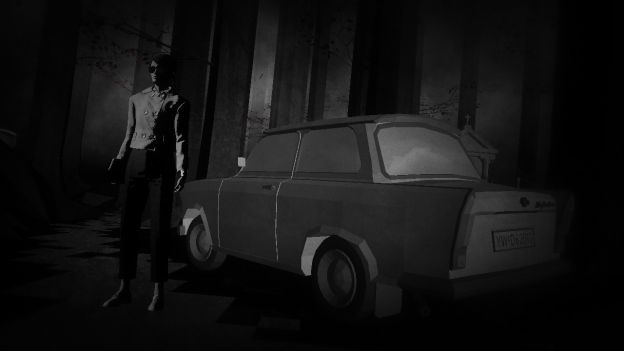

We select “New game” from the title menu, and we immediately find ourselves lost in the woods. We have no clear idea of who or where we are, or what we’re meant to do.

Better get our bearings.

Nostalgia Figurines $1

Lorelei and the Laser Eyes is unlike anything else the developer Simogo has ever made, and at the same time it is explicitly linked to everything they’ve ever made. I would know. This post is intended to work as a standalone piece, but it is also the fourth and final part of a retrospective on Simogo’s complete works. If you’d like to read from the beginning, you’ll find it here. I have spent a good chunk of the nine or so months since Lorelei’s release replaying Simogo’s whole catalogue, tracing common themes from one game to the next, and discovering the general shape of their body of work.

In my view, Lorelei is the second game in an intentionally backwards-looking phase of their career, forming a pair of “secret sequels” with Sayonara Wild Hearts. Here’s my schematic in brief:

They started with a trilogy of casual mobile games…

- Kosmo Spin

- Bumpy Road

- Beat Sneak Bandit

…continued with a second trilogy of metafiction-inclined adventure games…

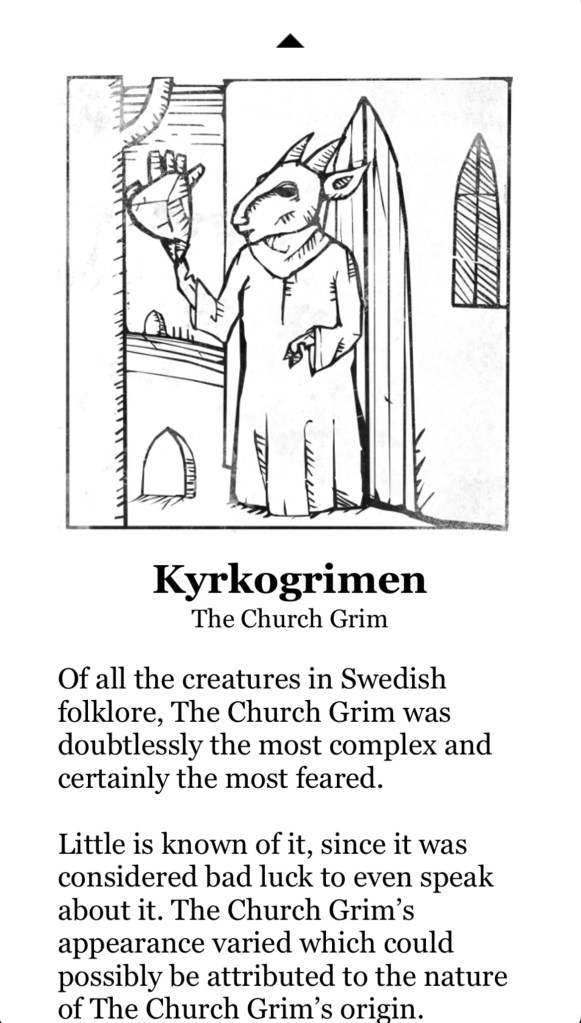

- Year Walk

- DEVICE 6

- The Sailor’s Dream

…took a beat for an “intermission featurette” containing two small and contrasting works…

- The Sensational December Machine

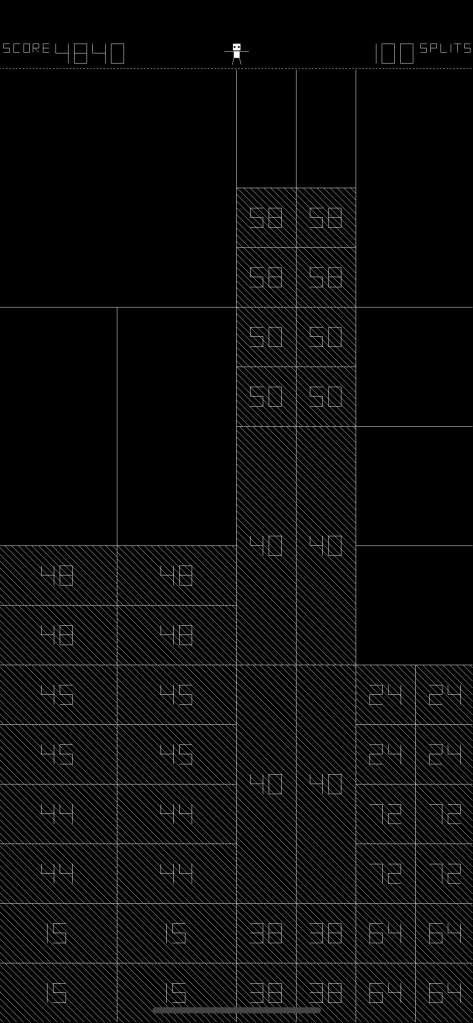

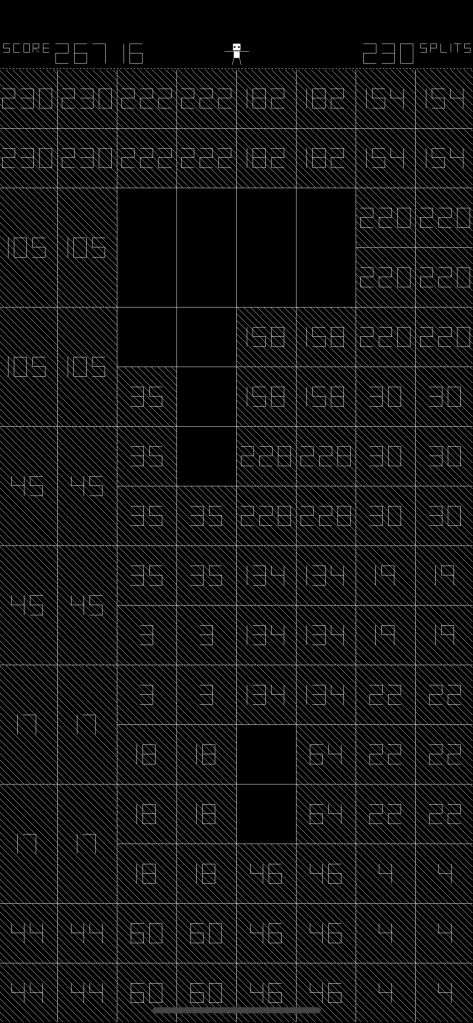

- SPL-T

…and most recently, they’ve created two ambitious games that each recall a different past phase of Simogo’s career…

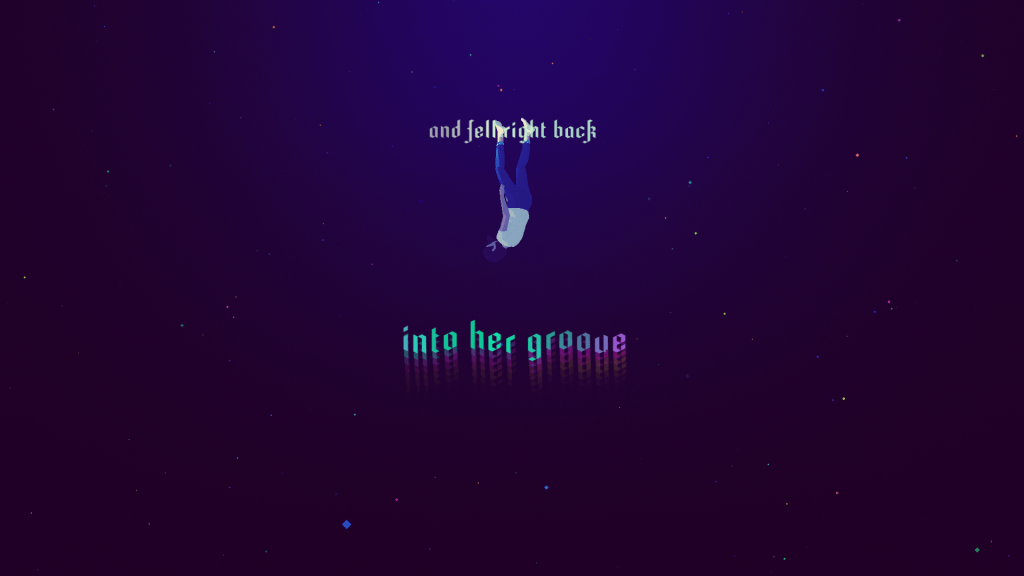

- Sayonara Wild Hearts, a secret sequel to their early trilogy of casual games

- Lorelei and the Laser Eyes, a secret sequel to their second trilogy of metafiction adventures.

If this schematic continues to its logical conclusion, then Simogo’s next game will have to be a meditation on the trilogy that it is itself a part of: a secret sequel to Sayonara Wild Hearts, to Lorelei and the Laser Eyes, and–somehow–to itself. In practice, this would be ridiculous, not because it’s impossible but because Simogo has already made that game. It’s this one.

Lorelei and the Laser Eyes shares most of its DNA with Simogo’s second trilogy, particularly DEVICE 6, which is also a midcentury-inspired adventure through a labyrinthine property littered with escape room puzzles and enigmatic men in suits. But its explicit references to Simogo’s back catalogue go back well beyond Year Walk, encompassing their early casual games and even their pre-Simogo work ilomilo. It sequelizes the whole of Simogo’s corpus. And if any game is recursive enough to be considered its own sequel, it’s either The Stanley Parable: Ultra Deluxe or it’s this.

Lorelei’s dialogue with its predecessors begins in literally the first frame, with a car named “Lily Christine,” a reference to a rowboat in The Sailor’s Dream. The car’s license plate number, YW-D6-2013, completes the trilogy, referring to Year Walk, DEVICE 6, and the year of their release. Get in the car and turn on the radio, and you’ll find the jockeys playing old hits like the final boss music from Beat Sneak Bandit. This is not hidden. Before the game reveals anything about itself, it allows you a trip down a memory lane full of memories you might not actually have.

Knowledge of Simogo’s catalogue is by no means plot critical to Lorelei. But for those of us who’ve scrutinized the complete works, there are more than just Easter eggs here: there is a continuity of purpose, an explicit attempt to frame their work as a tidy series of related gestures that, for better or worse, culminate here. Whatever else it is, Lorelei and the Laser Eyes is a self-curated Simogo retrospective. And why shouldn’t it be? We’ll soon discover that this is a story about artists seeking to give shape and meaning to their own pasts. It may or may not be self-indulgent, but it’s all of a piece.

If you’ve read the first three parts in this series, you may be expecting a fairly holistic analysis of this game, which is what I attempted to bring to each of Simogo’s other games. That won’t be possible here. The most obvious difference between Lorelei and the Laser Eyes and its predecessors is that it is comparatively gigantic. You can have a relatively complete experience with any of Simogo’s other games in one or two sittings. Lorelei has a 17- to 24-hour campaign, with the strong possibility that it will take even longer if you’re a Smell The Roses type player. If I’m going to say anything meaningful about this sprawling work, I’ll have to limit my scope.

(Full spoilers, nevertheless.)

In certain creative works, you can hear the creators asking themselves a question. Having played through everything Simogo has ever made, and having now finished Lorelei twice, the question I hear in this game is: who do we make things for?

This is not a simple question. At any given time, the answer could be: for ourselves, for the publisher, for the critics, for the general public, for a niche community of self-identifying “gamers,” or for people who are specifically invested in Simogo games in particular. I haven’t spoken to anybody involved in the creation of Lorelei, but I feel that the game itself announces its intent to grapple with this question, trying on different responses for size. This game is a treasure hunt for self-awareness, not just on the player’s part, but (I suspect) on the artists’ parts as well. It is an act of stock taking: an explicit attempt to address a question that has implicitly defined Simogo’s output for fifteen years.

So. Who is Lorelei and the Laser Eyes actually for?

Directional input… any button…

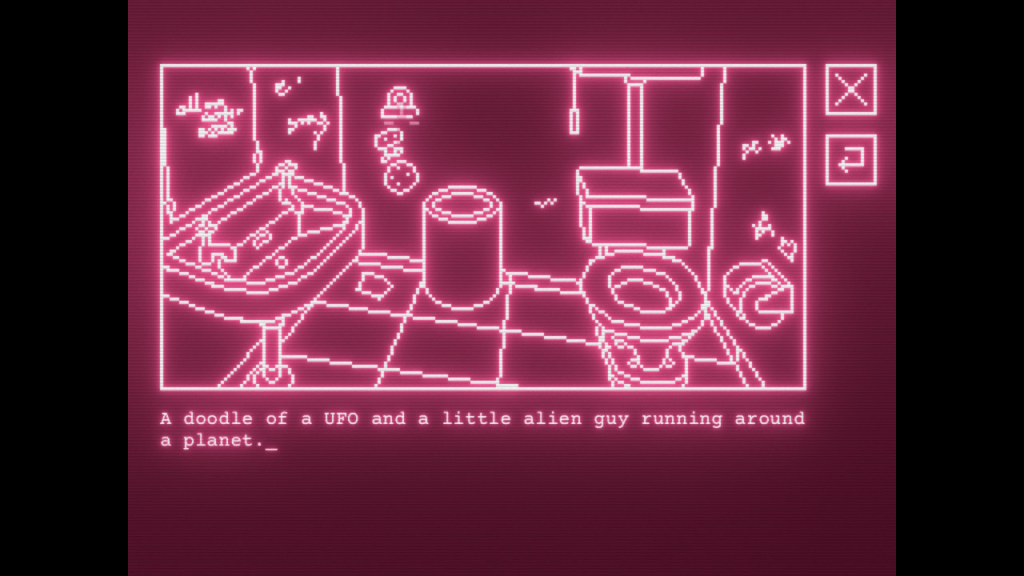

The single most prevalent complaint in Lorelei’s broadly positive reviews was about its control scheme. As Griffin McElroy put it: “In this game, you can move around, and then you have button.” Which is to say, there are only two inputs in Lorelei: a single directional input, and an action button. Several action buttons, really. In the Switch version, all of the main gameplay buttons on the controller are interchangeable. The action buttons–all of them–double as the button that pulls up the menu when the player character isn’t standing near an interactable object. Odder still, while you’re in the menu, if you want to retreat to the previous submenu, there’s no dedicated button for that. Instead, you’ve got to navigate to the “x” icon in the corner of the screen.

The fact that this extremely small UI issue came up in so many reviews, positive or not, indicates just how annoying it is. There is a widely agreed-upon, better way to do this: the A button is for selecting things; the B button is for going back. It’s so prevalent, and so ingrained in the muscle memory of anybody who’s ever owned a console or handheld, that it feels odd to even describe it. Lorelei’s lack of a back button makes you feel like you’re writing with your non-dominant hand. It causes an effortless task to become effortful.

But to whom is the task effortless? Again: to anybody who’s ever owned a console or handheld. What about everybody else? Historically, this is one of the main questions that Simogo has sought to answer. They started their career in the primordial days of “casual games” for mobile phones. And since then, they’ve been more committed than almost any other game developer to questioning the assumptions of what a player will come to a game already knowing. Simogo made a name for themselves by creating thoughtful and immersive games that required no more explanation than a web browser. Reducing the barrier to entry has traditionally been part of their core mission.

In theory, Lorelei’s control scheme is simpler than the standard one. The “move around, and button” approach keeps you from having to think about what button to press. But, unlike with Year Walk, DEVICE 6, The Sailor’s Dream or even Sayonara Wild Hearts, I find it hard to imagine that much of this game’s potential audience would see the benefit of this ostensible simplicity. For one thing, it is Simogo’s first game not to be released on mobile devices. For the first time in their history, Simogo is selling a product exclusively through video game shopfronts like Steam and the Nintendo eShop, making it unlikely that players who aren’t predisposed towards games will encounter it at all.

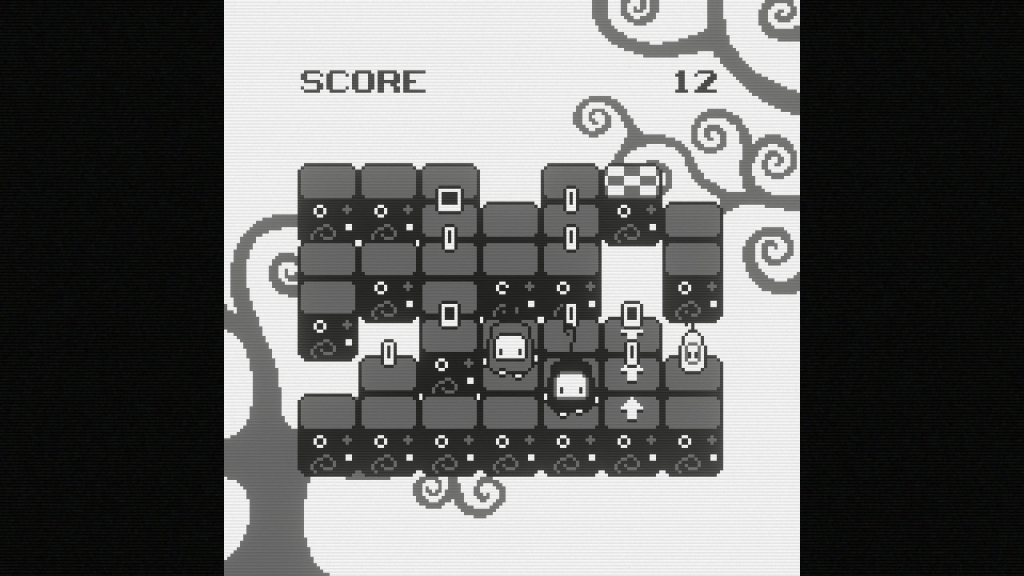

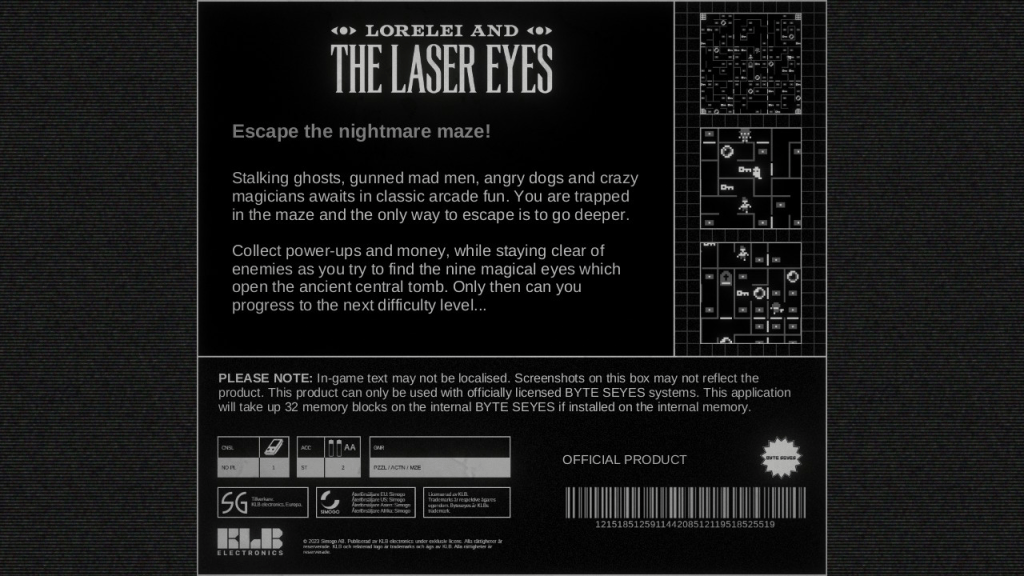

But more puzzlingly, Lorelei and the Laser Eyes is a video games-ass video game, filled not only with references to Simogo’s own back catalogue, but to the culture and heritage of video games in general. With their previous release, Sayonara Wild Hearts, Simogo’s stated aim was to finally create a video game that was “unashamed of being a video game.” Lorelei goes much further in this direction, incorporating references to the Game Boy, to the cheat codes you could sometimes input via secret controller inputs on vintage consoles, and to the physical ephemera of retrogaming. On three separate occasions, it forces you to use fucking tank controls.

It feels like Simogo is being pulled in two directions. On the one hand, they maintain their impulse to keep the controls simple for the benefit of the broadest possible audience. But on the other hand, they’ve filled Lorelei with old-school gamer shibboleths. Lorelei is neither fish nor fowl. Maybe the only way to make sense of it is to take it for what it aggressively asserts itself to be: a Simogo game. The Simogo game. The game where Simogo lays all of their principles and fascinations on the table for the enthusiasts to puzzle through.

INVESTIGATION REPORT

Before we move on, it’s probably worth discussing what actually transpires in Lorelei and the Laser Eyes, as I understand it. The game takes place in a grand old hotel containing a frankly decadent variety of locked doors. As we unlock those doors, we gradually learn the identities of four key players in the story.

Our player character is Lorelei Weiss, a conceptual artist whose work made trailblazing use of computers in the early 1960s. We’re told that her early drawings prefigured the polygonal wireframes of 3D animation. One of Weiss’s most notable works was a collection of puzzle boxes, inviting the viewer to participate in unlocking them. So essentially, Lorelei Weiss is a game dev: an authorial insert on behalf of any or all of the artists who created this game.

The two most obvious answers to the question “who do we make things for” are “the audience” and “ourselves.” If we’re ever tempted into thinking that those two answers are mutually exclusive, we should remember that the player’s avatar in this game is also an authorial insert. It’s never simple.

Next up, the man we came to see:

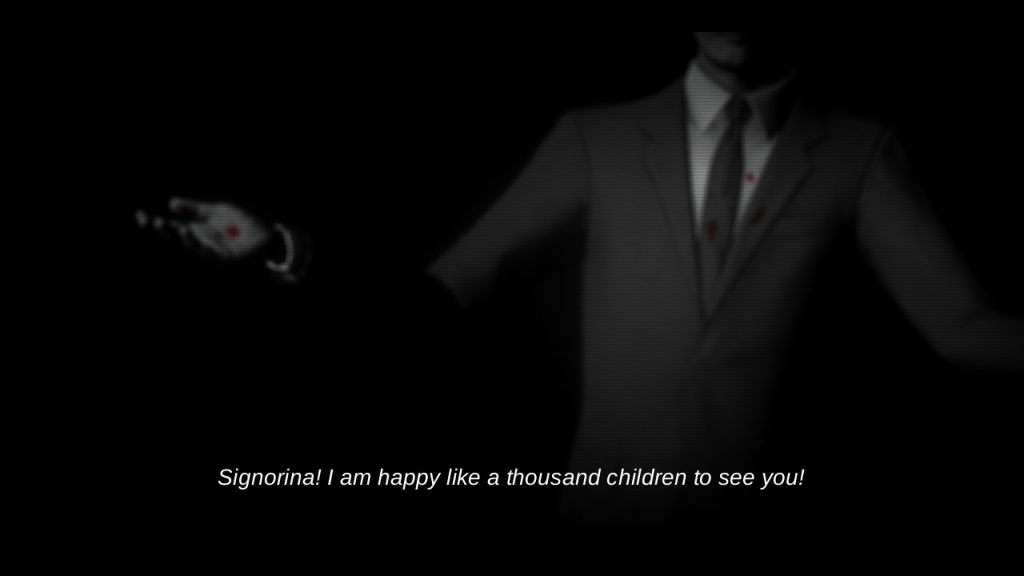

Renzo Nero is a filmmaker who’s summoned us to the hotel to assist him with a project he refuses to describe. Renzo talks in half-meaningless aphorisms that he seems to have made up on the spot. We learn more about him as we collect documents scattered around the hotel. He’s a fearsomely divisive figure in the film world: a provocateur with a gambling problem, a penchant for mysticism, and a dictatorial streak. He courts controversy by saying dumb shit, like that the atomic bomb was beautiful. (I’m reminded of Karlheinz Stockhausen calling 9/11 “the greatest work of art imaginable for the whole cosmos.”) He is every inch the Problematic Art Man of a prior generation, but perhaps it’s all bluster.

Notably, for almost the entire game, we only see him from the nose down. The same is true, for hysterically obvious reasons, of our next player:

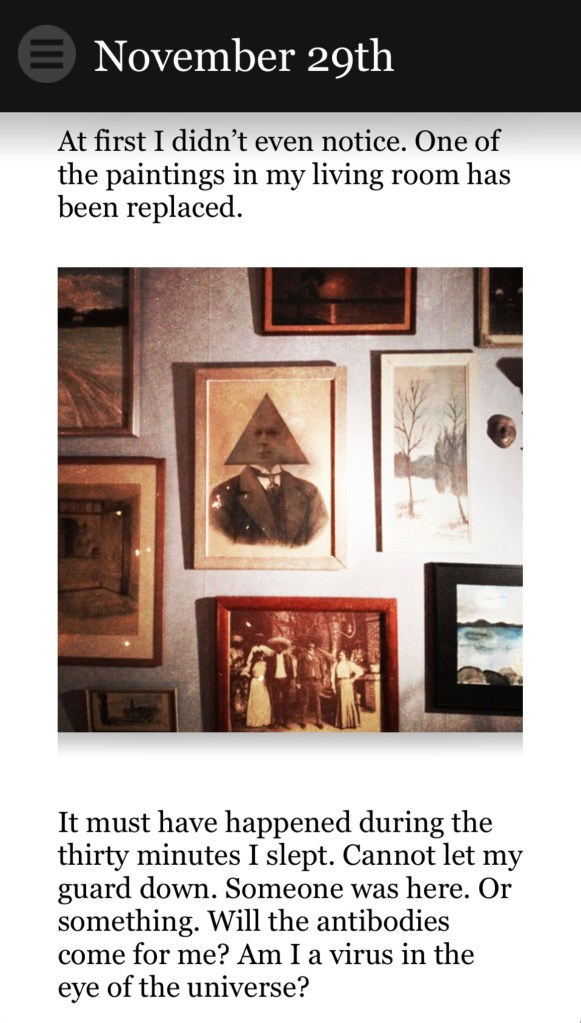

This guy is in fact not nameless; he is Lorenzo the Great, an old-timey stage magician who is transparently just Renzo in disguise. But that is not all he is. We hear stories about Lorenzo, that place him at a far earlier time in history to the mid-20th century when Renzo supposedly lived. And he communicates with us through uncanny means: letters placed beside safes that contain floppy disks, and then through messages hidden within those disks. There are posters of him scattered throughout the hotel, each adorned with a mysterious red rune.

And finally:

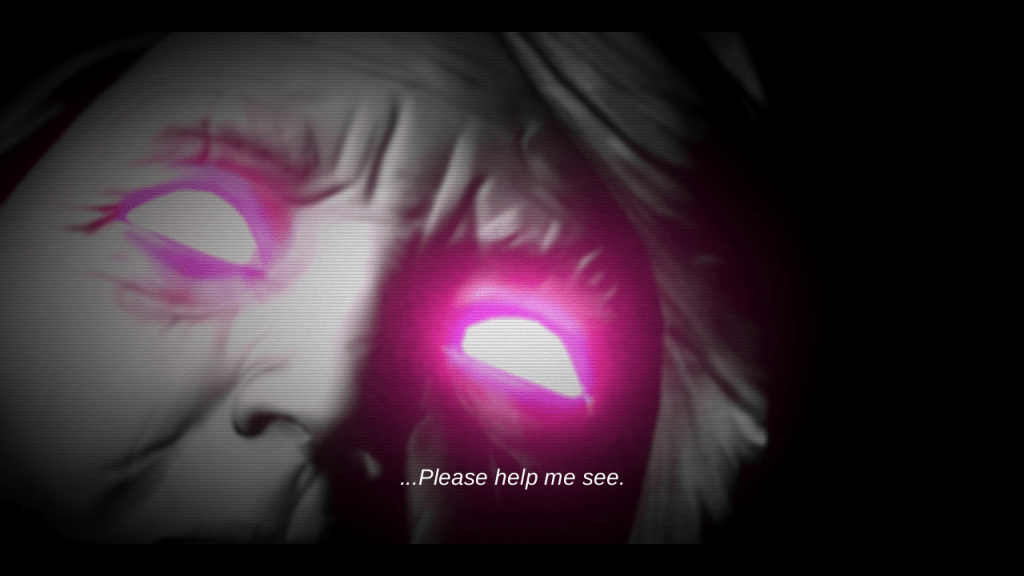

This woman appears in three forms across the hotel grounds. There’s this eyeless ghost, floating outside a broken third-floor window. There’s the conspicuous corpse lying on the ground directly below that broken third-floor window. And there’s a young girl wearing an owl mask. It isn’t obvious from the start that this girl is related to the woman, but the more we see her the more she suggests this. It’s nice of her to be so direct. She is in fact the most helpful person around–unsurprising, since the instructions explicitly told us: “Listen very carefully if a person wearing an owl mask speaks.” She is this game’s Kaepora Gaebora: a quest giver, who imparts information as plainly as Lorelei’s idiom allows.

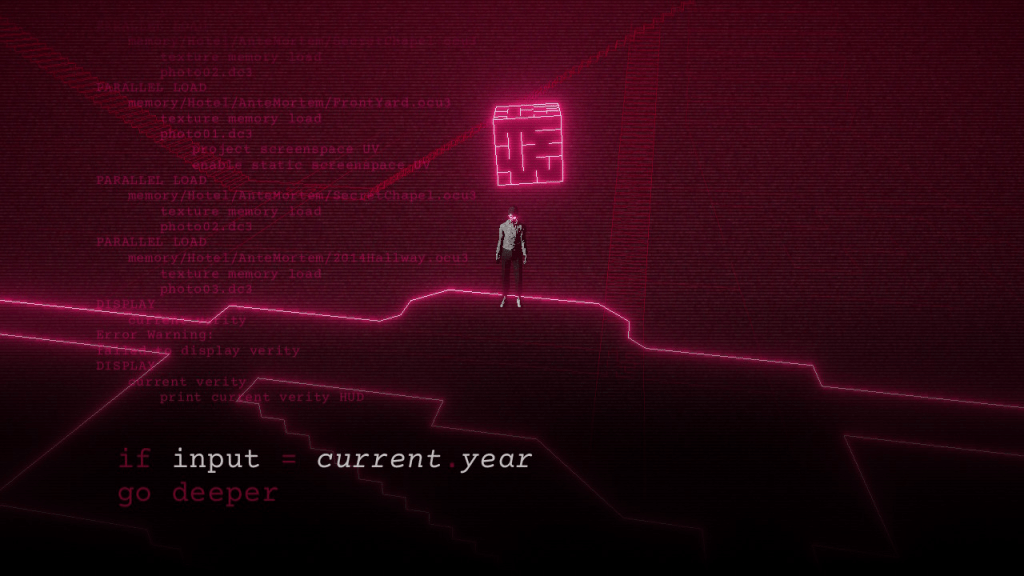

The woman’s name is Renate Schwarzwald, and she was ostensibly the owner of this estate before it became a hotel. Like our other characters, she is an artist: a portraitist whose eyes failed in later life, leading her to embrace abstraction–not unlike Sargy Mann. Schwarzwald’s late work gives Lorelei its most indelible image: a man in a black suit with a neon red maze for a head. Identity is a puzzle in this game. Faces are obscured by coy camera angles, blurry textures, and sunglasses. Schwarzwald’s maze man–a creative insight born from a lack of literal vision–hits the nail on the head.

Schwarzwald isn’t the only character here who appears in multiple instances. When we find our way into our hotel room, we discover that we’re already there:

This old woman with glowing red eyes is Lorelei Weiss, our player character, decades later, ohne sunglasses. That fact is not immediately obvious: in my view, the narrative purpose of the player character’s sunglasses is to mask whether she has glowing red eyes or no eyes at all, i.e. whether she is actually Lorelei or Renate. Until close to the end, the game is very keen on allowing its characters to crisscross into each other’s identity space.

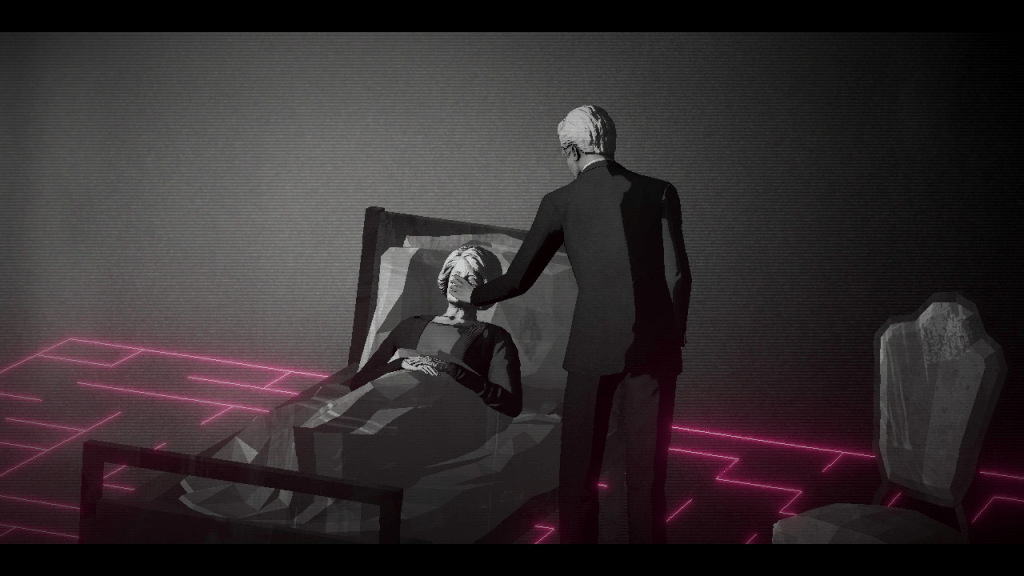

But by the end, it’s obvious that this elderly woman represents the most empirically “real” thing in this whole godforsaken hotel. It is not actually the middle of the 20th century; it is 2014. We are not actually in the Hotel Letztes Jahr; we are in the Schöner Tag care home, coping with dementia. What we have been experiencing in this game is a difficult journey through Lorelei’s heavily barricaded memory palace. The people we’ve been talking to are two-thirds fictional: Renate Schwarzwald and Lorenzo the Great are characters in an unmade film by Renzo Nero. Renzo himself was an old colleague of Lorelei’s. He invited her to collaborate with him in 1963, but fell into a deep mental illness before the project was complete.

The reason we haven’t seen Renzo’s eyes yet is because he gouged them out. In this state, he threatened Lorelei, who pushed him through a window in self-defense: an inversion of the ending of Renzo’s unmade film, where it’s Renate who’s pushed through a window by Lorenzo the Great.

It’s a clean and decisive ending–possibly a disappointing one for those of us who appreciate ambiguity. “It was all in her head” is not the sort of ending a creative writing professor would sanction. But there’s more to it than that. At the end of my second playthrough, the facet of the ending that really hit home for me was Lorelei’s reconciliation with Renzo. Clearly, she feels guilty for her part in his death. And obviously her memories of Renzo are coloured by the fact that she knew him at his worst. But the image of Renzo that the game leaves us with is not of him with bloodied eye sockets, or even with his face cut off at the nose. Rather, we see him in full, looking youthful: a comforting presence for the dying Lorelei.

My favourite single moment in Lorelei is a sequence during which Renzo and Lorelei dance the bossa nova. Renzo’s interests are “not amorous”–he’s gay. Rather, he insists on dancing with every collaborator before a project. That way, when things get heated, “we know that once we danced together.” Much of what transpires in Lorelei’s memory palace cannot possibly be literal memory. But I take this scene to be an actual recollection of something that happened before Renzo took a turn for the worse: a fond memory of Renzo at his most charming, wily and beguiling. Keeping this scene in mind, the ending is less about the reveal that “it was all in her head” than about one final character beat. For decades, Renzo has lived in Lorelei’s head as a source of trauma: now she remembers the whole person.

Cinema does not need people to exist

Back to our central question: who is Lorelei and the Laser Eyes for? Another possible answer is: cinephiles.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I’d been following what little news there was about Lorelei very intently during its development. To me, the single most exciting announcement was that Simogo was working on something inspired by Alain Resnais’ 1961 film Last Year at Marienbad. I wasn’t excited because I love the film overall (I don’t), but rather because Resnais’ specific triumph is a triumph of atmosphere. Marienbad is a film that gets enormous mileage out of the sheer, undeniable mood of its opulent setting–a hotel, no less. (Other films like this include Casablanca and Spirited Away.) It is a film that makes you want to live inside of it, however eerie and unsettling that experience might be. Lorelei and the Laser Eyes fulfills a dream I didn’t know I had: Last Year at Marienbad, but make it Resident Evil 1. (The dramatic central staircase could be a reference to either.)

Last Year in Marienbad is the most explicit cinematic influence on Lorelei (the neon sign reading “Hotel Letztes Jahr” is visible from the woods you start the game in). But it’s hardly the only one. If you’re obsessed with this period, you’ll probably detect a hint of Persona or Performance in the identity slippage that occurs throughout the game. If you’re obsessed with David Lynch, you’ll find it impossible to imagine Lorelei without him: a pioneer of the boundary between the real and the unreal–and a connoisseur of the colours black, white, and red.

But the cinematic influence that has the most to do with the question of “who is this for?” is Federico Fellini’s 8½. This is another film mentioned in Simogo’s initial announcement. Like Lorelei, the film is concerned with the creative process. It is a film about filmmaking, with a filmmaker at its centre in the same way that Lorelei centres on a prototypical game developer. Renzo bears a slight resemblance to Guido Anselmi, 8½’s protagonist, and they share a profession. But it’s Lorelei Weiss who’s inherited his taciturn cool, his tendency towards autobiographical art, his position as an authorial insert, and his extremely rad shades.

Like Lorelei and the Laser Eyes, 8½ is an act of autocritique. If we continue to take Lorelei as a hunt for self-awareness and an act of stock taking, then it is very much in the tradition of 8½. Fellini’s film is self-referential, almost to the point of smugness. It is named for its position in Fellini’s filmography. Close to the start of the film, we learn that Guido has hired a film critic to help him flesh out the screenplay he’s struggling with. Predictably, he’s of no help whatsoever. He spends the film manifesting Guido’s (and possibly Fellini’s) inner critic, saying things like “you need a much higher degree of culture.” There’s also a producer stomping around, looking after the bottom line, telling Guido: “How could you not care if audiences understand? I’m sorry, but that is arrogant and presumptuous.” It’s hard to know whether Guido, or Fellini, agrees.

If 8½ is going to resonate with you, you’ve got to be onboard for this kind of talk, where the big questions about the relationship of artists, their art, and their audience are debated in plain language. The same goes for Lorelei and the Laser Eyes, which approaches the same themes in precisely the same register of near self-parody. Both the film and the game put themselves at risk of smugness by preemptively ridiculing their critics and suggesting that we, the audience, might not be all that important. And in both cases, the sincerity of these claims is a matter of interpretation.

In Lorelei, it’s the filmmaker who makes the Big Proclamations. Renzo Nero’s personal manifesto is the most direct statement in the game on the question “who do we make things for?” Like the dialogue of the critic and the producer in 8½, it’s not necessarily sincere–but it might be disagreeable all the same, for readers who prefer a subtler approach:

Renzo spends the game inveighing against any external force that threatens his singular vision. To Renzo, there is nothing more important than a singular vision. That’s what attracted him to Lorelei as a collaborator in the first place: she has laser eyes. During their cathartic pre-production bossa nova, Renzo assures Lorelei that their project will “overthrow the industrial entertainment complex,” rendering art and commerce separate at last. Renzo reviles his funders, his critics and his audience. He seeks to be free of them all, free to make a parodically extreme form of “art for art’s sake.” In the end, he deems even his own eyes to be a threat to his work, and removes them so he might inherit the visionary capacity of Renate Schwarzwald, his blind creation.

“How could you not care if audiences understand?” asks the producer in 8½. “I’m sorry, but that is arrogant and presumptuous.” If Renzo could bear to use an expression he didn’t personally coin, he might respond: “hold my beer.”

An old artist who looked into a red mirror

In the same announcement where Simogo namechecked 8½ and Last Year at Marienbad as influences on their upcoming game, they wrote of their concern that “entertainment is dying, perhaps is already dead. Pre-chewed to mean absolutely nothing. Culture as hamburgers to pass time and bring in the dollars.” The message was, after the neon embrace of Sayonara Wild Hearts, the next one would be something difficult. But, they hastened to add: “the interactions and controls should not be the barrier. Everyone should be welcome. An intricate meal should not be hindered by a complicated fork.”

That last line is Simogo in miniature. It is the reason for this game’s stubborn refusal to use more than two inputs, even though that would make it easier for many (probably most) of its players. Simogo’s best work has a Renzo Nero-like singularity of vision, but without his sociopathic disdain for the public. Their games are products of the utopian vision that complex ideas can be made accessible to large audiences. This idea is laughably unpopular today. No politician believes this anymore. It is a lonely hill to die on. One day, in the smoldering aftermath of the culture wars, it’ll stand barren with only a smattering of dead educators, librarians and public broadcasting advocates to indicate that anybody ever cared. It is genuinely cathartic to experience art that takes this notion seriously.

Simogo emerged from a more optimistic time. Barack Obama was president, and the smartphone was poised to democratize access to information. As far as games were concerned, smartphones promised to usher in a new era where games were no longer the province of an insular subculture. Simogo’s early games, drunk on the sheer novelty of the touchscreen, paved the way for a series of adventures that used mobile devices in ever more innovative and always accessible ways.

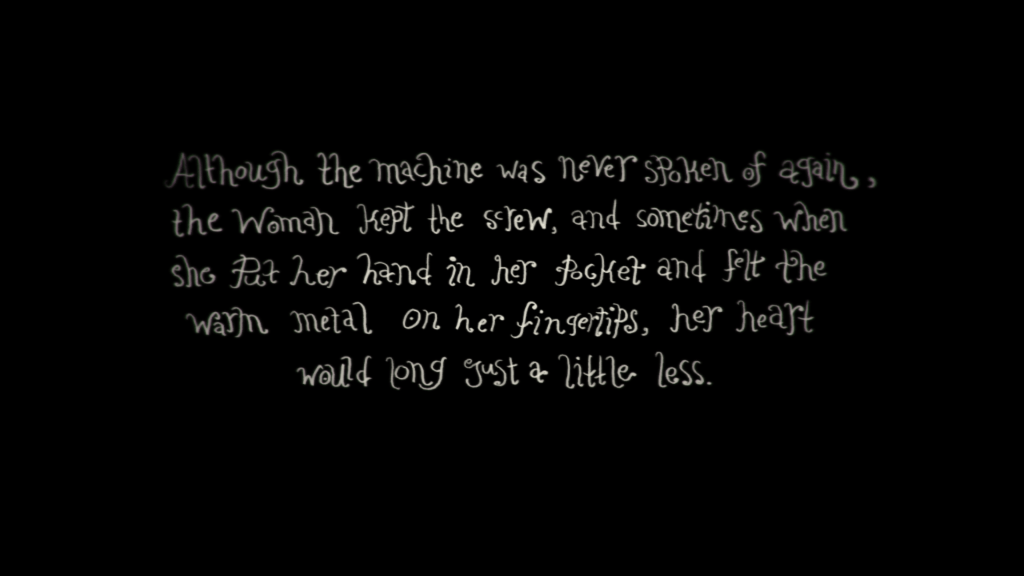

In 2013, we learned just how useful these miraculous new devices were for spying. Simogo responded with DEVICE 6, a game that weaponizes the player’s anxiety about what black magic their phone is capable of. Optimism turned to wariness. The following year, Simogo released The Sailor’s Dream (still their finest work) to weak sales and critical indifference. Instead of publicly succumbing to spite, or forswearing the audience like Renzo Nero, they released The Sensational December Machine. It’s a vanishingly short game that deals with some of the same themes as Lorelei and the Laser Eyes: what it means to make something, and whether it matters what other people think. It concludes that no, it doesn’t necessarily matter. But it does so in the most graceful possible way. Their next major release, Sayonara Wild Hearts, was the definition of a crowd pleaser.

That brings us up to date. The backdrop for this current phase of Simogo’s career is that the era of smartphone pollyannaism is well and truly over. Sayonara was their first game to be released on a console simultaneously with its mobile release, and Lorelei is not available for mobile devices at all. The technology that was once their raison d’etre is no longer viable and has probably made the world worse, so they’ll have to commit to less ubiquitous platforms that cater to a more specialized audience. They’ve experienced success, failure, and compromise. Lorelei and the Laser Eyes is a wild creation whose parts don’t always seem to add up, until suddenly they add up too neatly. But as the culmination of everything Simogo has done before, it could not be more perfect. It strikes me as a reflection of fifteen long years spent constantly thinking about how the audience will respond to something–a howl of frustration at the struggle of making art that welcomes everybody without losing its soul. It is the most melancholy victory lap I’ve ever seen.

To end discussions by giving a “correct answer”

In one version of Lorelei’s story, Renzo has called upon Lorelei to create a maze. “As you know,” he explains, “the maze is a weapon of mass destruction. An endless ride for fascists and critics.” This is Renzo’s trick: he’ll trap us all in a puzzle so that his art remains unblemished by unworthy eyes. That, in a sense, is what Lorelei and the Laser Eyes does as well. It is quite possible to play most of the game, solving puzzles, and not engaging too much with any of the themes I’ve been interested in here.

Then, abruptly, that becomes impossible. The game’s final sequence takes place inside a computer, with code running visibly down the side of the screen. Simogo has always tended to emphasize the softwareness of the software, and for this they deserve an award for the best Verfremdungseffekt of the year. The computer is a manifestation of an ancient force, an artifact called the Third Eye. Think of it as a sort of Train Pulling into a Station for all human creativity.

In this computer, we experience something called the Verity Sequence. We are presented with a series of questions pertaining to the characters in the game. All of the questions have right and wrong answers. We’re expected to know that the old woman and the young woman are both Lorelei. We need to have discovered that Renzo and Lorelei were real people, whereas Lorenzo and Renate were fictional characters. And we need to know that Lorelei was responsible, or feels responsible, for Renzo’s death.

Again, this ending might be disappointing to those of us who appreciate ambiguity. Up until this point, the game has been admirably unwilling to “pre-chew” itself. But a line from 8½ continues to echo through the hallways of the Hotel Letztes Jahr: “How could you not care if audiences understand? I’m sorry, but that is arrogant and presumptuous.”

And so, the Verity Sequence frees us from Renzo’s maze. The fact that the game’s big questions ultimately have unambiguous answers becomes an invitation. We are no longer caught up in the minutiae of puzzle solving, we’re obliged to consider the big picture, and at the last minute we become the person it has all been for.

But remember: all this time, we’ve been walking around as a character who doubles as an authorial insert. We cannot be the only person it’s for. That would be far too simple. Even Renzo, a character who stands for all of the complicated forks and labyrinths of gatekeeping that Simogo disdains, is given grace in the end–because maybe self-indulgence is not a completely useless idea.

In the end, Lorelei and the Laser Eyes is quite simple, and fairly complicated.

And there’s room for everyone.