This is the third part of a retrospective on the complete works of the indie game studio Simogo that begins here. This part will cover The Sensational December Machine, SPL-T, and Sayonara Wild Hearts. Full spoilers, insofar as that applies.

The Sensational December Machine (2014)

Let’s begin by revisiting my broad schematic of the Simogo catalogue. They started with a trilogy of casual games for mobile devices. Next, they made a second trilogy of mobile games focusing on narrative and metafiction. Finally, in my view, their two most recent major releases have served as tacit fourth instalments in each of those trilogies.

The point we’ve now arrived at–late 2014–sits between those latter two phases: after their trilogy of fourth wall-breakers was complete, but before they’d set out on developing their secret sequels. At this point, they’ve shipped six games in the past five years. They deserve a break. Every artist needs a moment now and then to take a breath, to reflect, and to chart a new course. So, between the release of The Sailor’s Dream and the bulk of Sayonara Wild Hearts’ long development period, we get a sort of “intermission featurette”: two small releases that serve as a mirror to the past and a map of the future.

Simogo presented the first of these, The Sensational December Machine, as a Christmas gift to fans. It was a tiny, free, interactive story available through their website–notably not for mobile, but for PC and Mac. It begins with static and bells, and a hand-drawn title card depicting something that looks like a radio. Nothing happens. Then you click, and the title card recedes into the background a little. You click again, and it recedes further. A piano melody joins the bells. You recognize that the key mechanic of this game is simply clicking and holding, while occasionally moving the mouse around to gently change perspective.

You keep holding down the mouse button. Text appears. The text tells a story about an artist in a town where everybody is obsessed with machines. This artist is an expert machinist, but she has a deeper ambition: “she dreamed about touching people’s hearts.” (The text of The Sensational December Machine is fable-like and nakedly sentimental, like a children’s Christmas story.) The artist spends a whole December on her latest gadget, and fills it with “words, sounds and pictures.”

When the artist finishes her machine, she takes it to the town square, where she’s met with utter incomprehension from a public that expects something other than what the artist set out to deliver. When the artist attempts an explanation, that the machine is simply for inspiring emotions, the public responds that “this was not something machines could do.” Hold the mouse button a little longer, and the words “or even should” are shunted into the sentence.

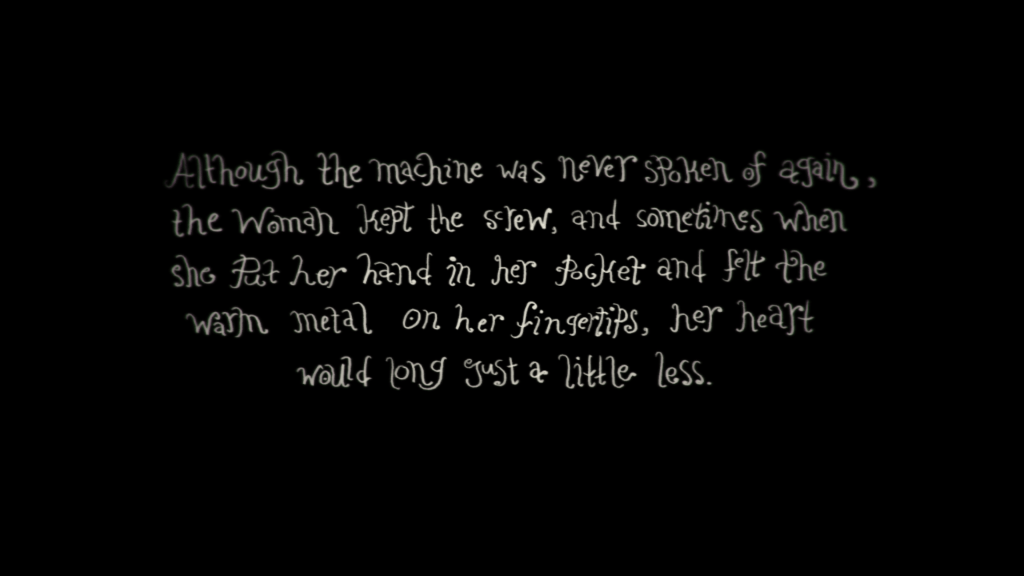

The artist sours on her own creation. Frustrated by its reception, she leaves it to rust in an alley. “Why make something no one wants?” The machine is forgotten within days. But every now and then, the artist reaches into her pocket to feel a screw that came loose from the machine as she left it in the alley. She recalls her creation and she feels a sense of fulfilment, regardless of everything else that’s happened in the story so far.

A hand-drawn Simogo logo appears, and you hit Esc to quit.

The Sensational December Machine is a five-minute experience that says more about its creators, and more directly, than anything else they’ve ever released save possibly for Lorelei and the Laser Eyes. The story dramatizes the creation and reception of The Sailor’s Dream, Simogo’s most ambitious but least gamelike game, which was their first release that didn’t match the critical and commercial success of its predecessors. Its mixed reviews from both critics and players tended to reiterate the same tedious points: the game is too short, provides too little agency, and isn’t a game. Reviewers consistently fell back on the old consumer journalism tendency to compartmentalize and rate the game’s elements separately (story: good; art: great; gameplay: ???), and to ask whether a game with such limited interactivity could possibly be worth the money. (I’ll defer to Noah Caldwell-Gervais on Kentucky Route Zero to refute this.)

As clapbacks to the haters go, The Sensational December Machine is remarkably graceful. Instead of obsessing over the community’s reaction to their creation, Simogo’s story echoes Kurt Vonnegut’s advice to grade school students on creativity: “Practice any art… not to get money and fame, but to experience becoming, to find out what’s inside you, to make your soul grow.” One could argue that you don’t make a game like The Sensational December Machine unless you’ve felt a certain amount of creatorly spite and resentment. Certainly, the game portrays the townspeople who wilfully misunderstand the machine as parodically myopic and shallow. And the fact that this story is defiantly un-interactive (a descriptor that frankly does not apply to The Sailor’s Dream) also suggests a certain amount of “I’ll show you.” But ultimately, the story emphasizes an important and altogether more empowering perspective: that art is not fundamentally a commodity, and that the relationship between an artist and the art itself is more crucial than the relationship between the artist and their audience. Some would call this attitude self-indulgent. Kurt Vonnegut would say: “you have made your soul grow.”

I’m tempted to leave it at that, but I can’t help feeling that the critical discourse being relitigated here is not over, even a decade later. Simogo’s early career was informed by the promise of smartphones: specifically, the promise that they would enable people who were otherwise uninterested in games to become interested in them. The success of Year Walk and DEVICE 6 suggested that there was an audience out there for well-made games that didn’t hew to the tedious genre trappings of AAA products (spacemen with guns and jumping children’s cartoons) and that renounced the gatekeeping of unintuitive controls. The failure of The Sailor’s Dream does not, in my view, contradict this. It simply speaks to the challenges of creating art in a milieu where art is generally received as a commercial product to be compared against other similar products for feature richness and value for money.

The historical moment when the smartphone seemed poised to transform games into a democratic, aesthetically heterogenous Big Tent without gatekeepers was over by late 2014–we explored this in the last part of this series. A decade later, the indie games space has evolved into almost this exact environment, albeit still one inhabited by dedicated enthusiasts and not the general public (and one in which smartphones remain a tertiary part). Still, even in this era of abundance and openness, you occasionally encounter the same critical attitude directed at The Sailor’s Dream ten years ago–the attitude reenacted by the townspeople in The Sensational December Machine.

When the (non-indie) studio Obsidian released their small-scale medieval RPG Pentiment in 2022, the reception was broadly positive. Nevertheless, some reviews emphasized that it is “not for everyone.” The game’s director Josh Sawyer offered the simplest response: what is? But even beyond that, asserting that Pentiment is specifically “not for everyone” is bizarre. It’s on Game Pass, and it’s short enough that you can finish it within your trial month. It runs on the laptop you use to answer your emails. Its RPG systems don’t involve any numbers at all, nor do they require any pre-existing familiarity with RPG mechanics. And its story fits the popular mould of historical fiction, which ought not to be any more alienating than science fiction or fantasy. I’m inclined to suspect it is less alienating. Each of these considerations would seem to make Pentiment more approachable than your average AAA game, not less. Yet they’re seemingly the very reasons why it was received as an outlier–a niche product. All of this in spite of the game’s deep interactivity and its very video gamey focus on moving a little guy around on a screen.

During Simogo’s first five years, one of the main ideas floating around in the games discourse was that devs needed to branch out from the most entrenched stories and mechanics if the entire medium was to become less niche. The reception of Pentiment demonstrates that even today, games that are demonstrably more accessible and approachable than standard AAA tentpoles are still sometimes regarded as less “universal” than those games.

This is the notion that Simogo gracefully declines to refute here. Good for them. And alas.

SPL-T (2015)

Simogo is maybe the only developer that could make a game that feels like something by Tale of Tales, and immediately follow it up with a game that feels like something by Zach Gage. If The Sensational December Machine was an epilogue to their trilogy of increasingly narrative-focused adventure games, then SPL-T serves as a prologue to a new era with a renewed interest in the elegant score chasing of Simogo’s early work.

Development on Sayonara Wild Hearts was well underway by the time of SPL-T’s release, so it may be a stretch to characterize it as a second response to the poor reception of The Sailor’s Dream. But it feels like it is. It feels like a deliberate shoving of the pendulum as far in the other direction as it’ll go–an exercise, perhaps, to see if the old arcade muscles are still in fighting trim. It took five weeks to make and it’s the most austere, narrative-free experience Simogo has ever produced. Narrative will reassert itself in their work almost immediately, but it’s still hard not to view SPL-T retrospectively as a statement of purpose for their next creative phase, during which nobody will ever accuse them of making something that is “not a game.”

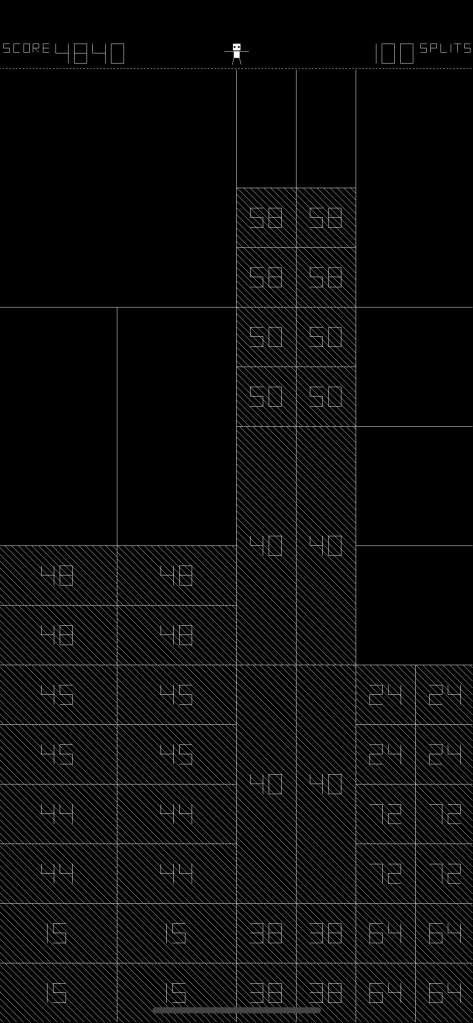

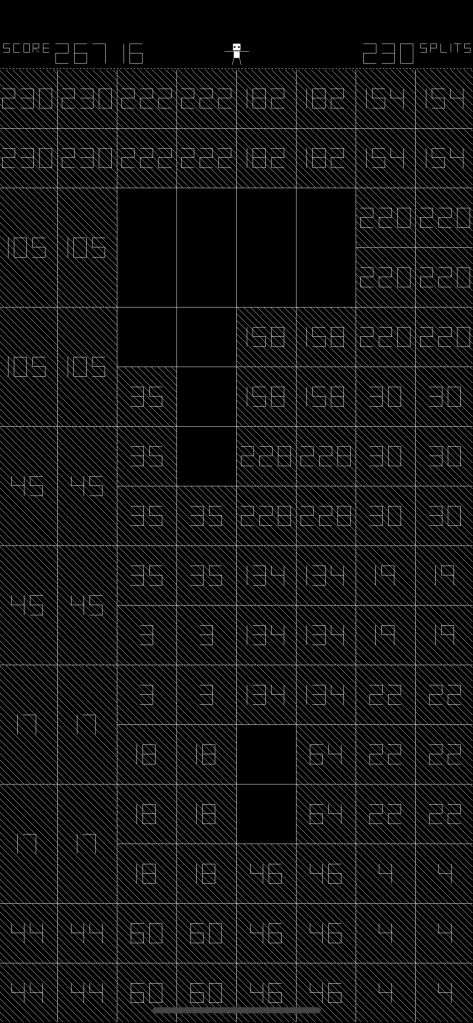

SPL-T’s basic mechanics are elementally simple: you tap the screen, and a horizontal line divides it in two. Then you tap one or the other of those two halves, and a vertical line divides that half once again. The entire game is a succession of alternating horizontal and vertical lines, always splitting a section of the playfield in two equal parts, until a part becomes indivisibly small. There’s a Cute Little Guy at the top of the screen doing semaphore at you to tell you whether it’s a horizontal or a vertical line coming up.

When a split creates a group of four or more equally-sized blocks, those blocks are frozen in an unsplittable state, regardless of their size. A number appears on the blocks: the current number of splits that you’ve made so far. With each new split you make, the numbers on your point blocks reduce by one, and when they reach zero the block disappears. Every point block above it on the screen drops down to fill the space and, in the game’s most immediately hooky mechanic, all of those dropping point blocks have their numbers cut in half. Stack your point blocks strategically, and you’ll have cascades of them dropping with each new split.

The first time you see a point block drop downwards, you might be surprised to learn that there’s a gravitational pull towards the bottom of the screen. Nothing before this has suggested that we’re looking at the playfield from the side. We could just have easily been seeing it from a bird’s eye view, drawing lines on a map. But the moment that rectangular blocks begin to fall vertically, SPL-T enters into a dialogue with Tetris: the most successful “casual” game of all time. It’ll be instructive to bounce these games off of each other.

The most fundamental difference between SPL-T and Tetris is the pace. There’s no time pressure in SPL-T, and progress occurs on your time–not the game’s. The meditative power of Tetris is that it locks you into the present moment, commanding your attention and focussing it on a single time-sensitive task. SPL-T doesn’t do this. Instead, it offers all the time you need to make your next decision, like a sudoku or a crossword puzzle. This is the key difference between SPL-T and its distant ancestor: Tetris is meditative; SPL-T is not meditative. SPL-T is chill. It declines to short-circuit your rationality the way that Tetris does, engaging your conscious mind rather than your instincts. Entering a flow state while playing SPL-T is not out of the question, but the flow state giveth and the flow state taketh away. If you become single-mindedly focussed on how things are working in your favourite little corner of your rectangle machine, you inevitably miss the big picture. You fail to think holistically. And you accidentally create a massive point block that ruins your whole goddamn game.

So, Tetris and SPL-T are only superficially similar. But they feel more similar than they are, because they’re both among the rare games that exist in a space of complete abstraction. Part of the reason Tetris is more universal than, say Dr. Mario is that the latter modestly incorporates narrative: you’re a doctor, and you’re fighting viruses–whereas, in Tetris, you’re you, and you’re playing a video game. Even in Candy Crush, while it’s unclear what you’re actually accomplishing by eliminating candies, they’re candies–whereas, SPL-T depicts only space on a screen, organized into increasingly chaotic divisions. The only representational images that appear in SPL-T are the semaphore guy and a little frog who appears on the help screen, both of whom take up minimal space on a screen that remains mostly dedicated to rectangles. This purposeful lack of iconography–of branding–lends an air of elegance to both SPL-T and Tetris. Like instrumental music or abstract expressionism, these games are about nothing but themselves.

There’s no randomness in SPL-T: every game starts the same way, and any given playthrough is perfectly replicable. Once you’ve spent a good bit of time with it, you may find yourself drifting towards familiar approaches, as if by a footpath of your own making. My default, unthinking approach is to arrange half the screen into point blocks yielding constant points, while the other half of the screen is a scrapheap of random shapes I only touch when I can’t find a good split on my main half. Playing this way, it only takes a few minutes for a blank screen to transform into a landscape of tiny, interconnected economies: resource extraction in the southwest leads to profit in the northeast. Given the lack of randomness in the game, there’s nothing preventing me from playing this way every single time–except for the lurking sense that there must be a better way.

Simogo marketed SPL-T with IKEA-like Swedish plainspokenness. “We know,” the game’s single, 34-second trailer states, “It doesn’t look like much. And this video is probably not going to sell you on it. But we promise that it’s really good. Like, really good.” The trailer explains nothing, and shows barely more than a few seconds of gameplay. But SPL-T, like DOOM, speaks for itself. Even without knowing the mechanics, or how deep the game becomes once you gain familiarity, you can see what SPL-T is from a couple seconds of gameplay footage: a return to basic principles, invoking the purity-by-necessity of not just Tetris but even earlier games like Pong and Asteroids, whose aesthetics it more closely resembles.

It might be enough that the trailer lets you hear the sound. The sound of SPL-T is its connection to Simogo’s legacy of tactile delights. Each time you place your finger on the screen and release, it’s like popping a little electronic kernel of popcorn. Horizontal splits and vertical splits are tuned a major second apart, giving the game a constant feel of unresolved tension, until a point block vanishes and a little melodic figure brings relief. The music itself, repurposed in uncompromisingly retro fashion from Kosmo Spin and Bumpy Road, taps against your eardrums like a blacksmith striking the world’s tiniest anvil. The sound and feel of the game are as thoroughly considered as any of the interactables on the islands of The Sailor’s Dream.

When Simogo released the game, it seemed a little slight to some of Simogo’s devoted players, accustomed as they were to the overflowing fictions of Year Walk and DEVICE 6. Surely, the makers of such impish games as these wouldn’t produce something… straightforward. The momentary presence of a frog on the final help screen even drew speculation that the game might be connected to Frog Fractions, another game whose fiction famously escapes its boundaries.

Unless something earth shattering remains undiscovered about SPL-T nearly a decade later, this turned out not to be true. The game does contain some entertaining secrets, such as a hidden ball-balancing game that reveals itself when you press and hold the game’s title, and the ability to change the colour scheme by shaking the phone or turning it upside down (good luck actually playing that way, though). Most notably, if you wait long enough on each of the help screens, you’re shown a series of messages from an unknown sender: an almost-story told as a one-sided conversation between a mysterious consciousness and an unseen second party. It’s suggestive, but it doesn’t motion towards any further secrets or any compelling interpretations.

It’s entirely possible that twenty years from now, somebody will unearth a massive secret from within SPL-T that places it alongside DEVICE 6 and Lorelei in Simogo’s pantheon of uncanny metafictions. I doubt this: the fact that SPL-T’s simplicity was so hard for some players to accept is simply a reflection of how completely Simogo had come to be identified with the complex narratives of their last three major releases, and how little they were known as the creators of Bumpy Road. In 2019, the idea that they’d want to create something as uncomplicatedly gamey as this would suddenly become much easier to accept.

A final note: although SPL-T is the Simogo game that least needs a sequel, it is their only game that has one. Nestled within the folds of Lorelei and the Laser Eyes, you can discover SPL-T 2, a feature bloated, perhaps intentionally worse version of SPL-T that serves Lorelei’s commentary on art and commerce, similarly to the bonus content in The Stanley Parable: Ultra Deluxe. Simogo claims it may inspire “the strange sensation of lessening your opinion on the predecessor.” Inferior as it is, I have not found this to be the case.

Sayonara Wild Hearts (2019)

There are only a handful of moments in music history when a cult artist made a record so pure and undeniable that they broke through to a mainstream audience without significantly changing their approach. The archetypal example is The Dark Side of the Moon, an album whose self-seriousness makes it an odd fit to even mention in the context of Sayonara Wild Hearts. Better analogues come from the pop songwriter world: Heartthrob by Tegan and Sara; So by Peter Gabriel; Hounds of Love by Kate Bush.

Sayonara Wild Hearts is a work like this: a warm embrace, human and relatable, that still maintains the particular mannerisms and idiosyncrasies that made its creators interesting in the first place. It is Poptimism: The Video Game, and not just because of its musical reference points. Its fundamental attitude is a belief in people, and a sense that there are universal experiences worth expressing through the closest thing possible to universal means. Simogo has always worked in a big tent, but Sayonara skips wildly and joyfully along the surface of mass culture to create something more inviting and enveloping than anything in their catalogue so far.

This change of attitude is a subtle thing. Simogo’s previous games were all obsessively honed towards accessibility, with an eye towards attracting players who didn’t normally play games. But perhaps this gave the impression of a certain aloofness towards the medium in which they were working–a deliberate distance from the type of games made for people who do normally play games. Envisioning new audiences often means alienating the existing one to some degree. The paradox of Year Walk, DEVICE 6 and The Sailor’s Dream is that they are simultaneously more accessible to inexperienced players than most hit games–and they are highly ambitious, far-reaching and artful works that ultimately seem to be courting a cult audience. Simogo is hard to pin down. Calling them pretentious would be outright rude, given their commitment to accessibility and their philosophy that games should be for everyone. But trying to paint them as video game populists is somewhat challenging because of the esoteric and literary tenor of their best-known works.

Sayonara Wild Hearts kicks dirt in the face of this entire, tortured train of thought. It does so by being, as Simogo themselves put it: “unashamed of being a video game.” No more languid exploration. No more long chunks of text. No more interactive music boxes. Motorcycles. Lasers. Fail states. Accordingly, on its release day, Sayonara Wild Hearts was released not only for mobile devices, but also for Nintendo Switch and PlayStation 4. Knowing all too well that there’s a gendered component to making a game that’s “unashamed of being a video game,” Simogo gave their laser motorcycle game a queer female protagonist, built it around an effervescent pop music score, and made it, just unbelievably purple.

On Sayonara Wild Hearts, Simogo had their cake and ate it too. They once again refused to cater solely to the narrow sliver of the public that so many developers rely on–and they also made a fucking Video Game.

Sayonara’s universality begins with the story: a hero’s journey narrative, where a reluctant protagonist completes a quest through what ultimately turns out to be an interior landscape, and emerges transformed. The idea of the “monomyth” has become a tedious self-fulfilling prophecy ever since Hollywood screenwriters started reading Joseph Campbell. But if you’re aiming for universality, market research suggests you could do worse. Though its protagonist is a young adult, Sayonara fits the mould of classic coming-of-age fantasies like The Wizard of Oz, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and Labyrinth, where the main character’s journey through a new reality changes their outlook on the mundane world they eventually return to:

“And you think of all of the things you’ve seen

And you wish that you could live in between

And you’re back again, only different than before

After the sky.”

Sayonara Wild Hearts takes place on either side of a beanstalk: a threshold between the mundane and the fantastical. The very first cutscene, which plays as soon as you boot up the game, keeps us on the mundane side of the beanstalk: a heartbroken young woman skates forlornly away from a falafel shop. Shortly after, another cutscene at the start of the first level situates us within a fantastical tarot-inspired cosmology involving the fracturing of a once-harmonious universe. In two cutscenes, we understand the twin facets of this story: the personal and the cosmic.

So where is the beanstalk itself? What sits between these two scenes that introduce us to our two realities? The title screen. In a sense, every game’s title screen serves as a threshold between the mundane and the fantastical: it is the passageway that leads from the material world you were living in before you switched on the console into whatever constructed reality waits therein. But Simogo’s title screens tend to make this even more explicit. Sayonara‘s is effectively a synthpop rewrite of the opening of The Sailor’s Dream, which depicts its protagonist crossing the threshold between waking and sleep. Like Sailor, Sayonara begins with a snippet of narration (by Queen Latifah, no less) that makes the boundary explicit: “So our saga begins tonight, yet aeons ago, just here, yet lightyears away.” A couple of logos later, we’re tumbled into a violet universe of strobe lights and sidechaining. The title itself beats at us like a heart, in rhythm with the first of Sayonara’s eight Jonathan Eng songs, all performed by Swedish pop singer Linnea Olsson. “Everything is strange,” Olsson sings, “the end of love doesn’t happen this way.” This is the denial that must exist at the start of any Campbell-approved hero’s journey. It’s up to you whether you sit in that denial for the song’s full 90-second duration, or leave the First Threshold in the dust the second your eyes alight on the “Start Game” option.

It’s remarkable how quickly after this ascension into the sublime that we find ourselves pretty much just playing Subway Surfers. In 2019, Subway Surfers hadn’t yet become a primary component of “sludge content,” a multi-screen experience in which no single element is worth anything. But even then, it felt shocking to see Subway Surfers embedded as such a clear reference point in a game by such an ambitious developer. Some of the same habitual Simogo players who vainly sought a grandiose metanarrative in SPL-T might also have been flummoxed by Sayonara Wild Hearts, which contains precious little text, not the faintest hint of metafiction, and a couple of levels that are almost literally just Subway Surfers.

But if the brief “intermission” encompassing The Sensational December Machine and SPL-T indicates anything at all, it’s that The Sailor’s Dream marked a turning point. It’s quite possible that Sailor was always intended as the final instalment of a narrative-focussed trilogy (Simogo claims as much in retrospect). But the game’s relative failure must have also helped to push them in another direction–you cannot go on making Sensational December Machines forever. With The Sailor’s Dream safely relegated away in “make your soul grow” territory, it makes much more sense that their next project would uncannily resemble the casual mobile games of several years prior–the environment in which Simogo started their career. Thus, Sayonara materialized as a belated companion to Kosmo Spin, Bumpy Road, and Beat Sneak Bandit.

Of the three, it resembles Bumpy Road the most. Superficially, they share a genre: they’re both autorunners–as is Subway Surfers. But the last time Simogo played in this sandbox, Subway Surfers wasn’t even available as a format to riff on. Bumpy Road predates it by nearly a year–and even predates Subway’s predecessor Temple Run by a couple of months. The 3D autorunner hadn’t been codified yet, leaving Simogo to subvert the genre in two dimensions. Sayonara adds the third, but it doesn’t subvert its predecessors as fundamentally as Bumpy Road did. Aesthetics aside, it is mostly just a sequence of well-timed dodges. Its main difference comes in the fact that it is not an endless runner: it is divided into discrete, finite levels that each offer something new.

The framing of these levels takes after Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World: our protagonist, having Crossed The First Threshold, must now defeat mystical representations of all her exes. Every character is inspired by one of the Major Arcana: the player character is the Fool, a figure analogous with Joseph Campbell’s archetypal hero. Each ex and their posse is identified with a particular tarot card: the Devil (a troupe of dancers), the Moon (a bunch of howling wolf people), the Lovers (a person that’s actually two people), the Hermit (a gamer, hilariously), and Death (the protagonist’s canonical Big Ex, “Little Death”: a French euphemism).

Each ex is the focus of a series of levels that offer a constant stream of stimulation. The fixed perspective of Subway Surfers is replaced by a dynamic, constantly shifting camera whose unpredictability adds a little extra challenge, and also makes you genuinely feel like you’re in a music video. The levels rip through the history of pop culture, pillaging images and sounds from disparate quarters and smashing them together so confidently that nothing ever feels out of place. Simogo’s games have often played like interactive “mood boards,” but never more than here: we’ve got Carly Rae Jepson, the occult, cosplay, Mario Kart, bisexual lighting, Final Fantasy VII, and the 75% of Tumblr not already accounted for by the rest of this list. Sayonara’s flood of references, images and themes only coheres because its central mechanic is so simple and consistent. Just keep dodging and watch the pretty colours zip by, and in the end you’ll be surprised by how much of the game’s content got through to you somehow.

Once the Fool has chased down every one of her exes on motorbike, hoverboard, and vintage car, KO’ed them to the rousing approval of Queen Latifah, and released the monster lurking within Little Death, we learn an additional layer of mystical truth: each of these past lovers has been, in a sense, the Fool herself. The last level finds the Fool giving a loving, platonic smooch to each of the game’s characters in sequence–all of them having taken on elements of the Fool’s own character model. Sayonara predates the dominant cultural phenomenon of the moment during which I’m writing this: the Eras Tour. And for all its poptimism, Sayonara’s sensibility is a shade more indie than Taylor Swift. But somehow, it presages the key message that Taffy Brodesser-Akner took from Swift’s gargantuan global spectacle: that a key element of maturity is extending grace to your various past selves–however troubled, however embarrassing.

In that sense, Sayonara Wild Hearts plays like an autobiography. There’s nothing particularly embarrassing in Simogo’s corpus, but it is a body of work characterized by a couple of clean breaks with the past. Sayonara brings all of Simogo’s past selves together in blissful coexistence. Even as it refers back to the sensibility of their earliest work, Sayonara continues to be in dialogue with The Sailor’s Dream, just like the two smaller games that preceded it. It synthesizes the arcade gameplay of Simogo’s first three games with the expressive presentation they honed on Sailor. Sayonara is fast where Sailor is slow, and Sayonara offers ecstasy where Sailor offers reflection. But the priority Sayonara places on sheer audiovisual splendor is characteristic of a post-Sailor Simogo. This game simply doesn’t exist in a world where Simogo didn’t previously create their narrative works.

It also doesn’t exist in a universe where Simogo hadn’t built a relationship with Jonathan Eng–a relationship that fully flowered on Sailor, and which arguably reaches its apex here. Eng’s Sayonara songs take after the grand Swedish tradition of ABBA and Robyn: heartbreak anthems aiming for maximum catharsis. His original sketches for these songs are in a different sonic universe from where the game ended up. It’s easier to imagine some of them as Bon Iver-adjacent anthems of lo-fi anguish in the woods than as the synthpop bangers they actually became. But while Eng was on his own making music for Sailor, here he’s collaborating with Simogo’s longtime composer Daniel Olsen.

Olsen hasn’t come up yet in this retrospective, mainly because Eng is a more novel figure: it’s common enough for a game studio to have a go-to composer, but not a go-to songwriter. But Olsen’s work on Sayonara is more integral than ever. He transforms Eng’s introspective demos into CHVRCHES songs, then does the same with piano music by Debussy. Elsewhere, the instrumental score drifts through Daft Punk and Kaminsky before ultimately settling back into the sweet spot of Carly Rae Jepson’s Emotion. Released during the first year of Sayonara‘s development, Emotion is manifestly an inspiration. It’s a record of loud, glossy exteriors hiding a broken, Sinatra-like inwardness. Emotion’s best cut, “Your Type,” feels like a clear model for Sayonara’s title track, and Sayonara’s pop tunes share a sense of purpose with Emotion: they both reach for catharsis by fusing misery with ecstasy.

This aesthetic evaporates just as the credits start to roll. Sayonara’s final song, “A Place I Don’t Know,” was a country song Eng hadn’t originally intended for the game. Its final form is semi-acoustic dream pop, with an almost whispered vocal performance by Linnea Olsson that suggests a new maturity that’s absent from the callow narrator of previous songs like “Mine” and “Inside.” The lyric is, on its face, an odd fit for the end of a story about self-love. It is clearly a love song directed at a partner. But the relationship it describes seems different from the previous ones hinted at throughout the game:

“I was used to my safety and peace

I mistook all this tedium for being at ease

But then you came along and said it’s time to let go

And you took me to a place I don’t know.”

In its final moments, Sayonara Wild Hearts suggests that the self-love it celebrates in its final level isn’t only an end in itself, although it certainly could be. It also provides the courage that’s a prerequisite for real commitment–real love. For the second time, Jonathan Eng delivers the emotional kicker at the end of the story.

Is it really possible that one of the five or six most beautiful love songs ever written is hidden in the end credits of a racing game?

Yes.

I hadn’t originally intended for this section to end here. My plan was to cover the two small post-Sailor games quickly, and then dedicate the bulk of this third part to the third major phase of Simogo’s career, constituting Sayonara Wild Hearts and Lorelei and the Laser Eyes. But this is quite long enough for one post, even without trying to shoehorn in the densest text in Simogo’s whole output. The next and final instalment will be entirely dedicated to Lorelei. It will be a standalone post, but it will also serve as “part 3.5” of this series, the second of Simogo’s two secret sequels.

I’m satisfied that it turned out this way in the end, because it strikes me now that the three games we’ve covered here are part of a single continuous motion. Together, they constitute a reaction to the end of Simogo’s prior phase: the critical dismissal of The Sailor’s Dream, the exhaustion of a particular creative direction, and the end of the smartphone as a new and promising expressive technology. Lorelei doesn’t strike me as part of this same continuous motion. It’s of a piece with Sayonara in a way, looking backwards for inspiration in previous successes. But after Sayonara, it feels like Simogo has tied up their various preoccupying loose ends. Lorelei, for all its open nostalgia, is something new.