If you’re one of the three people wondering why I still haven’t finished Moby-Dick, here is part of the answer: I’ve been extremely busy reading Stephen King. It started in 2017, when King became suddenly more zeitgeisty than he’d been since probably the ‘80s. This was the year of the first recent It movie, and the second season of Stranger Things. It was also the year of the derided film adaptation of King’s most ambitious work: the Dark Tower series. The movie’s release might have been the first I heard of the Dark Tower. And its reception among reviewers who’d read the novel was my first indication that maybe I should finally read something by King.

I don’t remember any one review in particular. But I remember getting the sense that this by-the-numbers Hollywood blockbuster (allegedly; I haven’t seen it) was working to adapt something beyond cinema’s capacity: something closer to outsider art than to the eminently adaptable novels that made King into the multimedia sensation he is. A tantalizing prospect – a resolutely personal seven-volume drafts folder, written by the most successful popular novelist alive with no eye towards mass appeal, or even coherence. This is my shit. This is what I live for. This is why I’ve now read the whole Dark Tower series and several King obscurities, and I still haven’t read The Shining.

If this is somehow your first point of contact with the Dark Tower series altogether, the basic premise is this: Roland Deschain is the last of a long line of wild west gunslingers who are literally descended from King Arthur, and who once served as defenders of the natural order in a high-fantasy setting that has since deteriorated into wastes. Roland feels that this damage might be reversible if only he can make it to the Dark Tower, the nature of which is initially unclear. In his travels, he makes many unsettling discoveries, chief among them that his world is porous, and contains many passages into other realities altogether, which allows his story to intersect wantonly with stories from other, initially unrelated books by Stephen King.

There are many (too many) knowledgeable guides to the Dark Tower on the internet, detailing what you should read when, and piecing together the connections between the officially demarcated Dark Tower novels and the many many other books in King’s canon that intersect with them. This is my idiosyncratic and personal version of that. It is less complete than many (I haven’t read anything co-written by Peter Straub, and I’m not touching The Regulators, thanks) but hopefully by not pretending to total authority I can help somebody have their own specific and personal reading experience.

Before I read the Dark Tower series, it always seemed like gatekeeping to me when somebody said that you need to read a half-dozen other books to have a Truly Complete Experience. I admired the writers who boldly claimed that all you need to read if you want to read the Dark Tower series is… the Dark Tower series. But I’m afraid I don’t agree. As Cameron Kunzelman observed on the fantastic Just King Things podcast, the series’ controversial final instalments are simply more interesting if you have a sense of King’s development over the long gestation of the series. I’d put it this way: you need an almost personal relationship with Stephen King if you’re ever going to enjoy Song of Susannah. And, contrary to popular opinion, that book can in fact be enjoyed.

Here’s how this will work. The second part of this post will be a ranking of the eight official Dark Tower books (including The Wind Through the Keyhole). Tedious, I know. But frankly, all of the Dark Tower novel rankings I read before I started gave me a very different sense of what the good shit is than I actually experienced myself. If I can counterbalance a bit of conventional wisdom here, great. I’d love for you to start reading these books with absolutely no preconceptions about which ones you’ll like best.

But first, I’m going to go through every Tower-related book I read, in the order that I read them. Why should you care what order I read them in? What authority do I have? Only this: I loved reading the Dark Tower series, and I feel like the order in which I read the various related materials has something to do with how much I loved it. If you were to replicate it exactly, who knows whether it would work as well for you. But here it is all the same. In an effort to offer a more concrete service, I have rated every book out of ten for both its excellence and its Tower-relevance. Let these metrics guide your choices.

A final note before we begin: the only King novel I’ve read that has essentially nothing to do with the Dark Tower in my opinion is Carrie. But if you’re interested in cultivating that personal relationship with the writer, I really think Carrie is worth reading around the same time you read ‘Salem’s Lot. They’re the first two books of King’s career, and they are the reason why he became the writer he did. All the same, this is a fringe argument, so I’m not putting Carrie on the reading list proper.

Oh also, I’m going to try really hard not to spoil anything. If you’re deeply spoiler sensitive you probably shouldn’t read this, but let’s all be reasonable. I’m writing this assuming that you’ve read none of these books. In my opinion nothing discussed here should affect your experience of the story.

Here goes.

Part One: Related Reading

On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft

Placement: After The Gunslinger (book 1)

Excellence: 9

Tower-relevance: 7

We might as well begin with the weirdest inclusion on the list. I really think that if you want to get the most out of the Dark Tower (the last two books in particular), you need to read On Writing. It is a work of nonfiction, so how related could it possibly be? Honestly: pretty related. Reality is famously porous in the Dark Tower series, so it stands to reason that some events from our world might become relevant at some point.

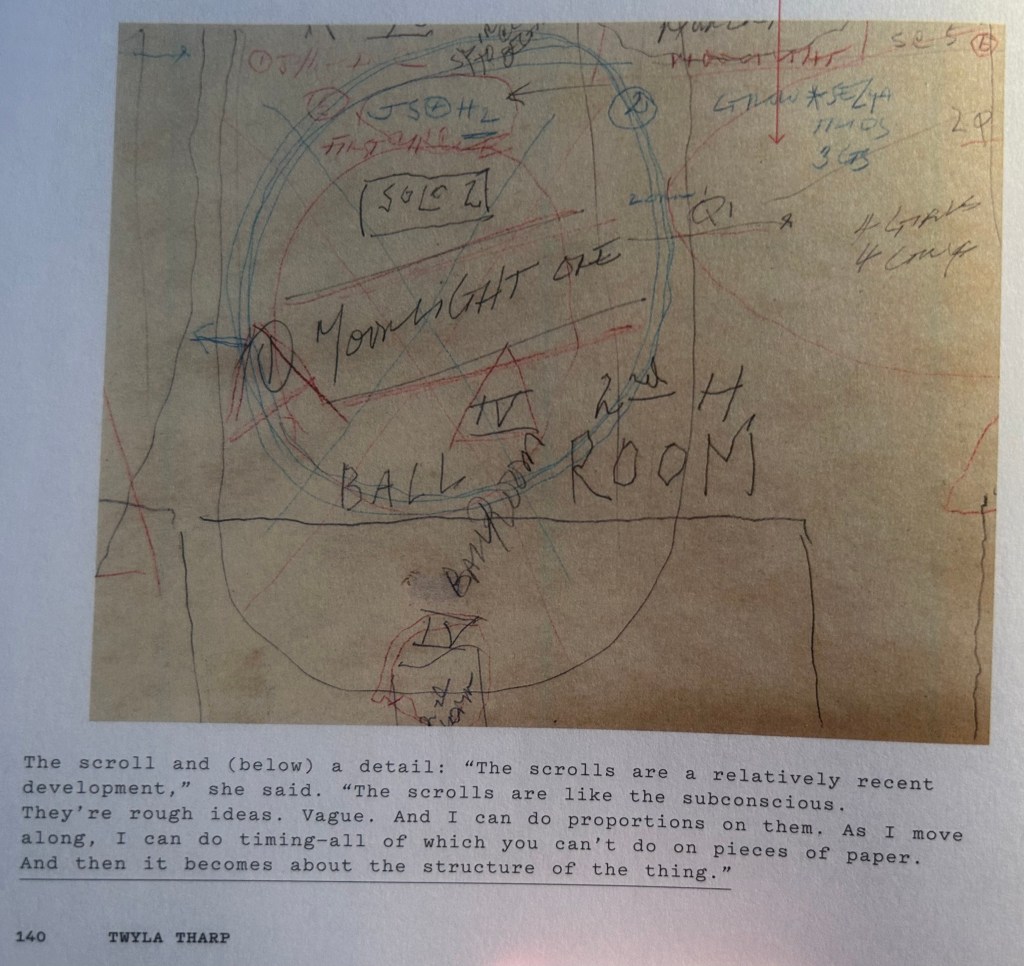

This modest autobiography/creativity self-help manual is one of my favourite things King has ever written. Rather than attempt to chart a reliable course towards literary success, King uses his own life as an example of one way it’s been done. His story is defined more by tenacity and good fortune than by the vague notion of “talent,” and perhaps the single most useful thing anybody has written about writing is King’s assertion that you learn it by doing a lot of it.

I encourage you to read this early in your Dark Tower experience. I read it around the same time I wolfed down The Gunslinger and The Drawing of the Three (my first two King novels, perhaps bizarrely). Even before the content of On Writing became surprisingly germane to the Dark Tower’s story, I felt more attached to everything I subsequently read from knowing a bit about King’s life and process. King will be your travelling companion for a good, long time. Let him introduce himself.

It

Placement: After The Waste Lands (book 3)

Excellence: 10

Tower-relevance: 4

It is genuinely optional reading from a Dark Tower-focussed perspective. But: it’s fucking good. It is famously messy, arguably overlong, and contains some truly problematic shit. I don’t care. It’s one of the best genre novels I’ve ever read.

In a sense, It embodies the same tendency as the whole Dark Tower series: undisciplined maximalism that’s brimming with ideas and light on actual story. The difference is that It has been successfully adapted not just once but twice, both times focussing on the iconic central image of Pennywise the Dancing Clown. From the adaptations, and the way they’ve woven their way into the public imagination (full disclosure: of these, I’ve only seen It: Chapter One from 2017), you’d think the whole book was about some kids and a scary clown. It isn’t.

It’s connection to the Dark Tower is limited to a brief moment near the end. But: it’s got a spiritual sequel that is significantly more Tower-related, which we’ll be discussing later. More to the point: if you find that the Tower has cultivated your taste for King at his most sprawling, It is essential. Read it at any time; just make sure you get to it before Insomnia.

The Stand

After The Waste Lands (book 3)

Excellence: 6

Tower-relevance: 8

If there are any Constant Readers in the audience, maybe this is where I lose them. Go then, there are other opinions than these.

The Stand is the most acclaimed book Stephen King has ever written. I cannot imagine why. The Stand is a huge slog, especially in its definitive Complete and Uncut Edition. It has a lot of good stuff distributed throughout its 1,152 pages, but it also has even thinner characters than King normally writes and makes us spend more time with them than ever. My vague dislike might have something to do with my particular experience of reading it: I started it shortly before COVID, had no desire to resume reading a pandemic apocalypse story during an actual pandemic, and eventually got through the second half several years after I started. I am seemingly in the minority of people who actually prefer the book’s second half – though I agree with the larger contingent of readers who find the ending idiotic.

Listen. You should probably read The Stand. Chances are, you’ll like it better than I do. It is also the book that introduces Randall Flagg, King’s most iconic villain. Flagg is a significant presence in the Dark Tower novels, though less significant than some would have it. (The Man in Black who makes his first appearance in sentence one of The Gunslinger was originally intended to be a separate character, only to be retconned into Flagg later on.) And the setting and story of The Stand are relevant to the frame narrative of the fourth Dark Tower novel, Wizard and Glass. The somewhat self-contained nature of both Wizard and Glass and Flagg himself in the series makes me inclined to believe The Stand is skippable. But if you’re already planning to read thousands and thousands of pages of Dark Tower-related King novels, not reading The Stand is probably perverse. Just before Wizard and Glass is the only appropriate place for it.

The Eyes of the Dragon

Placement: After The Waste Lands (book 3)

Excellence: 7

Tower-relevance: 7

Some general advice: I think it’s a good idea to focus your additional Tower reading in two big chunks. I personally read On Writing and It concurrently with the first few novels in the series, and you can feel free to do the same. But overall, I think the best places to lump in all of these other books are just before Wizard and Glass, and just after. These are the points where King took a good long break from the series. This is also where the Dark Tower begins to tick upward in its intertextual tendencies. In a moment, I’m going to argue there are four books you should try to read during the second of these breaks, just before you pick up Wolves of the Calla. In the first break, before Wizard and Glass, there are only two: The Stand and The Eyes of the Dragon.

The Eyes of the Dragon is mainly relevant to the Dark Tower for the same reason as The Stand: Flagg. The version of Flagg that surfaces here is markedly different from the one who shows up in that earlier novel, or in the Dark Tower: almost an emanation of The Stand’s Flagg, rather than a concretely related character. There are other connections between this novel and the Tower, but overall the reason I recommend it is because it’s a rollicking good read, and totally different from anything else on the list. The first half in particular is finely-wrought palace intrigue that’s completely unexpected from King.

It is also fairly short. If my distaste for The Stand has dissuaded you, just read this instead.

Insomnia

Placement: After Wizard and Glass (book 4)

Excellence: 7

Tower-relevance: 8

We’ve hit a crucial point, now. All the rest of the books on this related reading list are the ones I packed in between Wizard and Glass and Wolves of the Calla. Famously, King was hit by a van and nearly killed during this period of his career. His first order of business upon recovery was to finally finish the series he’d been putting off for years. The last three Dark Tower novels are a trilogy in themselves. Even more than their predecessors, they bring together threads and characters from throughout King’s body of work. It’s worth doing a little extra homework before taking them on. And you should probably start with Insomnia.

Insomnia is not a well-regarded book. Fair enough: it’s slow and inscrutable, and finds King attempting to grapple with abortion. (This does not go as badly as you might expect, but the sheer tension of reading a book from the ‘90s by a famous man on this topic might decrease your enjoyment.) But personally, I find it pleasantly bonkers. By this time you may be growing weary of King’s stock characters: the self-involved quippy dude, the tenacious boy, the idiot savant, The Woman, etc. Here, King circumvents that tendency by writing a story almost entirely about elderly people. It also contains simply the strangest depiction of supernatural abilities in King’s whole corpus. It wasn’t always fun to read, but I kind of love it in retrospect. It’s definitely better than The Stand.

Tower-wise, Insomnia is hard to pin down. By the end of the novel, it is practically a Dark Tower story in itself. It has a significant connection to the last book in the series. In fact, King explicitly calls attention to Insomnia as a major part of the Dark Tower mythos in the final volume, only to dismiss it mere pages later. It’s a moment so weird that it will probably make you want to read Insomnia regardless when you get there. It also takes place in Derry, Maine. So: if you’re a Dark Tower fan and an It fan, Insomnia is absolutely essential.

Hearts in Atlantis

Placement: After Wizard and Glass (book 4)

Excellence: 9

Tower-relevance: 10

Listen: I believe that all of the books I’m listing here will significantly improve your experience reading the later Dark Tower novels. But there are two that are absolutely critical. Hearts in Atlantis is one of them. You should rejoice at this, because aside from being essential Dark Tower prep, it is also one of the most glorious books in King’s whole catalogue. It is a collection of novellas, some better than others. My personal favourite is the titular novella (Tower-relevance: 0), but the main event for our purposes is “Low Men in Yellow Coats,” also one of King’s finest stories.

“Low Men” is neither fish nor fowl: a literary story that’s self-contained for much of its duration, until it becomes so inextricably tied to the Dark Tower that it couldn’t possibly resonate for readers who aren’t caught up. The good news is, as a Tower reader, you are perfectly positioned to experience one of the most beautiful endings ever written by a guy who’s bad at endings.

Hearts in Atlantis as a whole reckons with the legacy of the 1960s: the broken dreams and self-importance of King’s generation. It is the great boomer novelist tackling the great boomer subject. That in itself is relevant to the Dark Tower, whose characters come from throughout time, and whose values reflect the times they come from, ‘60s counterculture included. More concretely, the events of “Low Men in Yellow Coats” are directly important to the final Dark Tower novel.

Everything’s Eventual

Placement: After Wizard and Glass (book 4)

Excellence: 5

Tower-relevance: 6

I’m going to do you a favour here. You don’t need to read all of this one. It is perhaps King’s least acclaimed short story collection, though it’s also the only one I’ve read. The only story in it that I truly loved was “Lunch at the Gotham Café” (Tower-relevance: 0), and there are only two stories in it that pertain to the Dark Tower at all.

One, “The Little Sisters of Eluria” is a straight-up Dark Tower story, featuring the series’ protagonist Roland of Gilead shortly before the events of The Gunslinger. The other, the title story, deals with a character who will unexpectedly reappear in a Dark Tower Extended Universe supergroup of sorts, about midway through the final Dark Tower novel. (Hardly a spoiler – what could he possibly be doing there?)

My advice is simply to read those two stories (and “Gotham,” just for fun) and leave the others aside. They’re only worth your time if you’re “in for a penny” and you’re a pretty fast reader.

‘Salem’s Lot

Placement: After Wizard and Glass (book 4)

Excellence: 8

Tower-relevance: 10

The two most essential Dark Tower-related books are Hearts in Atlantis and ‘Salem’s Lot. In particular, reading Wolves of the Calla without having read ‘Salem would be like skipping a book in the series. Good news, though: ‘Salem’s Lot is really good. It’s arguably the novel where King becomes King, jettisoning the tight focus of Carrie in favour of a massive, town-spanning cast and a powerful sense of place.

Here is a spoiler that you’d also encounter on the book jacket of any of the last three Dark Tower novels: ‘Salem’s breakout character Father Callahan is a central character in the Tower saga, from Wolves of the Calla onward. Wolves is as much a sequel to ‘Salem’s Lot as it is to the previous Dark Tower books. It is almost comically essential. There should be a warning sticker on every copy of Wolves, warning readers off unless they’ve got the pre-requisites. At least this one.

And that’s it! Having read all of these books (or at the very least: Hearts in Atlantis, ‘Salem’s Lot, and the relevant stories in Everything’s Eventual), you’re totally prepared to barrel forward through the last three books in the Dark Tower series, and love them as much as I do. To that point:

Part Two: The Dark Tower, ranked

8. The Wind Through the Keyhole (Book 8, or 4.5)

King’s return to the world of the Dark Tower seven years after it had officially finished is a perfectly entertaining book. But of the three stories here, nested inside each other like Russian dolls, only the innermost one feels totally committed. It’s a sort of fairytale that’s told as a bedtime story within the fiction of the Dark Tower, but the suggestion is that it’s also something that definitely actually happened.

The story’s outer layers deal explicitly with the story of Roland and his various sidekicks throughout his long life, but they’re really mostly interesting to bring out resonances in the inner story, which has nothing explicit to do with that set of characters.

Some people recommend reading this book after Wizard and Glass, which is where its events take place within the series’ continuity. Don’t do that. This book is an afterthought, and should be read accordingly.

7. Wizard and Glass (Book 4)

Easily the most contentious book in the series, some consider it the best of all and one of the best things King ever wrote, and others see it as a needless diversion from the main thrust of the story. To be clear, it’s my least favourite of the main series by a wide margin, but I don’t really understand what’s to hate about diverging from the main story as such – if you’re looking for ruthless narrative efficiency, you’re reading the wrong series. You’re reading the wrong author.

Still, Wizard and Glass is a huge slog. Like The Wind Through the Keyhole, it is presented mainly in flashback. The flashback that makes up the bulk of the novel is primarily a love story, one that establishes the causes of certain tendencies in our hero. The best thing about it is its setting: a town whose geography and characters become familiar by the end. (King has done this before, more successfully, outside of this series – and he’ll do it again within the series, to much stronger results.)

The worst thing about it is the love story. Roland’s love interest, Susan, is an extremely central point-of-view character, with an extremely underdeveloped point of view. Many readers disagree. Fair enough. I didn’t hate Wizard and Glass, but hearing that it’s some people’s favourite makes me feel like I read a different book.

6. The Drawing of the Three (Book 2)

To be clear: everything from here on is aces, in my opinion. I say that, because this is one of the most acclaimed books in the series, and I’m placing it lower than some less beloved installments. The Drawing of the Three is in many ways where the story of the Dark Tower really begins, where Roland meets the supporting cast that will define the rest of the series. It’s also where the multiverse spins up, such that the book is almost more like three novellas than like a single novel, each in its own time and place.

These novellas are of dramatically different quality. The first and best of them is a crime thriller that’s as much of a page turner as anything King has ever written. The others are more mixed, and the introduction of a Black character named Odetta Holmes – overall, one of the best characters in the series – rankles. King is… let’s call him a problematic boomer antiracist. He’s really trying here, and he almost gets to something interesting about stereotypes of Black people in fiction. It doesn’t really land.

Drawing still rips. The frame narrative connecting the three novellas is one of the best drivers of tension King’s ever devised.

5. Song of Susannah (Book 6)

This is the one that’s supposed to be at the bottom. And here I am debating whether I should maybe put it one slot closer to the top. Granted, it isn’t perfect. The last three books of the Dark Tower series are a trilogy in themselves, and Song of Susannah has some traits of the neglected middle child. The main characters are split up between plotlines. Some of them are absent for nearly four hundred pages. Where most of the other books in the series have a distinct story of their own, a lot of this one is table setting for the final volume.

But as table setting goes, it’s pretty enthralling. It is the book where the series’ intertextual tendencies finally pays off. And it is a wild ride for its title character, who endures one of the most imaginative horrors King has ever devised.

Again, no spoilers: but there is one thing that happens in this book that makes some readers specifically angry: a metafictional turn reminiscent of Breakfast of Champions, Adaptation, and stories by Borges and Calvino. I’m not sure that this thing I’m talking about works as well here as in those other examples. But if you’ve spent thousands of pages in this writer’s company and when this thing happens you aren’t at least interested to see how he handles it, I dunno what’s wrong with you.

4. The Waste Lands (Book 3)

The closest the series has to a consensus masterpiece, The Waste Lands is our first opportunity to spend time with our whole supporting cast, together. It’s also the book where Roland travels through the largest swathe of his fictional world. Many of the other books move frequently from one reality to another, or else simply focus on one key location. The Waste Lands is unique in that it takes place mostly in Roland’s own reality, and it’s a travel-heavy story. There’s no better book in the series for delivering a sense of the vastness of this world.

It’s also where the best supporting character in these books, Jake Chambers, becomes a series regular.

And it’s got an evil pink monorail who speaks in all caps. It’s really no wonder people love this one.

3. The Gunslinger (Book 1)

If you take as long as I did to read the Dark Tower series and its various related novels, you might forget by the end of the process how wildly different the first novel is in tone from anything that came after. (This is easily rectified by re-reading it immediately after you finish book seven, which I highly recommend.) King started writing The Gunslinger in his early twenties, and it reads like a book written by an author with Very Serious Literary Aspirations. In particular, it reads like Blood Meridian, but if Blood Meridian were kind of dumb (complimentary).

King revised the book after finishing the series, in a fashion now frowned upon in a world blighted by George Lucas’ “special editions.” The revised book now contains references to elements of Dark Tower continuity that King hadn’t devised at the time of the novel’s original composition, and even alters the text to suggest the story’s ultimate ending in a way that the original version did not. It also contains occasional incursions of in-universe colloquial speech like “tell ya sorry” that don’t become prominent until much later. Reading the revised Gunslinger first, then proceeding throughout the rest of the series causes the disorienting experience of these linguistic tics existing, vanishing for three whole books, then returning suddenly for their actual invention in Wolves of the Calla.

Still, King wisely left some of The Gunslinger’s most unresolvable questions open. The novel’s most beguiling ambiguities remain unreconciled to such an extent that if you choose to reread it (even its revised version) after completing the series, you may well find it more baffling than before, not less. Neither of The Gunslinger’s two texts is ideal (I have sampled the original text by way of an old audiobook you might find floating around). But their inconsistencies speak to King’s process in a way that, to me, enriches it. The Gunslinger was, and remains, a bizarre outlier. It’s a great novel, whether its author knows it or not.

2. The Dark Tower (Book 7)

The final book in the series is gargantuan and reluctant. At least the first three quarters of it have the sense of a chain of dominoes falling: everything you knew had to happen does, usually in a wonderfully unexpected way. Then, it suddenly slows down dramatically, as if King is unwilling to face the actual end of a story he’s been struggling to tell for thirty years.

The story ends in, to me, the only way it possibly could. I’m aware some readers dislike it. I simply don’t understand that. Forgive my vagueness, reader who in theory hasn’t read this book yet, but the final ending of the Dark Tower series is not the sort of thing you can call “good” or “bad.” It’s simply necessary that it is exactly what it is.

All of this is entirely beside the point: The Dark Tower is over 1000 pages of incredible shit that brings thousands and thousands more pages of King’s writing to a head. It’s as good as King gets.

1. Wolves of the Calla (Book 5)

A lot of what happens in the Dark Tower series has an air of inevitability. King goes on about the concept of “ka,” which essentially means “destiny.” The prevalence of that idea in these books makes for a lot of moments when a wild plot contrivance is simply deemed inevitable. It also means that things frequently happen exactly as you would expect, without any attempt at a last-minute plot twist or reversal of fortune.

Nothing feels more inevitable than the moment when this wild west-inspired intertextual epic simply turns into The Magnificent Seven. It was bound to happen.

The thing that’s great about The Magnificent Seven – and even better in its source material, Seven Samurai – is how it takes its sweet time getting to the fireworks factory. Both movies spend the bulk of their running time establishing the texture of their settings, making you care about the towns where they take place and establishing the stakes of the final action sequence. Even putting iconography aside, this is extremely compatible with the whole sensibility of the Dark Tower. I can think of no other story that’s more committed to atmosphere over plot, and I’m sure Akira Kurosawa would approve of King’s love for a melancholy anticlimax.

The town where Wolves of the Calla takes place is the most compelling single location in this whole series, filled with believable characters and weird little rituals. Overall, quite a lot happens in Wolves of the Calla, but not in the same way that a lot happens in The Drawing of the Three. A lot happens in the same way that a lot might happen in a year of your actual life. It’s a wild genre fiction with the texture and pace of lived experience: a theme park in book form. I’m not sure I’ll ever read the full Dark Tower series again, but I am quite certain I want to revisit Wolves of the Calla, which is maybe second only to It – another masterpiece of small-town atmosphere – in my overall ranking of King’s books.

And, I mean, it’s also got a vampire-slaying, multidimensional priest from a book King wrote almost thirty years before. How anybody couldn’t love this is beyond me.