I try to format this list a little differently every year. Nevertheless, they all have one thing in common: they are always incredibly long. Let’s try something really new. This year, I present a tight seven, appraised briefly with a minimum of honourable mentioning. Here goes.

Best Television: Culinary Class Wars

For the second year running, not a single scripted television program I watched could compete with the rapturous gloss, detail and complexity of a Korean competition show. Culinary Class Wars is, beyond a shadow of doubt, the best cooking show I’ve ever seen. Before its premiere, my partner and I had been watching a lot of Masterchef. We can never go back. We have been spoiled by the brilliance of this. Culinary Class Wars features both traditional comfort food and haute cuisine, but at no point does anybody refer to the need to “elevate” a dish. We witness the tension of skilled chefs working under unrealistic deadlines, but the editing never suggests that something may go horribly wrong that ultimately doesn’t. And the judges, while almost comically exacting, are never rude. In particular, they are never performatively rude for the camera’s benefit.

To say too much more would be to ruin the sense of discovery you’ll get from going in cold: not just the discovery of who wins and who cooks what, but the discovery of what kinds of characters even show up on a show like this. I will say two final things to pique interest. Firstly, the specific events that the competitors are obliged to take part in are enormously more taxing than anything I’ve ever seen on an American cooking show. In some jurisdictions, they would surely run afoul of labour laws. And secondly, in the semifinals, one particular chef does perhaps five or six of the most astonishing things I’ve ever seen anybody do with food, within the span of only three real-world hours.

I’ve largely lost my appetite for television in this era of Mid TV. This year, even some of the shows I was genuinely excited for left me feeling like they’d wasted my time (not to mention Cate Blanchett’s). But a couple of scripted shows stood out. The Curse is a miracle of behavioural comedy, featuring maybe Emma Stone’s best performance and a finale worthy of Twin Peaks. And Ripley is a genuinely cinematic adaptation of a classic story, in a medium that is quickly transforming into radio with pictures.

Best Movie: Perfect Days

I missed this at TIFF 2023, so it’s a 2024 film to me.

The logline of Wim Wenders’ gorgeous film might make it sound like a stunt or a provocation in the vein of the Nicholas Cage movie Pig. It might go something like, “a film about cleaning toilets, except the film is life-affirming.” This summary, while accurate, suggests that the disparity between the film’s subject matter and its incredible beauty might be meant to create some sort of cognitive dissonance: that Perfect Days is somehow perverse. It is absolutely not perverse. It is an utterly sincere and almost innocent film about a man who has learned how to be happy most of the time, dirty toilets or no.

Kōji Yakusho is nearly silent in the lead role, so we leave the cinema largely ignorant of his insights. Perfect Days regrettably does not function as a self-help manual. But it does something better, a Wim Wenders speciality (he does it in Wings of Desire as well): it persuades you that Humanity Is Good.

I saw fewer new movies this year than any other year since lockdown, and only a handful really floored me. Notably, Dune: Part Two is the first version of that story that I have found completely satisfying. Its oddness and spectacle have essentially overwritten my memories of the novel that is its source, David Lynch’s creative nadir, Alejandro Jodorowsky’s spectral recollections, and even this new film’s own predecessor. Anora is a surprisingly frothy film for most of its duration, while also building a wonderful portrait of a marginalised character and illustrating how capitalism poisons everything. The other film I truly loved this year, Rebel Ridge, made me a confirmed devotee of Jeremy Saulnier. He’s one of vanishingly few filmmakers dedicated to making realistic thrillers, all the more realistic since his villains–neo-Nazis and abusive, corrupt cops–are people you could see on the news.

Best Album: Sparagmos, Spectral Voice

By most reckonings, Spectral Voice is a side project of the massively successful prog metal project Blood Incantation. So, Sparagmos isn’t even this approximate collection of musicians’ highest profile release of the year. Blood Incantation’s Absolute Elsewhere is almost certainly the most acclaimed metal album of 2024. But I spent much more time with this release by their shadowy mirror twin, which is eviler by far. The fact that “sparagmos” is an ancient Dionysian ritual makes the metaphor almost too obvious. Where Absolute Elsewhere is striving, Apollonian music of transcendence through knowledge, Sparagmos is intuitive, dark and impulse driven. It is murky and doomed.

It is the only top choice on this essentially optimistic and affirmational list that strikes that mood. Maybe I needed it this year, to help maintain perspective.

And now: new music from an old favourite, a new favourite, and a favourite that’s newish to me. Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s comeback hasn’t been entirely consistent, but No Title as of 13 February 2024, 28,340 Dead is a career highlight–as stark and strident as its non-title. The existence of Geordie Greep’s solo career is distressing in itself, since it implies the end of his old band Black Midi, before I even got to see them. But The New Sound is a small miracle, blending some Thumpasaurusy meme funk tendencies with a genuine gift for extended form. And Four Tet’s Three was the ideal workout companion for several months, touching on nearly every mood in his kaleidoscopic catalogue.

Best Game: 1000xRESIST

It’s absurdly easy for me to choose my favourite video game of all time, much easier than the same choice in any other medium. It’s Kentucky Route Zero. I love that specific game more than I love video games. I’ve played more than a handful of games that are clearly going after what KRZ did so well. Some of them are great. But none of them have KRZ’s lightning in a bottle originality. 1000xRESIST does.

This is a game that, like KRZ, deals with the fallout of recent history: in this case the 2019 Hong Kong protests and the pandemic. Like KRZ, it is suffused with real-world melancholy over the way that social forces have shaped its characters’ lives. Like KRZ, its presentation changes in novel ways from moment to moment. But the atmosphere and preoccupations of 1000xRESIST are entirely its own. Its story and aesthetic are built from scraps of anime, Kojima games and Final Fantasy. Ultimately, I think the main thing the two games have in common is that they were both made by teams with more experience in other media than in games, experience that helps bring originality to their approach, and enables them to sidestep every cliché.

Bizarrely, I interviewed this game’s director, Remy Siu, many years ago in an almost entirely different context. I’d just seen the premiere of a musical performance piece of his called Foxconn Frequency (no. 2) — for one visibly Chinese pianist. The gist is that the performer has to play incredibly difficult exercises on an electric keyboard, amidst a clamorous multimedia stage environment, and can’t move on until they get it right. Different as it is, I’m pretty sure everything Siu told me about that piece is in 1000xRESIST somewhere as well. I should have seen it coming.

This was the most contentious category. I considered two others for the top spot: Lorelei and the Laser Eyes and Balatro. But I’ll be giving plenty of attention to Lorelei soon enough, and I’ve played Balatro so compulsively this year that it’s starting to feel like I ate too much Halloween candy. Both games are ingenious, but neither got under my skin like 1000xRESIST. The other runners-up are Judero, a handmade stop motion adventure game whose somewhat tedious combat doesn’t at all detract from its atmosphere or the wonderful oddness of its NPCs, and 20 Small Mazes, which actually is just 20 small mazes. But they’re very good mazes.

Best Book: The Work of Art, Adam Moss

While I read more than usual this year, I’m afraid this one wins its category by default. Turns out, when I don’t have half my mind turned towards a year-end blog post that a tiny handful of people will even see, I don’t read new books. But the one new book I did read this year is a truly stunning object. Moss was the longtime editor-in-chief of New York magazine, among others. His first book as an author rather than an editor is, and I mean this as a compliment, a huge magazine. It contains 43 features on notable artists and their processes, lavishly illustrated with sketches, scraps, outlines and notes-to-self. The artists featured are always a delight to read, and Moss is a wonderful tour guide through their minds. But it’s this documentary evidence that steals the show: process in still life.

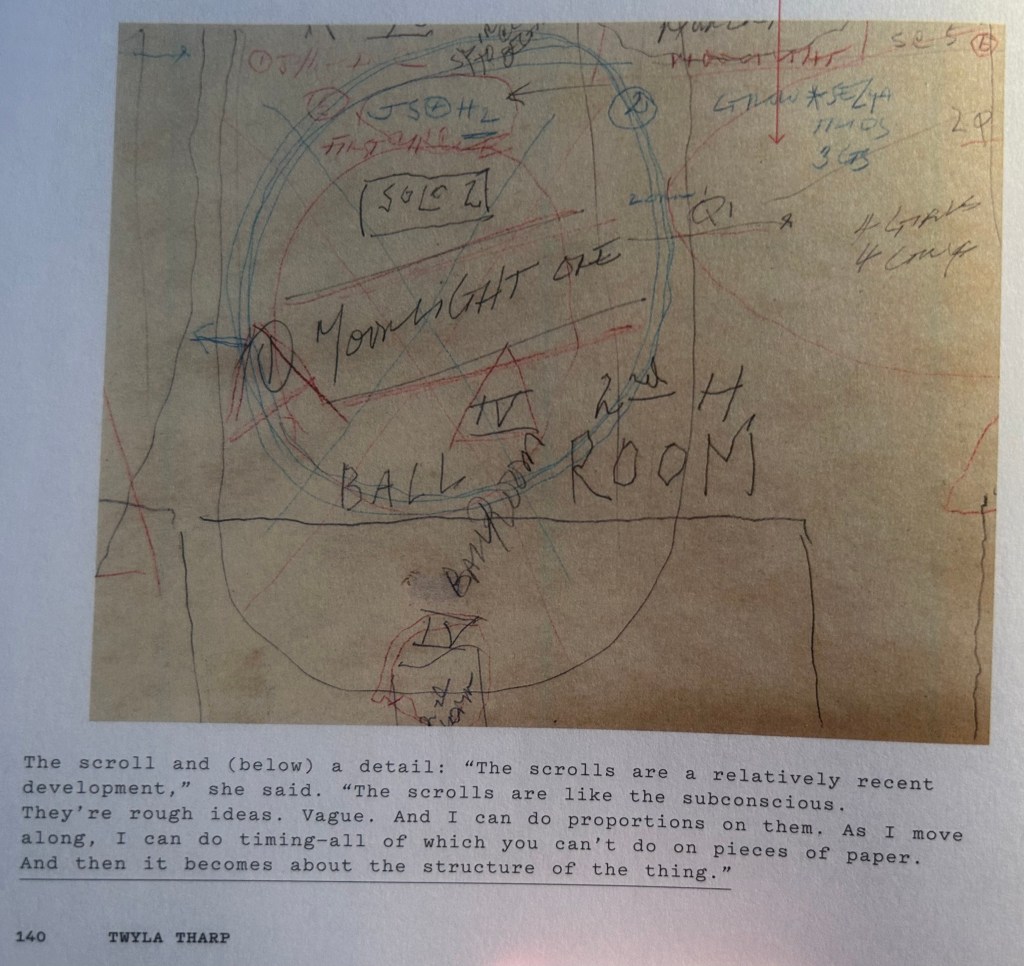

Moss shows us Twyla Tharp’s studio-spanning scroll, on which she details her choreography in a language that’s only legible to her. He shows us the multiple versions considered of two specific jokes in Veep. He shows us studies and sketches by artists that may in their rough emptiness be more poignant than the finished product. It’s an avalanche of fragments, a fragmalanche, and it reinvigorated my urge to make things, over and over and over.

I had considered the notion of “curation” as a focus for this list. Had I gone through with it, this might have served as a sort of sequel to last year’s list, wherein curation becomes my latest alternative to frustrating, modern narrative experiences: instead of telling a linear story, you can simply place things next to each other. I decided against it in the end, possibly because I lived through the halcyon days of clickbait, and I’m not sure the word “curation” will ever be purged of that era’s evil associations. Also, the theme probably wouldn’t have applied to much aside from this book and a handful of games: Lorelei and the Laser Eyes, The Story of Llamasoft, and the latter’s fictional counterpart UFO 50 (which I didn’t even play). This paragraph is as much as I can muster on the topic.

Best Podcast: Benjamen Walker’s Theory of Everything

Benjamen Walker is a podcasting OG with essentially no competitors. We’re a decade into the era of narrative podcast oversaturation, and there still isn’t anybody else who really does what Walker does: a blend of fiction and non-fiction, essays and interviews, often built around ideas that some would consider simply too abstract for radio. This year, the main event on the Theory of Everything feed was Walker’s series Not All Propaganda Is Art, a nine-part group biography of three 20th-century writers with ties to the CIA: Richard Wright, Kenneth Tynan and Dwight Macdonald. It is a titanic work, not only in its architecture but in the research that obviously undergirds it–Walker located not just one but two films that were previously considered lost in the course of making this series. It is one of the vanishingly rare history podcasts that tells you things you couldn’t have previously learned by Googling them.

It is also a proof-of-concept for the whole idea of a podcast group biography. Should anybody else take up the torch, I hope they’ll follow Walker’s lead in thinking as a radio producer first, a writer second. By necessity, he tells most of his story through a written script. But the show is built around documentary evidence: recordings of lectures, film clips, television interviews, etc. that are present here not just for colour, but as the central pillar of Walker’s argument. In a just world, this would be the moment when Walker finally acquired imitators. But I doubt anyone has the energy.

Most of my listening this year was to the same handful of chat podcasts that have made the list over the last several years, but I’ve added some new ones to the stable. Unexpectedly, the best of them comes from one of the godfathers of narrative podcasting: Roman Mars. The 99% Invisible breakdown of The Power Broker by Robert Caro is the platonic ideal of a chat podcast, featuring an smart host who’s also surprisingly funny (Mars), and a funny co-host who’s also surprisingly smart (Elliot Kalan). I did not read along with them, but if I ever pick up that brick of a tome, I’ll listen again. Finally, In the Dark maintains its crown as the best and most virtuous investigative podcast around. Its third season revolves around the infamous mass killing of civilians in Haditha by American marines during the Iraq war. Like its predecessors, the smaller story serves to illustrate a broader systemic reality–one that in this case will only become more troubling throughout the second Trump administration.

Bonus: Jon Bois

If I were following the format, this would be an endorsement of Secret Base, the freewheeling sports-focussed YouTube channel associated with SB Nation. But really, I’ve only been following their creative director, Jon Bois, who created two extraordinary works this year that have nothing to do with sports. One is a data driven (all of Bois’ work is data driven but nobody ever phrases it that way because you don’t say that about funny people) history of America’s essentially defunct Reform Party. It’s one of the most entertaining works of non-fiction I’ve ever seen about American politics.

Unfortunately, Bois’s recent video essay about how many people slip on banana peels is even better.

Tally ‘em up and that’s 21 things I loved. You want an even 25? Fine. Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story, Corb Lund’s El Viejo, M. Night Shamalan’s Trap, and The London Review of Books. Are we done here?

The biggest duffer on the disc by a mile. It’s almost a sure bet in the ABBA corpus that a male lead vocal indicates a bad song, and probably also a creepy one, c.f. “

The biggest duffer on the disc by a mile. It’s almost a sure bet in the ABBA corpus that a male lead vocal indicates a bad song, and probably also a creepy one, c.f. “ A music hall number, but the treacly, sentimental kind rather than the fun ironic kind. I hear you ask: how can you be complaining about sentimentality… in an ABBA song??? It’s a valid point.

A music hall number, but the treacly, sentimental kind rather than the fun ironic kind. I hear you ask: how can you be complaining about sentimentality… in an ABBA song??? It’s a valid point.  Charitably, you could read it as a song in the tradition of “Whistle While You Work” or “I Get Along Without You Very Well,” in which the singer is trying as hard as they can to ignore something unpleasant. But “I Have a Dream” doesn’t offer any specifics about what the unpleasant thing is. Moreover, the cheery music makes it seem like the singer’s strategy is actually working. Where’s the tension in that?

Charitably, you could read it as a song in the tradition of “Whistle While You Work” or “I Get Along Without You Very Well,” in which the singer is trying as hard as they can to ignore something unpleasant. But “I Have a Dream” doesn’t offer any specifics about what the unpleasant thing is. Moreover, the cheery music makes it seem like the singer’s strategy is actually working. Where’s the tension in that?  Presumably it made a ton of money for UNICEF. But it’s basically “Blackbird” with a less memorable melody and the panpipes from “El Condor Pasa” grafted on. It is the song on

Presumably it made a ton of money for UNICEF. But it’s basically “Blackbird” with a less memorable melody and the panpipes from “El Condor Pasa” grafted on. It is the song on  It’s weird to me that the compilers of this album shunted so much of the weaker material onto side four. If not for the promise of “Waterloo” to finish, you might be inclined to switch off at the three-quarter mark. I often do.

It’s weird to me that the compilers of this album shunted so much of the weaker material onto side four. If not for the promise of “Waterloo” to finish, you might be inclined to switch off at the three-quarter mark. I often do.  ABBA excelled at writing songs for those of us who do not experience emotional numbness, but rather a surfeit of negative emotion. This song is right in their comfort zone, which is horrible anguish painted in broad strokes of luminous colour. So basically—

ABBA excelled at writing songs for those of us who do not experience emotional numbness, but rather a surfeit of negative emotion. This song is right in their comfort zone, which is horrible anguish painted in broad strokes of luminous colour. So basically— ABBA’s storytelling side isn’t well represented on

ABBA’s storytelling side isn’t well represented on  ABBA songs generally sound either dated or timeless. There isn’t really a lot of middle ground—you’re either rolling your eyes at the audio equivalent of dancing lamé, or you’re marvelling at how these songs could still be hits today. They are either painfully “70s/80s,” or they are ethereally detached from time.

ABBA songs generally sound either dated or timeless. There isn’t really a lot of middle ground—you’re either rolling your eyes at the audio equivalent of dancing lamé, or you’re marvelling at how these songs could still be hits today. They are either painfully “70s/80s,” or they are ethereally detached from time.  It’s all about those synth arpeggios. They’re more than a cool effect—they hold the song together. This is one of ABBA’s secret weapons: a seamless transition from one part of a song to another.

It’s all about those synth arpeggios. They’re more than a cool effect—they hold the song together. This is one of ABBA’s secret weapons: a seamless transition from one part of a song to another.  Quick! What’s your favourite ABBA riff? This is a question you have probably never been asked. (If so, was it me who asked you? Doesn’t count.)

Quick! What’s your favourite ABBA riff? This is a question you have probably never been asked. (If so, was it me who asked you? Doesn’t count.)  Speaking of Tin Pan Alley, here’s a straight up showtune. To my ears, “Money, Money, Money” has one of ABBA’s two or three best arrangements—certainly the most elaborate one on this collection. The song itself is a rueful drama with a fabulous, vampy vocal from a careworn Frida Lyngstad. But it’s the piano and mallet percussion that brings it to life. The restlessly repeating honky-tonk pattern at the start of the verse underscores the anxiety in the lyric. The plunk-plunk-plunk piano line before the chorus, which switches the emphasis pattern halfway through, makes it sound like ABBA called up Irving Berlin for a co-write.

Speaking of Tin Pan Alley, here’s a straight up showtune. To my ears, “Money, Money, Money” has one of ABBA’s two or three best arrangements—certainly the most elaborate one on this collection. The song itself is a rueful drama with a fabulous, vampy vocal from a careworn Frida Lyngstad. But it’s the piano and mallet percussion that brings it to life. The restlessly repeating honky-tonk pattern at the start of the verse underscores the anxiety in the lyric. The plunk-plunk-plunk piano line before the chorus, which switches the emphasis pattern halfway through, makes it sound like ABBA called up Irving Berlin for a co-write.  Misery. Destitution. Dolor. Regret. Classic ABBA.

Misery. Destitution. Dolor. Regret. Classic ABBA.  It might be the ABBA song where the pieces fit together the best. And there are a lot of pieces. Six chirpy chords off the top evaporate into a dramatic, torchy minor key verse. The chorus starts with a title drop and chunky guitar chords. Seconds later, we’ve gotten to “breaking up is never easy,” and the song’s finally made it to its major key home. (Like Schubert, ABBA gets sadder when they’re in a major key.) The chorus gives way to the riff half a measure before you expect it to. A pair of electric guitars wails at each other while one of them dies of consumption, and we’re back into the verse.

It might be the ABBA song where the pieces fit together the best. And there are a lot of pieces. Six chirpy chords off the top evaporate into a dramatic, torchy minor key verse. The chorus starts with a title drop and chunky guitar chords. Seconds later, we’ve gotten to “breaking up is never easy,” and the song’s finally made it to its major key home. (Like Schubert, ABBA gets sadder when they’re in a major key.) The chorus gives way to the riff half a measure before you expect it to. A pair of electric guitars wails at each other while one of them dies of consumption, and we’re back into the verse. Anxiety disco in a gothic cathedral. Imagine those opening synth chords played on a gigantic church organ. “Lay All Your Love On Me” is a perversely liturgical-sounding song. It is borderline blasphemous; daemonic.

Anxiety disco in a gothic cathedral. Imagine those opening synth chords played on a gigantic church organ. “Lay All Your Love On Me” is a perversely liturgical-sounding song. It is borderline blasphemous; daemonic. The first few times I listened to “Super Trouper,” I thought it was about the transformative power of performance—how the thankless grind of touring evaporates into ecstasy when the narrator goes onstage. I was hearing what I wanted to hear. Those of us who are not pop stars would like to think it’s a rewarding life; that the artists we choose as vessels for our own dreams are in fact “living the dream.”

The first few times I listened to “Super Trouper,” I thought it was about the transformative power of performance—how the thankless grind of touring evaporates into ecstasy when the narrator goes onstage. I was hearing what I wanted to hear. Those of us who are not pop stars would like to think it’s a rewarding life; that the artists we choose as vessels for our own dreams are in fact “living the dream.”  I am

I am  ABBA’s disco apotheosis. Leave it to them to write a song designed for dancing, which also explicitly points out the dark side of why people go out at night. It’s the same reason

ABBA’s disco apotheosis. Leave it to them to write a song designed for dancing, which also explicitly points out the dark side of why people go out at night. It’s the same reason  I could go on forever about how every great ABBA song is a dark psychodrama dressed up in pastel colours. But really, everybody already knows that. The real reason ABBA songs are so good is that their hooks are a hit of pure dopamine, even when melancholy does register.

I could go on forever about how every great ABBA song is a dark psychodrama dressed up in pastel colours. But really, everybody already knows that. The real reason ABBA songs are so good is that their hooks are a hit of pure dopamine, even when melancholy does register.  There are more cathartic ABBA songs than “Mamma Mia.” There are more expressive and sincere ABBA songs too, that reflect listeners back at themselves more uncannily. But, look. If that’s all that ABBA songs were, they wouldn’t stand up to the kind of compulsive repeat listening that they do. The real reason that ABBA is a great band has nothing to do with their ability to articulate specific human emotions. Hundreds of bands can do that. What makes ABBA special is that they write music that feels like it’s always existed. I can’t explain it any better than that. The first time you hear a great ABBA song, it’s like becoming aware of a natural condition of the human mind that you hadn’t previously noticed, but which was always there. “Earworm” doesn’t begin to describe it. An ABBA song can become a part of you. That’s never been truer than in the case of “Mamma Mia,” because “Mamma Mia” is almost elementally simple—it is built with the smallest possible building blocks.

There are more cathartic ABBA songs than “Mamma Mia.” There are more expressive and sincere ABBA songs too, that reflect listeners back at themselves more uncannily. But, look. If that’s all that ABBA songs were, they wouldn’t stand up to the kind of compulsive repeat listening that they do. The real reason that ABBA is a great band has nothing to do with their ability to articulate specific human emotions. Hundreds of bands can do that. What makes ABBA special is that they write music that feels like it’s always existed. I can’t explain it any better than that. The first time you hear a great ABBA song, it’s like becoming aware of a natural condition of the human mind that you hadn’t previously noticed, but which was always there. “Earworm” doesn’t begin to describe it. An ABBA song can become a part of you. That’s never been truer than in the case of “Mamma Mia,” because “Mamma Mia” is almost elementally simple—it is built with the smallest possible building blocks.