“How many things have I left unfinished? How many times have I pulled the brakes on a train of thought before arriving at a troubling certainty? And how long will it take me to finish reading this book?”

Matthew Parsons, September 2018

There are two ways to read Moby-Dick. “Quickly” is not one of them. No: if you make it from cover to cover in a sane and reasonable amount of time, your experience has been somehow wanting. I dare say the two ways to read Moby-Dick are better characterized as two viable defenses for why it is taking you so long to read it. I will call them the Ahab defense, and the Ishmael defense.

The Ahab defense asserts that the book is an obstacle to overcome. It is the defense mounted by those for whom the book has become their own “white whale.” Those who plead the Ahab defense may not even particularly enjoy reading Moby-Dick, but persist nonetheless because they feel they have to read it. The book has become a meaningless and insane compulsion: a task to be undertaken at the cost of their own time, mental health, and personal relationships.

This is not the defense I plan to assert. I will take the Ishmael defense. The Ishmael defense holds that nothing good ever comes from reaching an ending. Ishmael is the patron saint of amorphous and unpredictable middleness, only happy when he is literally and figuratively “out to sea.” From the moment I met him, I found this argument persuasive. And here we are five years later.

Fortunately, we still have a ways to go before we’ll have to contend with Moby-Dick’s ending. So let’s continue. Welcome back.

Chapter 42: The Whiteness of the Whale

This is one of Moby-Dick’s most famous chapters: something I anticipated the way you anticipate “to be, or not to be” in every new production of Hamlet. But “The Whiteness of the Whale” finds Ishmael in a very different mood from his other iconic digressions. This is the chapter where we watch his usual way of making an argument–marshaling an impossibly diverse and detailed range of examples–completely break down.

He begins by anticipating H.P. Lovecraft yet again, while trying to explain what specifically unsettles him about the whale:

“…there was another thought, or rather vague, nameless horror concerning him, which at times by its intensity completely overpowered all the rest; and yet so mystical and well nigh ineffable was it, that I almost despair of putting it in a comprehensible form. It was the whiteness of the whale that above all things appalled me.”

In his long-winded efforts to explain himself, Ishmael returns to the vein of horror fiction repeatedly, noting the whiteness in the visages of the dead, the matching colour of the shrouds in which they are traditionally wrapped, the whiteness of ghosts in the popular imagination, and the pale horse upon which Death proverbially rides.

He also touches somewhat awkwardly on race, noting that the global pre-eminence of the colour white “applies to the human race itself, giving the white man ideal mastership over every dusky tribe.” Neither Ishmael nor Melville actually subscribes to this sentiment, as pointed out throughout the rest of the book, and by Dr. Parker in the footnotes. Ishmael later invokes white colonialism in North America as a kind of fall from grace, implicitly filing white people alongside the polar bear, the great white shark, and all the other various bloodthirsty pale creatures he finds so uncanny. Perhaps this is too modern a reading for a book published in 1851, but I don’t really think so.

In any case, all of this quickly becomes unimportant. As you read this chapter you can actually feel Ishmael gradually giving up on his argument, nearly raising the “white flag” of surrender to an idea he can’t reckon with. But then he hits on something, almost by accident: as if a voice in his head has suddenly whispered a line from a half-forgotten nightmare.

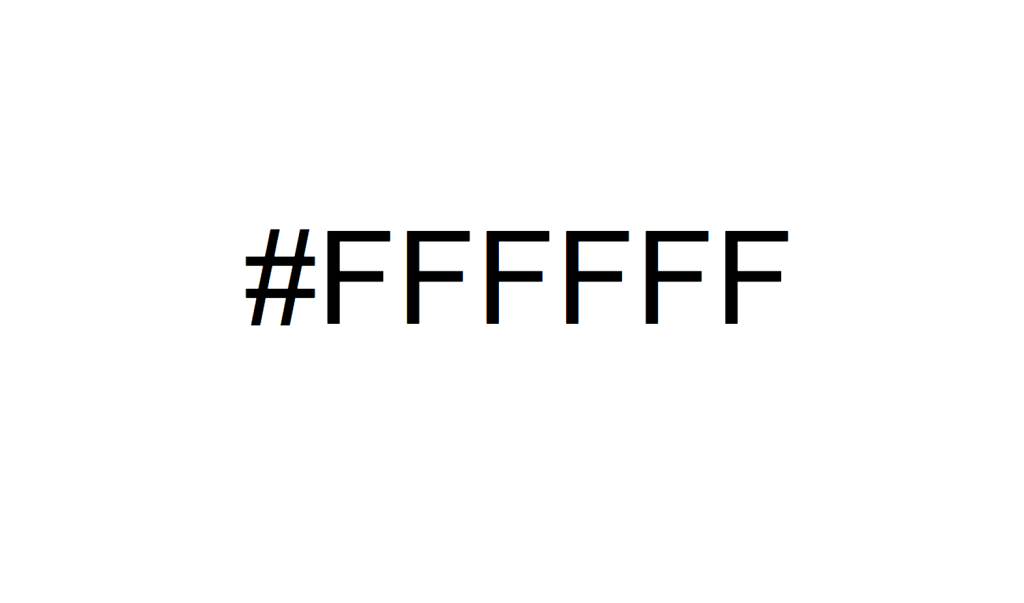

Ishmael recalls the idea that colour itself is a trick of the eye: that nothing is implicitly colourful and that colour only applies to a thing when it is observed. So, perhaps the universe is fundamentally colourless and blank, and light itself if not filtered through the subjectivity of human vision would render the whole world with the uncanny, impassive whiteness of the dead.

The terror of the white whale is simple, then. Its whiteness is a confession of some deeper, suspected truth about the universe: that all of its vibrancy and color is a lie, constructed by humans as a way to cope with the fundamental blankness of the world before them. This is the most insidious way that Ahab has gotten into Ishmael’s head. A few chapters ago, Ahab asserted that the whole world is a “pasteboard mask” obscuring the true nature of things, and that the white whale is an emissary from the bleak reality beyond.

Ishmael doesn’t invoke Ahab directly here. In fact, he comes closer to invoking Ahab’s opposite: his first mate, Starbuck. He refers to the blind instinct of a young colt, a “dumb brute”: the exact same words Starbuck used to refer to the whale. Starbuck would absolve the white whale of its violent tendencies because it acts on instinct: it lacks the willpower to act with real malice. But Ahab has recognized that “blindest instinct” is what the whole world is constructed from. And he cannot bear this. So he makes himself a golem of pure willpower, pure intention, and he lashes out at the universe’s indifferent violence.

Ishmael could never do the same: he’s a man of ideas, not a man of action. But something in Ahab’s philosophy has taken hold of him. Ahab introduced Ishmael to the prospect of a blank and colourless world. It’s an idea that can’t be unthought. That is the true horror of the whiteness of the whale.

Chapter 43: Hark!

It feels like ages since we’ve heard from the Pequod’s crew. Five years, at least. Actually it’s only been two chapters, which is not bad by Ishmael’s standards.

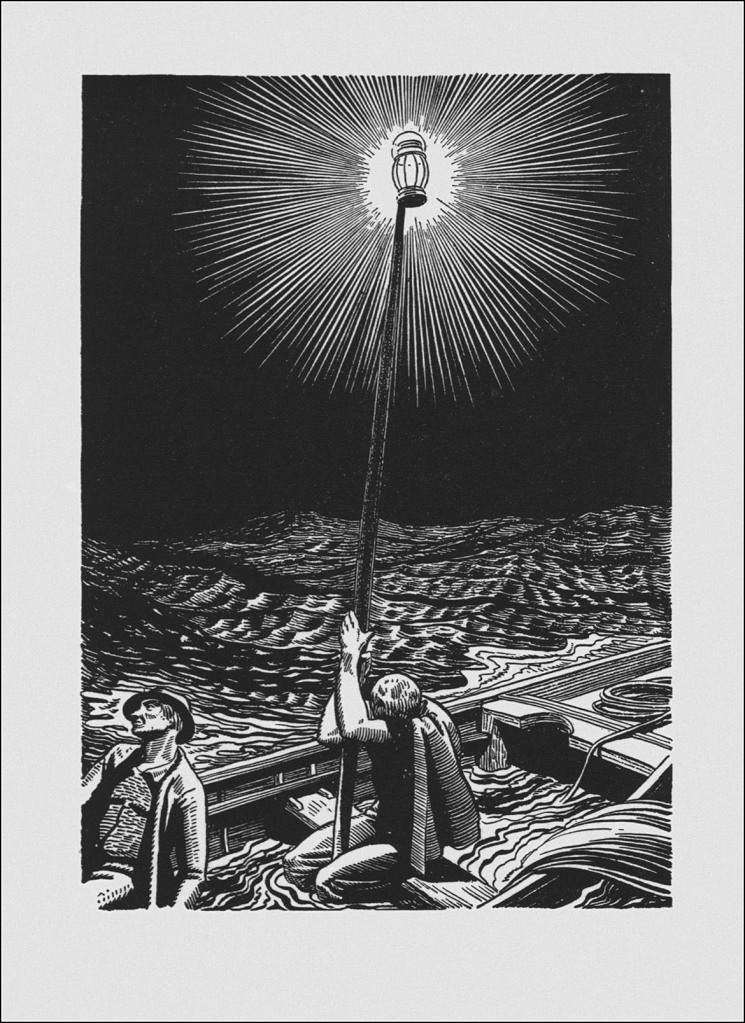

This brief scene is an exercise in suspense. Two sailors hear something odd at night–a cough, perhaps, from below decks. Previously, we heard from the prophet Elijah that Ahab had secreted something, or someone, aboard the ship under cover of darkness. Now it comes to mind again.

This is the kind of writing that subsidizes chapters like the previous one. Melville can afford to let Ishmael go on about his theories and anxieties, because he knows he can hook you into the story again in half a page or less.

Chapter 44: The Chart

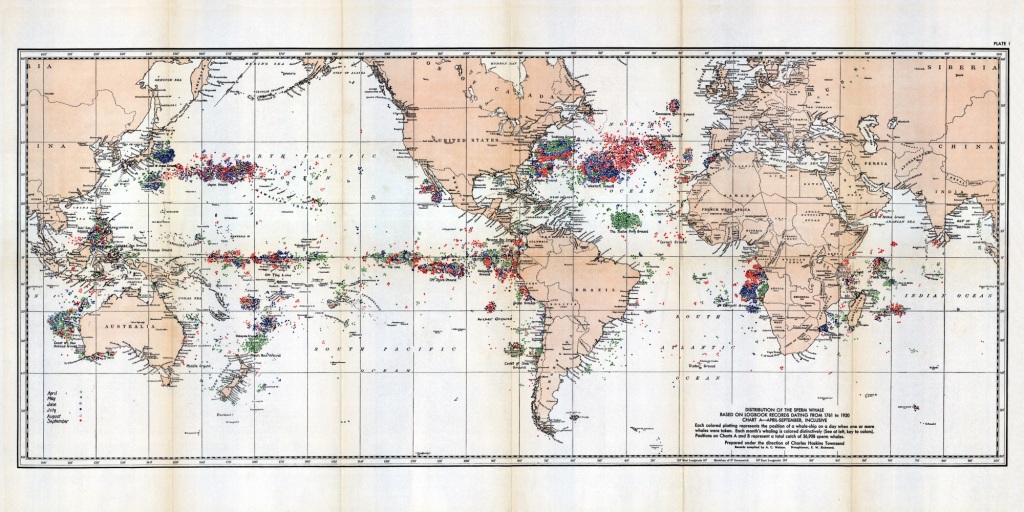

I expect there are readers who would prefer if all of Moby-Dick were written like this chapter, with Ishmael’s erudition folded neatly into the character drama. Most of the chapter concerns the surprising precision with which sperm whales travel, migrating predictably alongside their food sources. This makes their hunting easy for those who are willing to adequately obsess over their patterns.

But rather than frame this knowledge as a pure digression, Ishmael presents it as the sort of thing that a compulsive personality like Ahab would know. Ahab’s perverse rationality here reminds me of the insane narrator from “The Tell-Tale Heart”: “You should have seen how wisely I proceeded — with what caution — with what foresight — with what dissimulation I went to work!” Likewise, Ahab plots and plans, and mathematically adjusts his well-worn charts. But by night, we’re given the striking image of him sleeping with clenched fists, fingernails driving into his palms hard enough to draw blood.

Ishmael envisions Ahab split into two parts: the rational, thinking Ahab of the daytime–and the haunted willpower golem of the night. He returns to his grim realization from two chapters ago, describing this nocturnal Ahab as “a ray of living light… without an object to colour, and therefore a blankness in itself.” Neither Ishmael nor Melville are trying to be subtle in their analogies between Ahab and his quarry. What’s interesting is that Ahab conceives of himself as the opposing force to the white whale’s impartial violence, all the while animated by precisely the same sub-rational blind impulses. Is he indeed a creature of pure will, or a “dumb brute” himself? At this point I’m not sure, and neither is he, and neither is Ishmael, and probably neither is Melville.

Chapter 45: The Affidavit

Once again, Ishmael spends this whole chapter trying to lend credibility to his story. There’s something poignant about his outright insistence that he can once again simply make his point by citing examples. Only three chapters ago in “The Whiteness of the Whale,” we saw him try to do this very same thing, only to fail dismally and spiral into madness. Three chapters is how long it took for him to suppress this madness once again. I imagine he hopes we’ve forgotten. Probably he has.

In any case, the point he’s driving at here is that it isn’t so unlikely that a specific whaler could encounter a specific whale twice in one lifetime. Ishmael has seemingly witnessed this several times. Also, he’s asking us to believe that a whale is capable of acting with genuine vengeance, as opposed to simply self-defense. As part of his evidence, he cites the wreck of the Essex in 1820, the subject of the film The Heart of the Sea. The Essex was wrecked by a whale whose attacks “were calculated to do us the most injury,” and whose aspect “indicated resentment and fury.”

This is all part of Ishmael’s constant attempt to make us see the white whale from Ahab’s perspective. But he’s got another explicit goal as well: that we shouldn’t consider his story “a monstrous fable, or still worse and more detestable, a hideous and intolerable allegory.” I love this. It should be paraphrased in the comments of every YouTube video with “ENDING EXPLAINED” in the thumbnail.

Also, this may be the first time in the novel that Ishmael’s been funny on purpose: “…the Commodore set sail in this impregnable craft… But he was stopped on the way by a portly sperm whale, that begged a few moments’ confidential business with him.”

Chapter 46: Surmises

Here we have a whole short chapter dedicated to explaining that, however intent Ahab was on killing the white whale, he still had to placate his sailors’ need for money and diversion by operating a genuine whaling operation along the way. It finishes with the promise that soon we may actually witness some action. Maybe so, but we’ve been fooled before.

Chapter 47: The Mat-Maker

Fooled before, indeed, but not this time! From the moment this chapter starts, it’s clear there’s action coming. A placid reverie has taken over the ship, allowing Ishmael a few moments to reflect on the relationship between fate and free will–but only a few. This type of calm is clearly a storytelling device. It’s “the calm before the storm.” You can tell something’s about to happen just by the way that Melville situates Ishmael’s reflections at an actual point in time. If he intended to go on like this for a while, he’d just be talking to the reader about fate and free will directly, but here he’s reflecting on this while sitting beside Queequeg and weaving. While the story is happening.

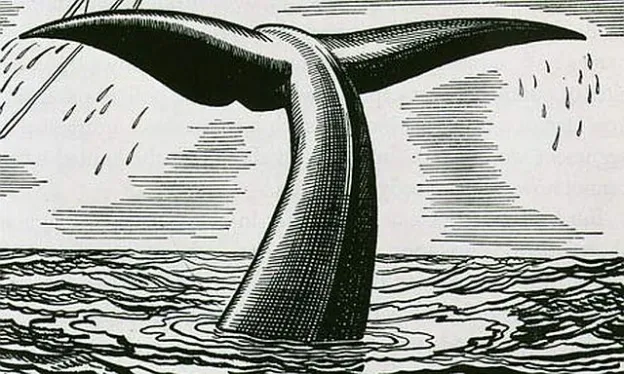

And when it happens, it happens. Tashtego sees a whale, and the Pequod jumpstarts into action. Moby-Dick the Long Essay is finally giving way to Moby-Dick the Adventure Story. And the suspense over the Mysterious Secret Below Decks is about to be relieved.

Chapter 48: The First Lowering

There’s a moment halfway through this chapter that feels like a fulcrum point: standing aboard a boat pursuing a whale through the sea, the harpooner Tashtego spies a flicker of movement below: “Down, down all, and give way!–there they are!” It took nearly eight-five thousand words to get here, but WE’RE HUNTING WHALES, BABY

This is the first truly action-packed chapter in the book. Even so, the thrill of it lies mainly in watching these characters we’ve come to know so well behaving exactly as you’d expect them to behave under pressure. Stubb is loud and garrulous, Starbuck quiet and a little scary. And Flask, when we catch a glimpse of him, is careless–risking life and limb in pursuit of his ambition. He stands on his massive harpooneer’s shoulders to see across the water: action comedy worthy of George Miller.

As for the Mysterious Secret Below Decks, the rattling, coughing shadows seen and heard at various points throughout the story are five expert whalers from Manila. Suddenly, we see them released from their quarters to join Captain Ahab himself on one of the smaller boats lowered from the ship for the hunt.

The crew and officers regard these men with total shock and astonishment. Perhaps we can even understand their racism towards the newcomers, given what a betrayal of trust this is on Ahab’s part. To the crew, the new arrivals could have simply arrived on the Pequod suddenly from hell. Even Ahab’s first mate Starbuck is taken by surprise. Leave it to second mate Stubb to find a way to rouse his men to action in this challenging moment: “Never mind the brimstone–devils are good fellows enough.”

Ahab speeds toward his destiny as if on rails, propelled by his team of sudden demons. We’ve heard a sample from each of Ahab’s mates, indicating how they speak to their men. But Ishmael declines to reproduce the words Ahab speaks at this moment. No doubt they are devilish words, unhearable by delicate landsmen and good Christians.

By this point, the reader may well feel like they’ve picked up another book entirely from the one they’ve been reading all these years. It’s as if a painting turned into a movie. Appropriately, Melville caps off his first chapter of genuine action by zooming out his camera from the character details we’ve seen so far:

“It was a sight full of quick wonder and awe! The vast swells of the omnipotent sea; the surging, hollow roar they made, as they rolled along the eight gunwales, like gigantic bowls in a boundless bowling-green; the brief suspended agony of the boat, as it would tip for an instant on the knife-like edge of the sharper waves, that almost seemed threatening to cut it in two; the sudden profound dip into the watery glens and hollows; the keen spurrings and goadings to gain the top of the opposite hill; the headlong, sled-like slide down its other side;—all these, with the cries of the headsmen and harpooneers, and the shuddering gasps of the oarsmen, with the wondrous sight of the ivory Pequod bearing down upon her boats with outstretched sails, like a wild hen after her screaming brood;—all this was thrilling.”

Pure kino.

Anyway, Ishmael finds himself on the unlucky boat at the end of this. He and Starbuck are separated from the others by a squall, and a whale surfaces directly underneath their boat. YOU WANTED WHALES, WELL BUDDY YOU GOT ‘EM

Chapter 49: The Hyena

Surely we can afford our narrator a few moments of light philosophy, given how much action he just managed to get through. We know it’s hard for him. Give the man a break. Certain experiences, Ishmael tells us, are so hilariously grim that they can cause a person to stop taking his misfortunes so seriously. He must simply join the cosmic hyena in its laughter. This hyena doesn’t appear in Ishmael’s narration. It’s only implied by the chapter title. But I expect this hyena will be laughing throughout the rest of the book.

Anyway. Once he gets back to the ship, Ishmael’s colleagues reassure him that this harrowing misadventure he’s been through is just par for the course in the whaling industry. No reason to get worked up about it. You only nearly died. Ishmael recruits Queequeg as the executor of his will, and suddenly feels much more at ease.

Chapter 50, Ahab’s Boat and Crew–Fedallah

This chapter concludes with a racist passage implying that Fedallah, the newly-arrived Filipino harpooneer, is some sort of devil-spawn. Reading against the grain, these troublesome moments are the points when Moby-Dick truly earns its reputation as the Great American Novel. Elsewhere, it’s just a Great Novel.

It’s been two chapters since the shock reveal of five hitherto unseen crew members aboard the Pequod. Now we learn why they’re here: it’s unusual for a captain to actually participate in the whale hunt himself, especially not a disabled one. The Pequod’s owners would have never allowed this, so Ahab secretly arranged for his own boat crew to be shepherded on board by night and kept below decks until the moment of truth.

Flask argues that Ahab ought to quit while he’s ahead. At least he’s got one knee left. Stubb counters: “I don’t know that, my little man; I never yet saw him kneel.” I wonder if we ever will.

To be continued.