Every body of work belongs somewhere on a spectrum between order and ungainliness: between Nine Inch Nails and Aphex Twin, perhaps. There is an appeal in the Aphex Twin kind of catalogue, scattered among different monikers and doled out in irregular quantities. The treasure hunter in me appreciates the challenge. But my heart belongs to the artists who keep their garden well weeded, who impose their own sense of order onto their work. It isn’t mere vanity that might compel an artist to act in this way. To actively corral and demarcate a list of works is an invitation from artist to audience, to look at all of this material as a cohesive whole: to see each individual part in conversation with all the others.

Over the last 15 years, the indie developer Simogo has built up one of the most internally coherent back catalogues in games. This coherency lends depth and meaning to each game in itself, especially their latest: Lorelei and the Laser Eyes. Lorelei contains explicit references to Simogo’s entire corpus, from their earliest mobile trifles to their most ambitious adventure games. It expands on themes and approaches that have defined Simogo’s work since the start of their career.

The release of Lorelei strikes me as an opportunity to look back at Simogo’s complete works, to attempt to trace the consistent voice that runs through their catalogue. As in the past, I don’t have a specific thesis or grand unified theory of Simogo I’m working towards here. I’m just going to play all of their games, and go through some of the ephemera associated with each. I’ll comment on what strikes me most, and how each part seems to inform the whole.

Here’s the “shape” of Simogo’s catalogue as I see it, laid out in parts and subparts:

A trilogy of casual mobile games:

- Kosmo Spin

- Bumpy Road

- Beat Sneak Bandit

- A playable demo called Rollovski, for an unreleased Nintendo 3DS game in the same universe as Beat Sneak Bandit

A second trilogy of metafiction-inclined adventure games for mobile:

- Year Walk

- The Year Walk Companion, a separate app expanding on the folklore that inspired the game and containing important secrets (the Companion was folded into subsequent ports of Year Walk)

- Year Walk Bedtime Stories for Awful Children, a set of short stories written for the release of the Wii U port

- DEVICE 6

- The Sailor’s Dream

- A fiction podcast called The Lighthouse Painting

An “intermission featurette” containing two small and contrasting works:

- The Sensational December Machine

- SPL-T

Two comparatively large games that appear to follow up on approaches from their first and second trilogies, respectively:

- Sayonara Wild Hearts

- Lorelei and the Laser Eyes

That’s a lot of games, so I’m splitting this into a three-part series. This first part will deal with the early casual games. The second will cover Year Walk, DEVICE 6 and The Sailor’s Dream, with all their associated ephemera. And the final part will touch on the two small titles in the “intermission featurette,” then dive into Simogo’s two most recent games. (Edit: As it turns out, Lorelei required a post all to itself. So, this is in fact a four-part series. The schematic still applies.)

Me and Simogo, we go back a long way. Playing DEVICE 6 in 2013 was one of a handful of experiences that encouraged me to get back into games after a long absence. The point of this retrospective isn’t really to assess the quality of what Simogo has made, but the fact that I’m doing this at all should demonstrate my personal attachment to their work. I’ve played everything from Year Walk through Sayonara Wild Hearts at least three times each, and I’m the particular kind of sicko who considers The Sailor’s Dream to be their secret masterpiece. I’ve thought about these games a lot.

On the other hand, Lorelei and the Laser Eyes is as new to me as everybody else, and I hadn’t played Kosmo Spin, Bumpy Road or Beat Sneak Bandit before I started working on this series. So there will be an element of discovery here. The more I play these unfamiliar games, the stronger the sense I get that Simogo’s current creative phase is explicitly in conversation with their own past. Sayonara Wild Hearts strikes me as a spiritual sequel to their initial trilogy of casual mobile games. In the same way, Lorelei seems to follow up the metafiction trilogy that began with Year Walk. Simogo redesigned their website for the release of Lorelei, including reams of documentation and present-day reflection on their previous games. Their catalogue has never been tidier, and its coherence has never been more relevant to their current work.

A final note before we begin: I wrote earlier that I have no particular thesis I’m working towards. I do however see a correlation between Simogo’s work at any given time and the prevailing attitude towards smartphones. As we proceed, we’ll witness the rise of the smartphone as a casual entertainment device, its embrace by indie developers as an accessible platform for interactive storytelling, and the gradually declining optimism about its possibilities over the last ten years. Another fact that marks Lorelei and the Laser Eyes as a turning point in Simogo’s work is that it’s their first game not to be released on mobile, which has been their natural habitat for most of their career.

We’ll get there, but first: back to a more innocent time.

(This series will ultimately contain full spoilers for every Simogo game, but that isn’t particularly relevant to the early games covered in this part.)

Kosmo Spin (2010)

Kosmo Spin was the first game that Simon Flesser and Magnus “Gordon” Gardebäck made as Simogo, but not the first game that they worked on together. Their most relevant pre-Simogo work, ilomilo, falls outside the scope of this retrospective–though it lives on through a minigame in Lorelei and a Billie Eilish song.

It’s easier to appreciate Kosmo Spin when you consider it as a snapshot from 2010: that’s three years after the release of the first iPhone, two years after the launch of the App Store (which had about 150,000 apps in total at the time, compared with today’s two million), and one year after the medium-defining success of Angry Birds. Kosmo Spin was released anywhere from one to two years after you first saw that app that made it look like you were drinking a beer–the Train Pulling into a Station of our time. The iPhone was a blank canvas, a new technology so void of preconceptions about what it could do that even the dumbest applications of its motion sensors and touchscreen seemed novel.

The touchscreen in particular felt like it would initiate a new era, where you would no longer need to learn a piece of software, it would simply behave how you expected it to. The intuitive physicality of the touchscreen, and the fact that everybody suddenly had one in their pocket, enabled a generation of indie game studios. Simogo is a child of this moment, and Kosmo Spin is a modest relic of its time.

The fundamental feature of Kosmo Spin is that it uses only one input from the player: moving your thumb in a circle on the touchscreen. Doing so spins the planet at the centre of the screen while your character, Nod, remains on top of it. The main threat is a flying saucer floating around above the planet that can use a tractor beam to abduct Nod, ending the game immediately, or fire various balls with different movement patterns at the planet, briefly stunning Nod and preventing you from spinning the planet for a second or two.

Kosmo Spin’s single input allows you to accomplish a small handful of tasks. Most importantly, you can collect the “breakfast thingys” that spawn along the edge of the planet. This is the thrust of the game: an alien has come to this planet to steal their breakfast, and Nod is breakfast’s saviour. He can also head the balls the flying saucer shoots, which may in turn collide with other balls or with the flying saucer. That’s a more or less complete summary of the mechanics of Kosmo Spin. It is elementally simple: Pong, but circular. It’s an idea so obvious that it seems bizarre that it didn’t happen until 2010. All it took was the widespread availability of touchscreens and a wave of enthusiasm for new tactile experiences.

In its day, Kosmo Spin was promoted for its originality–“a one of a kind circular arcade game.” That originality is less obvious from today’s vantage point, when the Lumiere-like novelty of the touchscreen is a distant memory. The main reason to play Kosmo Spin today is to do what I’m doing: to add context for Simogo’s later work.

There are a couple threads that begin here and run throughout Simogo’s catalogue. The simplicity of the controls is one. Simogo’s games have become enormously more complex, but their belief in simplifying game controls persists to this day. In fact, it persists to such an extent that some critics are finding Lorelei’s two-input system too simplistic for the game’s purpose.

The other thread worth noting is everything that falls under the heading of “presentation.” Kosmo Spin is visibly a game made by two people in a few months, but it embraces those limitations and spins them into an aesthetic. Everything about Kosmo Spin is low-stakes and homespun: the cut paper collage look of the menus, the ukulele-led score, and so on. Even the release trailer features fabric puppets on a cardboard set. As minor as it is, Kosmo Spin is as holistically designed an object as DEVICE 6 or Sayonara Wild Hearts.

There is a sort of story mode in Kosmo Spin, where you take quests from a handful of deliberately one-dimensional NPCs whose personalities boil down to encouraging, crotchety, stoned, manic, murderous, arithmomaniacal, hesitant and French. (There’s also a little Einstein lookalike who offers a “Space & Breakfast Fact” if you scroll past the last screen of levels: whimsical little remarks that fall short of actually being jokes.) I have not finished this campaign. I’ve attempted all 60 of its quests and completed 39. For all I know, beating the game could reveal that Nod has been the player character in Year Walk all along. I’ll never see it for myself, because even I have limits. Kosmo Spin is mainly compelling in the same way as the first David Bowie album: a suggestion of interesting things ahead.

It’s also a nostalgic portal back to a time when browsing the App Store was kind of fun. I can’t remember exactly when that ceased to be the case, but it was probably sometime after 2011.

Bumpy Road (2011)

It didn’t take long for the smartphone’s infinite possibility space to present a few obvious paths of least resistance. The success of Canabalt in 2009 opened one of them: the auto-runner, and its subcategory the endless runner. Simogo released Bumpy Road three months before the definitive side-scrolling endless runner, Jetpack Joyride, and only two months before the wellspring of 3D endless runners: Temple Run.

In retrospect, the ubiquity of this genre might make you yawn or gag, or despair at the swiftness with which predictable patterns exerted themselves in the open frontier of smartphone entertainment. But that’s what a genre is: a path through the possibility space that’s recognizable enough to be travelled again and again, but broad enough to suggest different ways of travelling down the recognizable path.

Bumpy Road itself is an enactment of this metaphor: its infinite scroll recalls the predictable elements of its genre, but the freedom of movement the player enjoys within that scroll (including backwards movement, a rarity) indicates just how much space for variation there is along the reliable genre path.

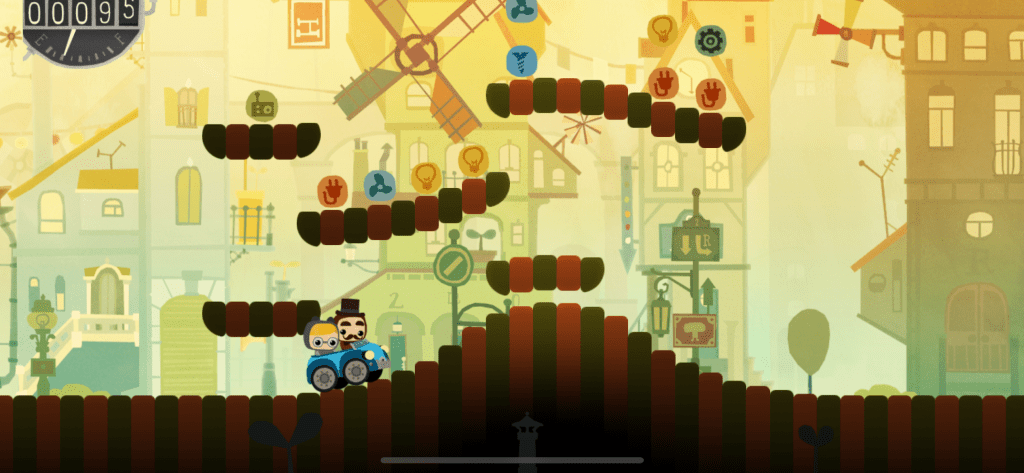

The elderly couple that acts as Bumpy Road’s protagonists, Auntie Cat and Uncle Hat, are not “player characters” as such. You choose which one of them is behind the wheel of their vintage car by selecting from the two available game modes. But once selected, they go on their own, leaving you to guide their motion by changing the shape of the road on which they travel. You do so by sliding your finger along the road itself, stretching it upwards and creating slopes for the car to accelerate down or bumps to stop it from careening into a game-ending hole.

The game’s frisson comes from the counterintuitive feeling of controlling something other than the moving object on the screen. The controls are simple to understand in concept, but perhaps intentionally awkward–a little like Katamari Damacy, or the future mobile sensation Flappy Bird. The game’s true endless mode, “Evergreen Ride,” puts the cautious Uncle Hat in the driver’s seat and challenges you to collect as many car-powering “gizmos” as you can while not falling into any holes. The more reckless Auntie Cat’s game mode, “Sunday Trip,” has a finish line and no holes to fall into, and challenges you to complete an obstacle course as quickly as possible.

A run in either game mode consists of a shuffling of discrete level segments in random order. As you gain familiarity with the game, you start recognizing these level segments as they begin. You remember to some degree what you’ll soon have to avoid and how you’ll need to position yourself to collect the more inconveniently placed gizmos. Bumpy Road sits somewhere between the memory-reliant classic Mario platformers and procedural roguelikes, which rely instead on an overall familiarity with the game’s whole realm of possibilities.

Once again, the game’s aesthetic is half the reason to play it. The homespun feel of Kosmo Spin is gone, replaced by a Triplets of Belleville-inspired French animation look. The ukulele is still here, but a top layer of melodica gives the music an extra touch of pâtisserie sophistication. There’s more of a story here than in Kosmo Spin as well: a love story presented in photographs you can collect in the “Evergreen Ride” mode. I will probably never see the end of this story, or even the bulk of it, in my own save file. The game is so parsimonious with its one meaningful collectible that you have to be either really good or extremely perseverent to see all 40 photographs. I am neither.

I simply cannot get a handle on Bumpy Road. In spite of its basic controls and detailed tutorial, the feel of it eludes me. Part of this may be because I’m playing it on the 6.1-inch screen of my iPhone 14 instead of the 3.5-inch iPhone 4 screen it was designed for. I always feel like I have to reach a little too far. It’s a step forward from Kosmo Spin in many ways, but it still strikes me as mainly a thing of interest for Simogo archeologists. If Kosmo Spin reflects the earliest days of freeform innovation with touchscreens, Bumpy Road represents Simogo’s response to the emergence of a predominant genre in mobile games.

Notably, it is the first of two auto-runners by Simogo. The other, 2019’s Sayonara Wild Hearts, is clearly the more ambitious game. But I don’t think it’s ridiculous to suggest that Bumpy Road is the more experimental game on a basic, mechanical level. In 2012, Subway Surfers picked up where Temple Run left off, and established a template that Sayonara Wild Hearts doesn’t stray too far from. Bumpy Road, on the other hand, doesn’t play anything like the other auto-runners of its era. It subverts the still-emerging expectations of its genre. Very soon, this will become one of Simogo’s favourite hobbies.

Beat Sneak Bandit (2012)

Simogo’s career started with riffs on Pong and Canabalt. The fact that Beat Sneak Bandit doesn’t immediately recall another specific game makes it a turning point. Similarly to Bumpy Road, it does make reference to well-known video game tropes. But this time, it subverts the tendencies of two genres, simply by smashing them together: stealth games, and rhythm games.

I suspect it’s also the only game where it would be possible to write a walkthrough entirely in musical notation:

This is a valid solution for chapter one, level four of Beat Sneak Bandit. It isn’t the most optimal solution, but if you tap on the quarter notes and wait during the rests, you’ll reach the goal and clear the level. You don’t even have to look at the screen.

The title character of Beat Sneak Bandit has been tasked with recovering the world’s stolen clock faces from the detestable Duke Clockface. Again, the game’s control scheme consists of a single input, the simplest one yet: tapping the screen to the beat of the game’s music. On each beat of a level there are only two things you can do: tap or wait. Tapping will move the title character forward if there’s nothing in his way, turn him around on the spot if he’s facing a wall, and move him up a staircase if he’s standing in front of one. Waiting will do none of these, though several passive effects may happen regardless, like falling through an open trapdoor, travelling through a teleporter, or getting busted by a guard and failing the level.

The entirety of Beat Sneak Bandit takes place on a temporal grid, like Dance Dance Revolution or Guitar Hero. But in those games, the grid is explicitly shown on screen with clear instructions about what to do on every grid line that passes by. The trick is simply to keep up. In Beat Sneak Bandit, the grid is hidden. The trick is deciding what to do on each beat: to tap, or not to tap? Nothing is random in Beat Sneak Bandit. Every level runs on a predictable loop, and the Bandit starts at the same place each time. So, while there are a number of possible solutions to each level, any given solution is guaranteed to work every time. That is what causes the extraordinary phenomenon that Beat Sneak Bandit gameplay can be transcribed like a bass drum part, into quarter notes and rests.

(Having investigated, I see that people have attempted to notate gameplay in this way before, for instance with Braid. But in that case, it took some significant alterations to the standard way of writing music. Braid’s gameplay isn’t tied to the audible grid lines of a steady beat. So, Beat Sneak Bandit remains the only game I’m aware of that’s transcribable in this way.)

On its face, it seems like a perverse decision to make a casual game you can’t play with the sound off. But Beat Sneak Bandit is more comfortable asking for your attention than its predecessors. Aside from Kosmo Spin’s quest mode, Beat Sneak Bandit is the first Simogo game with a proper campaign. It consists of distinct levels leading to a final boss and end credits. It’s the first time Simogo has invited the player to “beat the game.” But as with Sayonara Wild Hearts years later, you set the terms of your own engagement. Its levels are usually easy to beat if your objective is just to reach the goal and move on to the next level. But they can be quite challenging if you want to get all of the collectables. It’s genuinely more fun if you try to completely solve a puzzle, but if you see a shortcut and want to take it, the game neither stops nor judges you for it. Also like Sayonara, Bandit has a very generous level skip option that kicks in if you fail a few times in a row. It occasionally starts to feel condescending, but it’s a solution for a possible problem that arises here for the first time in Simogo’s career.

In Kosmo Spin, all 60 quests are available from the start. You don’t have to progress from one to the next to unlock further ones. Bumpy Road doesn’t have “levels” at all, instead offering two different kinds of score chasing. Beat Sneak Bandit is the first Simogo game that forces the player through a linear course of levels. So, it’s the first time it might be possible to get stuck. The level skip option ensures that the linear structure of the game maintains its integrity while also ensuring that the whole game is available to all players, just like it was in Kosmo Spin.

The one occasion when the game offers no grace is the extremely difficult final boss fight which comes in eight phases and sends you right back to the start if you make a mistake. But at that point the game is nearly over, and the only thing that’s locked behind the boss is a bonus stage of 12 variations on previous levels. Arguably, the bigger loss for being unable to finish the boss fight is not getting to hear the music over the end credits, which features songwriter Jonathan Eng on guitar. Eng previously worked with Simogo on cloying promo songs for Kosmo Spin and Bumpy Road but this is his first appearance in a proper game, and the start of the relationship that will make The Sailor’s Dream and Sayonara Wild Hearts possible.

More than either of the first two games, Beat Sneak Bandit feels like the origin point for a lot of elements that are present in Simogo’s most successful phase. The simple fact that it’s a bespoke set of challenges with a hard out rather than an arcade-like score chase accounts for some of this. But also, the first three games all have their own distinct visual aesthetic: arts and crafts in Kosmo Spin, French animation in Bumpy Road, and now Saul Bass posters and mid-century cartoons in Beat Sneak Bandit. Of those three aesthetics, this is the only one Simogo will revisit, in the even more Bass-inspired DEVICE 6.

Shortly after the release of Beat Sneak Bandit came a fork in the road. To one side, a prototype for a lore-rich game unlike anything Simogo had made so far. To the other, an invitation from no less than Nintendo. In 2012, their 3DS handheld didn’t have anything close to the reach of the iPhone, but it offered a unique set of possibilities. Simogo’s response to Nintendo’s invitation was a prototype called Rollovski, with the same art style as Beat Sneak Bandit and in the same fictional universe. But the gameplay feels much more like Bumpy Road, built around moving the environment rather than the character.

In the wake of Lorelei and the Laser Eyes being available on Switch but not on mobile, the Rollovski prototype feels like a harbinger of things to come. There’s an alternate universe where Rollovski made it past the prototype stage and became a massive hit. Maybe in that universe, Simogo continued making work in the same vein as their first three games. I’m sure it’s delightful there. But we live in a more haunted world than that.