ABBA Gold is the apex of the compilation. It hails from a bygone era—the pre-streaming era—before all the hits and misses were in one place together by default. Once, collections like this were produced to satiate a legendary beast called the Casual Fan, who wanted access to the hits and didn’t want to be burdened with the deep cuts.

This is what ABBA Gold was designed to be. But, oh, it is so much more. It is the definitive ABBA experience: the central canonical text. It is a piecemeal masterpiece; it is ABBA’s best release. It is one of a small handful of the greatest capital-P Pop albums ever contrived, and they are all contrived.

Granted, this is at least partly because ABBA were not an album band.* For example, the album that spawned two of the greatest pop singles of all time, “S.O.S.” and “Mamma Mia,” contains by my estimate: zero other tracks that are even good—let alone timeless. There are two kinds of album bands: those that are ruthlessly consistent (e.g. the Beatles) and those that are pleasantly weird even on their off days (e.g. Neil Young). ABBA are neither. You don’t want to listen to their bad songs. Don’t listen to “Rock Me.” Don’t do it.

Don’t.

The other reason ABBA Gold is a special case among compilations is even simpler: ubiquity. Since its minimal, black and gold art hit Walmart shelves in 1992, it has become the defining image associated with the band. In the quarter century since its release, ABBA Gold has entered into the public consciousness not as an afterthought, but as an ABBA album. The ABBA album. Notwithstanding the one that’s almost actually called that.

So, while the Red and Blue albums and Decade remain treasured items in many record collections, they are fundamentally less essential than ABBA Gold. That’s not to say that it’s better than those albums. There are a handful of weak tracks on ABBA Gold that could stand to be replaced with more minor hits, or some of the stronger album cuts.

But in the end, those weak tracks barely register. Nobody’s best songs are more satisfying, cathartic, and flawless than ABBA’s. This album’s top-tier tracks are hewn from marble. They are natural phenomena that ABBA merely discovered. Listen to any other ABBA album and you’ll note that they’re contemporaries of the Bee Gees. Listen to ABBA Gold, and you’ll realize that they’re peers of Mendelssohn and Ellington.

To be clear: it is 2019. You can have as many or as few ABBA songs on your phone as you want. You can make your own ABBA compilation. You can let one of Apple’s expert curators or Spotify’s algorithm do it for you. Compilation albums are an obsolete format. But not this one. Because it’s ABBA Fucking Gold.

Below is my detailed appraisal of this genuine monument to human brilliance, in the only format possible on the internet: a ranked list of songs.

19: Does Your Mother Know

The biggest duffer on the disc by a mile. It’s almost a sure bet in the ABBA corpus that a male lead vocal indicates a bad song, and probably also a creepy one, c.f. “Man in the Middle.” I don’t like songs about adult men pursuing underage women *John Mulaney voice* AND YOU MAY QUOTE ME ON THAT. To be fair, that’s less true of “Does Your Mother Know” than “Man in the Middle.” The narrator in this one has some scruples, but he’s still a condescending jackass.

The biggest duffer on the disc by a mile. It’s almost a sure bet in the ABBA corpus that a male lead vocal indicates a bad song, and probably also a creepy one, c.f. “Man in the Middle.” I don’t like songs about adult men pursuing underage women *John Mulaney voice* AND YOU MAY QUOTE ME ON THAT. To be fair, that’s less true of “Does Your Mother Know” than “Man in the Middle.” The narrator in this one has some scruples, but he’s still a condescending jackass.

If we must have a song about a troublesome, unexamined power dynamic between an older man and a younger woman, couldn’t it at least be “When I Kissed the Teacher?” That one’s got better hooks.

18: Thank You for the Music

A music hall number, but the treacly, sentimental kind rather than the fun ironic kind. I hear you ask: how can you be complaining about sentimentality… in an ABBA song??? It’s a valid point.

A music hall number, but the treacly, sentimental kind rather than the fun ironic kind. I hear you ask: how can you be complaining about sentimentality… in an ABBA song??? It’s a valid point.

Here’s the thing. I think there is a time for sentimentality, but that time is when you are indulging yourself in misery and despair. “Thank You for the Music” is hardly the only sentimental song on this list, but the good ones are despondent love dirges. Those of us with a tendency to wallow in self-pity might see ourselves reflected in songs like “The Winner Takes it All.” Their sentimentality is the point: they exist in a world absent of rationality, like we all do sometimes.

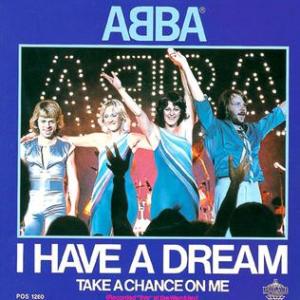

But anybody who sees themselves reflected in the trite platitudes of “Thank You for the Music” must be an empty, grinning skin balloon. If you’re going to compose a panegyric to the power of music, at least have the courtesy to couch it in mythic language. At least have the courtesy to write the Hymn to St. Cecilia.

17: I Have a Dream

Charitably, you could read it as a song in the tradition of “Whistle While You Work” or “I Get Along Without You Very Well,” in which the singer is trying as hard as they can to ignore something unpleasant. But “I Have a Dream” doesn’t offer any specifics about what the unpleasant thing is. Moreover, the cheery music makes it seem like the singer’s strategy is actually working. Where’s the tension in that?

Charitably, you could read it as a song in the tradition of “Whistle While You Work” or “I Get Along Without You Very Well,” in which the singer is trying as hard as they can to ignore something unpleasant. But “I Have a Dream” doesn’t offer any specifics about what the unpleasant thing is. Moreover, the cheery music makes it seem like the singer’s strategy is actually working. Where’s the tension in that?

16: Chiquitita

Presumably it made a ton of money for UNICEF. But it’s basically “Blackbird” with a less memorable melody and the panpipes from “El Condor Pasa” grafted on. It is the song on ABBA Gold about which I have essentially no opinion.

Presumably it made a ton of money for UNICEF. But it’s basically “Blackbird” with a less memorable melody and the panpipes from “El Condor Pasa” grafted on. It is the song on ABBA Gold about which I have essentially no opinion.

15: The Name of the Game

It’s weird to me that the compilers of this album shunted so much of the weaker material onto side four. If not for the promise of “Waterloo” to finish, you might be inclined to switch off at the three-quarter mark. I often do.

It’s weird to me that the compilers of this album shunted so much of the weaker material onto side four. If not for the promise of “Waterloo” to finish, you might be inclined to switch off at the three-quarter mark. I often do.

“The Name of the Game” has some nice harmonies in the chorus, but it bides its time in the verses. Plus, it is a dreadful illustration of what I call “the ABBA problem.” The ABBA problem is the fact that sometimes ABBA’s lyrics take on a disturbing new dimension when you consider that they are written by two men, for their wives to sing. (See: “I’m a Marionette” for the most distressing example.) Lines like “I think I can see in your face there’s a lot you can teach me” and “I’m a bashful child, beginning to grow” are deeply icky when you think of Benny or Björn being like “yes, I would like to hear my wife sing that.” Ugh.

14: One of Us

ABBA excelled at writing songs for those of us who do not experience emotional numbness, but rather a surfeit of negative emotion. This song is right in their comfort zone, which is horrible anguish painted in broad strokes of luminous colour. So basically—adolescent anguish. There are subtle gradations of maturity in ABBA’s heartbreak songs—songs of innocence and songs of experience. This one’s the former. And that’s fine. We should all be willing to admit that pop music is actually for kids.

ABBA excelled at writing songs for those of us who do not experience emotional numbness, but rather a surfeit of negative emotion. This song is right in their comfort zone, which is horrible anguish painted in broad strokes of luminous colour. So basically—adolescent anguish. There are subtle gradations of maturity in ABBA’s heartbreak songs—songs of innocence and songs of experience. This one’s the former. And that’s fine. We should all be willing to admit that pop music is actually for kids.

“One of Us” is an outlier on ABBA’s weatherbeaten final LP. Nestled among paranoid Soviet disco and divorce anthems, this one’s a teen movie reenactment, where a young woman cries in bed “feeling stupid, feeling small.” Its power comes from the fact that most of us are only one bad experience and a few drinks away from being our teenage selves again.

13: Fernando

ABBA’s storytelling side isn’t well represented on ABBA Gold. And fair enough—they do usually traffic in relatable generalities, like most pop bands. But occasionally, a Johnny Cash/Bruce Springsteen/Kate Bush impulse surfaces and they get into character. It happens in their mini-musical The Girl With the Golden Hair. It happens in “The Visitors.” (If there’s one track that’s not on ABBA Gold that should be, it’s “The Visitors.”) And most profitably, it happens in “Fernando”: a tale of two comrades-in-arms.

ABBA’s storytelling side isn’t well represented on ABBA Gold. And fair enough—they do usually traffic in relatable generalities, like most pop bands. But occasionally, a Johnny Cash/Bruce Springsteen/Kate Bush impulse surfaces and they get into character. It happens in their mini-musical The Girl With the Golden Hair. It happens in “The Visitors.” (If there’s one track that’s not on ABBA Gold that should be, it’s “The Visitors.”) And most profitably, it happens in “Fernando”: a tale of two comrades-in-arms.

It’s a slow burn to that magnificent chorus, but along the way, we get a pair of glorious, serpentine verses, packing in extra lines and syllables so gracefully that you never notice how weirdly shaped the musical phrases are unless you go looking. When the third verse comes around, you realize why these two soldiers are singing so wistfully about such a frightening experience: they’re old and grey, and this story has receded into a sepia-toned fantasy for them.

“Fernando” is a barely imperfect pop hit. The arrangement lets it down (there’s that pan flute again), and a couple lines don’t stick the landing (“the roar of guns and cannons almost made me cry”). But the chorus is iconic, the story connects, and hey—it’s the ABBA song that forced Brian Eno to admit he was a fan, so there must be something to it.

I suspect this might be the one people yell at me for not placing higher. But honestly, it’s nothing but bangers from here on out. “Fernando” is the shit. Here are twelve songs that are even better.

12: Waterloo

ABBA songs generally sound either dated or timeless. There isn’t really a lot of middle ground—you’re either rolling your eyes at the audio equivalent of dancing lamé, or you’re marvelling at how these songs could still be hits today. They are either painfully “70s/80s,” or they are ethereally detached from time.

ABBA songs generally sound either dated or timeless. There isn’t really a lot of middle ground—you’re either rolling your eyes at the audio equivalent of dancing lamé, or you’re marvelling at how these songs could still be hits today. They are either painfully “70s/80s,” or they are ethereally detached from time.

Odd then, that ABBA’s breakout hit is a throwback to about 1963. Its infectious groove is what music school kids call a “shuffle feel”: a galloping “dut… duh dut… duh dut” that permeates the early Beatles records like a whiff of mothballs and dissipates gradually after Revolver. It’s a strange fish for 1974. It’s a strange fish on ABBA Gold.

“Waterloo” presages the sensation of listening to later ABBA hits: on the surface, it’s a blast of pure musical euphoria. But pick at that surface for a couple minutes and it reveals something… off. The English is stilted. That shuffle beat is a decade out of phase. And the premise is flat-out obtuse. I highly doubt that any person in the world has ever realized they were falling in love and immediately jumped to the battle of Waterloo as an apt metaphor.

None of this matters, of course. “Waterloo” is a rave-up of grand proportions. It’s the song where ABBA found their core identity: completely human and a little bit alien at the same time.

11: S.O.S.

It’s all about those synth arpeggios. They’re more than a cool effect—they hold the song together. This is one of ABBA’s secret weapons: a seamless transition from one part of a song to another.

It’s all about those synth arpeggios. They’re more than a cool effect—they hold the song together. This is one of ABBA’s secret weapons: a seamless transition from one part of a song to another.

The arpeggios are doing more work than simply changing the key. (“S.O.S.” uses the classic structure of verses in a minor key, chorus in major. It’s a key change we’re used to hearing. There’s no need for any clever business to mask it.) They’re changing the whole mood of the song. It’s pretty desolate at the start, but the chorus is a banger. You need some kinetic energy to get from one to the other without it feeling like a smash cut. Those arpeggios are an efficient, elegant way to do it. They hold a song together that might otherwise feel like two separate, excellent but incompatible songs.

I’m not convinced that either section of “S.O.S.” measures up to all the later hits. But the ingenuity of its construction makes it better than the sum of its parts.

10: Voulez-Vous

Quick! What’s your favourite ABBA riff? This is a question you have probably never been asked. (If so, was it me who asked you? Doesn’t count.)

Quick! What’s your favourite ABBA riff? This is a question you have probably never been asked. (If so, was it me who asked you? Doesn’t count.)

Killer Riffs are the province of a different kind of band from ABBA. The farther you get from Delta blues, and the closer to Tin Pan Alley, the less likely you are to write a Killer Riff. This is one of the few ways in which the Rolling Stones outpace the Beatles. ABBA falls squarely in the Tin Pan Alley camp. And yet, here on “Voulez-Vous,” we undeniably have a Killer Riff. Most of ABBA’s attempts at disco sound faintly awkward, but the rapid-fire 21-note riff that launches “Voulez-Vous” provides so much momentum that it almost doesn’t matter what comes after.

And what comes after is pretty great, anyway: the horns and “a-has” in the chorus, the rising drama of “and here we go again, we know the start, we know the end,” the juxtaposition of the French title with the colloquial “ain’t.” It’s an uncomplicated delight.

9: Money, Money Money

Speaking of Tin Pan Alley, here’s a straight up showtune. To my ears, “Money, Money, Money” has one of ABBA’s two or three best arrangements—certainly the most elaborate one on this collection. The song itself is a rueful drama with a fabulous, vampy vocal from a careworn Frida Lyngstad. But it’s the piano and mallet percussion that brings it to life. The restlessly repeating honky-tonk pattern at the start of the verse underscores the anxiety in the lyric. The plunk-plunk-plunk piano line before the chorus, which switches the emphasis pattern halfway through, makes it sound like ABBA called up Irving Berlin for a co-write.

Speaking of Tin Pan Alley, here’s a straight up showtune. To my ears, “Money, Money, Money” has one of ABBA’s two or three best arrangements—certainly the most elaborate one on this collection. The song itself is a rueful drama with a fabulous, vampy vocal from a careworn Frida Lyngstad. But it’s the piano and mallet percussion that brings it to life. The restlessly repeating honky-tonk pattern at the start of the verse underscores the anxiety in the lyric. The plunk-plunk-plunk piano line before the chorus, which switches the emphasis pattern halfway through, makes it sound like ABBA called up Irving Berlin for a co-write.

(Note: I’d originally written there that ABBA “exhumed” Irving Berlin for a co-write, but he was in fact alive at the time and 88 years old. He died in 1989 at 101. Irving Berlin outlived ABBA by seven years.)

8: The Winner Takes it All

Misery. Destitution. Dolor. Regret. Classic ABBA.

Misery. Destitution. Dolor. Regret. Classic ABBA.

“Inside every cynical person is a disappointed idealist,” George Carlin used to say. Swap out “idealist” for “romantic,” and you’ve got “The Winner Takes it All.” This narrator expresses herself with surging melodies and rising drama—the language of a romantic. But the sentiment she’s expressing is boilerplate cynicism. Love is a game, she’s learned. This is a heartbreak ballad sung by a person who’s either never heard a heartbreak ballad before, or who’s never had any reason to trust them. It is a loss of innocence made manifest as music.

It builds and builds, expanding outwards from a lonesome soul at the piano to a whole disco universe consisting solely of one woman’s pain. A sadder and a wiser woman she’ll rise the morrow morn and pretty soon she might even give up on lines like “the gods may throw a dice, their minds as cold as ice.”

“The Winner Takes it All” is too much, stated too bluntly. No matter; it’ll still break your heart after a couple drinks.

7: Knowing Me, Knowing You

It might be the ABBA song where the pieces fit together the best. And there are a lot of pieces. Six chirpy chords off the top evaporate into a dramatic, torchy minor key verse. The chorus starts with a title drop and chunky guitar chords. Seconds later, we’ve gotten to “breaking up is never easy,” and the song’s finally made it to its major key home. (Like Schubert, ABBA gets sadder when they’re in a major key.) The chorus gives way to the riff half a measure before you expect it to. A pair of electric guitars wails at each other while one of them dies of consumption, and we’re back into the verse.

It might be the ABBA song where the pieces fit together the best. And there are a lot of pieces. Six chirpy chords off the top evaporate into a dramatic, torchy minor key verse. The chorus starts with a title drop and chunky guitar chords. Seconds later, we’ve gotten to “breaking up is never easy,” and the song’s finally made it to its major key home. (Like Schubert, ABBA gets sadder when they’re in a major key.) The chorus gives way to the riff half a measure before you expect it to. A pair of electric guitars wails at each other while one of them dies of consumption, and we’re back into the verse.

Although it comes from four years earlier, “Knowing Me, Knowing You” is as much a song of experience as “One of Us” is a song of innocence. It’s there in the title, twice—the disappointment explicitly comes from the condition of knowing. It is the tragedy of inevitability in retrospect.

That whispering in the second verse is ridiculous, though.

6: Lay All Your Love On Me

Anxiety disco in a gothic cathedral. Imagine those opening synth chords played on a gigantic church organ. “Lay All Your Love On Me” is a perversely liturgical-sounding song. It is borderline blasphemous; daemonic.

Anxiety disco in a gothic cathedral. Imagine those opening synth chords played on a gigantic church organ. “Lay All Your Love On Me” is a perversely liturgical-sounding song. It is borderline blasphemous; daemonic.

But who is the demon? Is it the potentially philandering lover the narrator is singing about? Is she truly paranoid, or is our narrator a victim of gaslighting? Or maybe the narrator is the demon. Maybe she’s Kathy Bates in Misery, winding up to preemptively break some ankles.

Either way, this song is pure evil.

5: Super Trouper

The first few times I listened to “Super Trouper,” I thought it was about the transformative power of performance—how the thankless grind of touring evaporates into ecstasy when the narrator goes onstage. I was hearing what I wanted to hear. Those of us who are not pop stars would like to think it’s a rewarding life; that the artists we choose as vessels for our own dreams are in fact “living the dream.”

The first few times I listened to “Super Trouper,” I thought it was about the transformative power of performance—how the thankless grind of touring evaporates into ecstasy when the narrator goes onstage. I was hearing what I wanted to hear. Those of us who are not pop stars would like to think it’s a rewarding life; that the artists we choose as vessels for our own dreams are in fact “living the dream.”

But “Super Trouper” tells the opposite story: that performance has become meaningless to the performer. No line in ABBA rings quite as hollow as when the narrator refers to her audience as “twenty thousand of [her] friends.” Still, it’s one of ABBA’s most affirming songs, specifically because it emphasizes how civilian life offers deeper rewards than stardom. It isn’t the stage lights that dispel the darkness for the singer, it’s the comparatively mundane experience of a functional human relationship.

Mind you—for ABBA, functional relationships proved to be more difficult than topping the charts.

4: Dancing Queen

I am not the first person to hear a hint of melancholy in “Dancing Queen.” I could explain it with junk music theory. (“It’s done with suspensions… it’s about the way chords resolve…”) But the melancholy of “Dancing Queen” is really a matter of perspective.

I am not the first person to hear a hint of melancholy in “Dancing Queen.” I could explain it with junk music theory. (“It’s done with suspensions… it’s about the way chords resolve…”) But the melancholy of “Dancing Queen” is really a matter of perspective.

“You are the dancing queen,” the lyric goes. An incurable optimist might hear this as an inclusive statement, bringing the listener into the show. (“You are the dancing queen! And you are the dancing queen! And you are the dancing queen! EVERYBODY IS THE DANCING QUEEN!!!”) But we’re not used to hearing pop songs sung in the second person—most of the time, we’re only explicitly involved in a pop song when the singer is entreating us to do something in the imperative: “Shake it up baby, now/twist and shout.”

So, when we hear “you” in “Dancing Queen,” instead of assuming that we are the protagonist of the song, we infer the presence of a narrator, talking to a specific person. And if there’s a narrator, with an inner life all of their own, there’s an unspoken line after the title drop: “You are the dancing queen… and I am not.”

Sure, it’s got a chorus like a box of neon crayons. But “Dancing Queen” is sung from the darkest corner of a brightly-lit room.

3: Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight)

ABBA’s disco apotheosis. Leave it to them to write a song designed for dancing, which also explicitly points out the dark side of why people go out at night. It’s the same reason Springsteen pulled up in front of Mary’s porch, entreating her to come along for a joyride: “I just can’t face myself alone again.” It’s not just about love, or even sex. It’s about the tragedy that we are genetically predisposed to fear loneliness, but we are not universally adapted to avoid it. It’s about how hard we have work to escape the pull of the abyss.

ABBA’s disco apotheosis. Leave it to them to write a song designed for dancing, which also explicitly points out the dark side of why people go out at night. It’s the same reason Springsteen pulled up in front of Mary’s porch, entreating her to come along for a joyride: “I just can’t face myself alone again.” It’s not just about love, or even sex. It’s about the tragedy that we are genetically predisposed to fear loneliness, but we are not universally adapted to avoid it. It’s about how hard we have work to escape the pull of the abyss.

The chorus is iconic, but as with so many ABBA songs (“Super Trouper,” “S.O.S.”) the crystallizing moment comes immediately before the chorus. When Fältskog sings “no one to hear my prayer,” drawing out the last word for two measures, she hangs on the seventh of the chord far past the point when you expect it to resolve upwards. She holds the song in an extended moment of almost. Her prayer never reaches its destination. The crowd dances on as all her efforts come to nothing.

2: Take a Chance On Me

I could go on forever about how every great ABBA song is a dark psychodrama dressed up in pastel colours. But really, everybody already knows that. The real reason ABBA songs are so good is that their hooks are a hit of pure dopamine, even when melancholy does register.

I could go on forever about how every great ABBA song is a dark psychodrama dressed up in pastel colours. But really, everybody already knows that. The real reason ABBA songs are so good is that their hooks are a hit of pure dopamine, even when melancholy does register.

“Take a Chance On Me” is on one level a fairly pathetic song about a person so besotted that they’ll passively wait in line for a relationship that will probably never happen. But the groove of the “Take a chance, take a chance, take a take a chance chance” backing vocals is so undeniable that you can’t help but feel it might work out after all. The arrangement is packed full of audio bonbons like the pulsing synths on “It’s magic” and the incongruous country guitar lick after “I can’t let go, ‘cause I love you so.” It’s fun. It’s just fun.

The most telling moments in the song are the choruses where Fältskog and Lyngstad sing “bah bah bah bah BAH” over the first couple lines, in spite of the fact that there are perfectly serviceable lyrics available for that bit of the chorus. You can hear them right at the start of the song. Those nonsense syllables aren’t filling space. They just feel right. That one moment, maybe more than any other, demonstrates why ABBA are the best pop group ever.

1: Mamma Mia

There are more cathartic ABBA songs than “Mamma Mia.” There are more expressive and sincere ABBA songs too, that reflect listeners back at themselves more uncannily. But, look. If that’s all that ABBA songs were, they wouldn’t stand up to the kind of compulsive repeat listening that they do. The real reason that ABBA is a great band has nothing to do with their ability to articulate specific human emotions. Hundreds of bands can do that. What makes ABBA special is that they write music that feels like it’s always existed. I can’t explain it any better than that. The first time you hear a great ABBA song, it’s like becoming aware of a natural condition of the human mind that you hadn’t previously noticed, but which was always there. “Earworm” doesn’t begin to describe it. An ABBA song can become a part of you. That’s never been truer than in the case of “Mamma Mia,” because “Mamma Mia” is almost elementally simple—it is built with the smallest possible building blocks.

There are more cathartic ABBA songs than “Mamma Mia.” There are more expressive and sincere ABBA songs too, that reflect listeners back at themselves more uncannily. But, look. If that’s all that ABBA songs were, they wouldn’t stand up to the kind of compulsive repeat listening that they do. The real reason that ABBA is a great band has nothing to do with their ability to articulate specific human emotions. Hundreds of bands can do that. What makes ABBA special is that they write music that feels like it’s always existed. I can’t explain it any better than that. The first time you hear a great ABBA song, it’s like becoming aware of a natural condition of the human mind that you hadn’t previously noticed, but which was always there. “Earworm” doesn’t begin to describe it. An ABBA song can become a part of you. That’s never been truer than in the case of “Mamma Mia,” because “Mamma Mia” is almost elementally simple—it is built with the smallest possible building blocks.

Next time you listen to “Mamma Mia” (do it now), note how much of it is made up of sequences of two alternating notes. Tick TOCK tick TOCK tick TOCK tick TOCK in the intro. MAM-ma MI-a at the start of the chorus. Almost everything the xylophone does fits that pattern. It’s an unsettling pattern—low-level anxiety rendered in music. Take the opening. Each of the first seven notes is either a statement or a question. “This. What? This. What? This. What? This.” Then the harmony changes and the questions become even more insistent. “What!?! This. What!?! This. What!?! This. What!?! This.” No answer is ever final enough to prevent another question. This music is unstable on a granular level. It’s the musical equivalent of this guy, except he never regains his balance. That’s part of what makes “Mamma Mia” so addictive: it is based on maybe the simplest riff possible, but it’s a riff with narrative perpetual motion baked into it. It can never be certain, can never sit still.

But of course, it’s not enough. We need a point of contrast. Enter the lead guitar, with a line that surges upward with all the decisiveness that the two-note riff lacks… and then slumps down again. Most of the melodies in the verses follow the same pattern: surging upward (“I’ve been cheated by you…”), and slumping back down (“…since I don’t know when”).

So: we’ve got a restless two-note riff that cycles endlessly, and a contrasting melodic pattern that charges forward only to lose its nerve and double back. This, in a song about a woman who is caught in a destructive cycle with her significant other (“here we go again”), who decides to finally break that cycle (“so I’ve made up my mind it must come to an end”), only to realize that she can’t (“one more look and I forget everything”).

Beethoven, music history’s most celebrated Swiss watchmaker, once labelled two three-note fragments of a string quartet movement “Must it be?” and “It must be!” With two tiny phrases, distributed throughout a piece, he told a story. It’s a remarkable achievement, one that musicologists have been drooling over for centuries. ABBA did it too. All hail the three Bs: Beethoven, Benny and Björn.

“Mamma Mia” is ABBA’s best song, a crowning achievement in popular music. It is music heard so deeply that it is not heard at all. You are “Mamma Mia” while “Mamma Mia” lasts.

*I believe the perfect ABBA record collection contains the following: ABBA Gold and The Visitors. The latter is their final LP, and it’s massively more consistent than the rest of their albums. It is also usefully underrepresented on ABBA Gold (only “One of Us” made the cut), so there’s not much in the way of redundancy. There are a handful of worthwhile deep cuts scattered across the other albums—especially Arrival—but nothing that compares with their top-tier hits. (Inconveniently, most of the good stuff from before The Visitors was also left off the hilariously titled collection More ABBA Gold, which is fairly tepid.) Tom Ewing has opined that “every ABBA song has something good about it.” I think that’s quite generous, but I take his point. When you listen to an original ABBA album that isn’t The Visitors, you constantly hear brilliant ideas that you wish were attached to better songs.

The biggest duffer on the disc by a mile. It’s almost a sure bet in the ABBA corpus that a male lead vocal indicates a bad song, and probably also a creepy one, c.f. “

The biggest duffer on the disc by a mile. It’s almost a sure bet in the ABBA corpus that a male lead vocal indicates a bad song, and probably also a creepy one, c.f. “ A music hall number, but the treacly, sentimental kind rather than the fun ironic kind. I hear you ask: how can you be complaining about sentimentality… in an ABBA song??? It’s a valid point.

A music hall number, but the treacly, sentimental kind rather than the fun ironic kind. I hear you ask: how can you be complaining about sentimentality… in an ABBA song??? It’s a valid point.  Charitably, you could read it as a song in the tradition of “Whistle While You Work” or “I Get Along Without You Very Well,” in which the singer is trying as hard as they can to ignore something unpleasant. But “I Have a Dream” doesn’t offer any specifics about what the unpleasant thing is. Moreover, the cheery music makes it seem like the singer’s strategy is actually working. Where’s the tension in that?

Charitably, you could read it as a song in the tradition of “Whistle While You Work” or “I Get Along Without You Very Well,” in which the singer is trying as hard as they can to ignore something unpleasant. But “I Have a Dream” doesn’t offer any specifics about what the unpleasant thing is. Moreover, the cheery music makes it seem like the singer’s strategy is actually working. Where’s the tension in that?  Presumably it made a ton of money for UNICEF. But it’s basically “Blackbird” with a less memorable melody and the panpipes from “El Condor Pasa” grafted on. It is the song on

Presumably it made a ton of money for UNICEF. But it’s basically “Blackbird” with a less memorable melody and the panpipes from “El Condor Pasa” grafted on. It is the song on  It’s weird to me that the compilers of this album shunted so much of the weaker material onto side four. If not for the promise of “Waterloo” to finish, you might be inclined to switch off at the three-quarter mark. I often do.

It’s weird to me that the compilers of this album shunted so much of the weaker material onto side four. If not for the promise of “Waterloo” to finish, you might be inclined to switch off at the three-quarter mark. I often do.  ABBA excelled at writing songs for those of us who do not experience emotional numbness, but rather a surfeit of negative emotion. This song is right in their comfort zone, which is horrible anguish painted in broad strokes of luminous colour. So basically—

ABBA excelled at writing songs for those of us who do not experience emotional numbness, but rather a surfeit of negative emotion. This song is right in their comfort zone, which is horrible anguish painted in broad strokes of luminous colour. So basically— ABBA’s storytelling side isn’t well represented on

ABBA’s storytelling side isn’t well represented on  ABBA songs generally sound either dated or timeless. There isn’t really a lot of middle ground—you’re either rolling your eyes at the audio equivalent of dancing lamé, or you’re marvelling at how these songs could still be hits today. They are either painfully “70s/80s,” or they are ethereally detached from time.

ABBA songs generally sound either dated or timeless. There isn’t really a lot of middle ground—you’re either rolling your eyes at the audio equivalent of dancing lamé, or you’re marvelling at how these songs could still be hits today. They are either painfully “70s/80s,” or they are ethereally detached from time.  It’s all about those synth arpeggios. They’re more than a cool effect—they hold the song together. This is one of ABBA’s secret weapons: a seamless transition from one part of a song to another.

It’s all about those synth arpeggios. They’re more than a cool effect—they hold the song together. This is one of ABBA’s secret weapons: a seamless transition from one part of a song to another.  Quick! What’s your favourite ABBA riff? This is a question you have probably never been asked. (If so, was it me who asked you? Doesn’t count.)

Quick! What’s your favourite ABBA riff? This is a question you have probably never been asked. (If so, was it me who asked you? Doesn’t count.)  Speaking of Tin Pan Alley, here’s a straight up showtune. To my ears, “Money, Money, Money” has one of ABBA’s two or three best arrangements—certainly the most elaborate one on this collection. The song itself is a rueful drama with a fabulous, vampy vocal from a careworn Frida Lyngstad. But it’s the piano and mallet percussion that brings it to life. The restlessly repeating honky-tonk pattern at the start of the verse underscores the anxiety in the lyric. The plunk-plunk-plunk piano line before the chorus, which switches the emphasis pattern halfway through, makes it sound like ABBA called up Irving Berlin for a co-write.

Speaking of Tin Pan Alley, here’s a straight up showtune. To my ears, “Money, Money, Money” has one of ABBA’s two or three best arrangements—certainly the most elaborate one on this collection. The song itself is a rueful drama with a fabulous, vampy vocal from a careworn Frida Lyngstad. But it’s the piano and mallet percussion that brings it to life. The restlessly repeating honky-tonk pattern at the start of the verse underscores the anxiety in the lyric. The plunk-plunk-plunk piano line before the chorus, which switches the emphasis pattern halfway through, makes it sound like ABBA called up Irving Berlin for a co-write.  Misery. Destitution. Dolor. Regret. Classic ABBA.

Misery. Destitution. Dolor. Regret. Classic ABBA.  It might be the ABBA song where the pieces fit together the best. And there are a lot of pieces. Six chirpy chords off the top evaporate into a dramatic, torchy minor key verse. The chorus starts with a title drop and chunky guitar chords. Seconds later, we’ve gotten to “breaking up is never easy,” and the song’s finally made it to its major key home. (Like Schubert, ABBA gets sadder when they’re in a major key.) The chorus gives way to the riff half a measure before you expect it to. A pair of electric guitars wails at each other while one of them dies of consumption, and we’re back into the verse.

It might be the ABBA song where the pieces fit together the best. And there are a lot of pieces. Six chirpy chords off the top evaporate into a dramatic, torchy minor key verse. The chorus starts with a title drop and chunky guitar chords. Seconds later, we’ve gotten to “breaking up is never easy,” and the song’s finally made it to its major key home. (Like Schubert, ABBA gets sadder when they’re in a major key.) The chorus gives way to the riff half a measure before you expect it to. A pair of electric guitars wails at each other while one of them dies of consumption, and we’re back into the verse. Anxiety disco in a gothic cathedral. Imagine those opening synth chords played on a gigantic church organ. “Lay All Your Love On Me” is a perversely liturgical-sounding song. It is borderline blasphemous; daemonic.

Anxiety disco in a gothic cathedral. Imagine those opening synth chords played on a gigantic church organ. “Lay All Your Love On Me” is a perversely liturgical-sounding song. It is borderline blasphemous; daemonic. The first few times I listened to “Super Trouper,” I thought it was about the transformative power of performance—how the thankless grind of touring evaporates into ecstasy when the narrator goes onstage. I was hearing what I wanted to hear. Those of us who are not pop stars would like to think it’s a rewarding life; that the artists we choose as vessels for our own dreams are in fact “living the dream.”

The first few times I listened to “Super Trouper,” I thought it was about the transformative power of performance—how the thankless grind of touring evaporates into ecstasy when the narrator goes onstage. I was hearing what I wanted to hear. Those of us who are not pop stars would like to think it’s a rewarding life; that the artists we choose as vessels for our own dreams are in fact “living the dream.”  I am

I am  ABBA’s disco apotheosis. Leave it to them to write a song designed for dancing, which also explicitly points out the dark side of why people go out at night. It’s the same reason

ABBA’s disco apotheosis. Leave it to them to write a song designed for dancing, which also explicitly points out the dark side of why people go out at night. It’s the same reason  I could go on forever about how every great ABBA song is a dark psychodrama dressed up in pastel colours. But really, everybody already knows that. The real reason ABBA songs are so good is that their hooks are a hit of pure dopamine, even when melancholy does register.

I could go on forever about how every great ABBA song is a dark psychodrama dressed up in pastel colours. But really, everybody already knows that. The real reason ABBA songs are so good is that their hooks are a hit of pure dopamine, even when melancholy does register.  There are more cathartic ABBA songs than “Mamma Mia.” There are more expressive and sincere ABBA songs too, that reflect listeners back at themselves more uncannily. But, look. If that’s all that ABBA songs were, they wouldn’t stand up to the kind of compulsive repeat listening that they do. The real reason that ABBA is a great band has nothing to do with their ability to articulate specific human emotions. Hundreds of bands can do that. What makes ABBA special is that they write music that feels like it’s always existed. I can’t explain it any better than that. The first time you hear a great ABBA song, it’s like becoming aware of a natural condition of the human mind that you hadn’t previously noticed, but which was always there. “Earworm” doesn’t begin to describe it. An ABBA song can become a part of you. That’s never been truer than in the case of “Mamma Mia,” because “Mamma Mia” is almost elementally simple—it is built with the smallest possible building blocks.

There are more cathartic ABBA songs than “Mamma Mia.” There are more expressive and sincere ABBA songs too, that reflect listeners back at themselves more uncannily. But, look. If that’s all that ABBA songs were, they wouldn’t stand up to the kind of compulsive repeat listening that they do. The real reason that ABBA is a great band has nothing to do with their ability to articulate specific human emotions. Hundreds of bands can do that. What makes ABBA special is that they write music that feels like it’s always existed. I can’t explain it any better than that. The first time you hear a great ABBA song, it’s like becoming aware of a natural condition of the human mind that you hadn’t previously noticed, but which was always there. “Earworm” doesn’t begin to describe it. An ABBA song can become a part of you. That’s never been truer than in the case of “Mamma Mia,” because “Mamma Mia” is almost elementally simple—it is built with the smallest possible building blocks.