aesthetic trends of the past for easy reference, and we live in a static, patchwork culture of throwbacks and homage. Peter Gabriel was already unstuck in time when he released Up. Two decades later, the only difference is that we’ve joined him.

A recent newsletter promoting I/O described it as “an album of, and for, the here and now.” This is patently ridiculous. It’s worth noting that the album’s title refers not only to the expression “in, out,” but also to one of Jupiter’s moons. The album was a lunar phenomenon from the start: Gabriel released one song on every full moon of the last calendar year. His music exists on a cosmic timescale now, governed not by human trends but by the rotation of celestial bodies that will still be there when all that’s left of us are charred ruins and a stately old clock.