Ken Russell clearly revered the composer Gustav Mahler. The eccentric filmmaker stated in his autobiography: “Only clichés can describe what nobody has ever been able to portray: a vision of God. Mahler got so near it.”

The characteristic that sets Russell’s Mahler apart from other music biopics is how doggedly it focusses on Mahler’s music itself, rather than simply telling the story of the composer’s life. Russell almost seems to be analyzing the music through images, at times. This is difficult terrain for a filmmaker to tread upon. I’m going to explain why, and it might get technical. Stay with me:

Film is a series of photographic images. At its most basic, it is a document of objects that were actually present in front of the camera, and therefore exist in space. It is a medium for concrete images. If that’s true, then music is the anti-film. Abstract by definition, it may evoke moods or trigger images, but these are, at best, subjective.

What I mean is this: If I showed 50 people a picture of a grey cat and asked them what the image was of, they’d probably all give me the same simple response: “It’s a picture of a grey cat.” But if I played you and your 49 friends a melody and asked what it makes them think of, I might just as likely get “marble columns,” “hibernating bear,” or “a craving for pancakes” as “grey cat.” The smartest of you would probably say “nothing,” or “that’s a stupid question,” because there’s something fundamental about music that you understand: there can be no specific meaning attached to a melody, or a chord sequence, taken in isolation.

That’s not to say that music can’t take on meaning, if it is effectively paired with something more concrete, like an image, or a narrative, or words. Think of ballets, operas, film scores and (obviously) songs. Music is malleable. It has no meaning of its own, so you can make it mean whatever you want.

Here’s the flip side of that idea: music, being abstract, steadfastly resists translation into any other medium. You could rework a story as a film. A scene from a novel could form the basis of a painting. You could even reverse those processes, with a modicum of creative license. But we’re still waiting for the day when we can sit through the credits of a film and see the words “adapted from Joseph Haydn’s String Quartet Op. 76, No. 2.”

(I should note here that this idea of music not representing anything specific is contentious. I have at least two former music teachers who would shudder to read this. But, among those in my corner is Igor Stravinsky, who argues this perspective in his Poetics of Music, and also in a famous essay accompanying his 1923 Octet. So, I feel vindicated. Also, this guy.)

Here’s what this all adds up to: music communicates to its audience on a different, more ephemeral level than any other medium. (You could argue for abstract painting or sculpture, I suppose, but I’ll leave that for people who know something about it.) That’s why Hector Berlioz can write a brilliant symphony based on a trite, overwrought story of his own devising. Ultimately the audience is not experiencing a narrative, they’re experiencing something else. To delve too deeply into Berlioz’s story (or for that matter, the plots of most operas) would be to miss the point. Taken out of context, the story is trite. In context, it’s sublime. Berlioz could’ve written a novel but he didn’t; he knew better. The same applies to, say, Mahler.

Phew, we’ve made it back to Ken Russell.

Now you can see why film is a risky medium in which to attempt an analysis of a piece of music: a filmmaker could easily throw the narrative elements of a symphony up on a screen, but in doing so he would be presenting them in a context that they weren’t meant for, thereby casting the music in a less-than-favourable light.

Russell veers dangerously close to this in parts of Mahler. But in one scene, Russell’s analysis actually works.

The feat occurs in one of Russell’s famous fantasy sequences, following Mahler’s heart attack on a train. Here, Mahler (Robert Powell) envisions his own funeral, at which he is alive and trapped inside a casket. His wife, Alma (Georgina Hale), and her lover (Richard Morant) take delight in the proceedings.

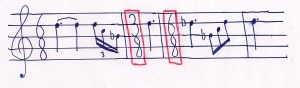

The sequence is scored largely by the slow movement of the First Symphony. This movement contains one of Mahler’s broader musical gestures: the inclusion of a mournful, minor-key adaptation of the folk song commonly known as “Frère Jacques.” The song is juxtaposed with a klezmer-like theme reflecting Mahler’s Jewish heritage. A standard interpretation of this movement holds that “Frère Jacques” may have originated as a tune sung by Catholics to taunt Jews. Thus, Mahler’s juxtaposition reflects a conflict that, as a Viennese Jew who converted to Catholicism for professional reasons, Mahler would have known well.

The consequences of Mahler’s heritage and conversion is a prominent theme in Russell’s film, but here, he ignores that element of the First Symphony. The sequence instead presents Mahler’s music as the same sort of Freudian dreamscape that Russell is so adept at creating. Russell uses the image of a vagabond figure (Ronald Pickup) from an earlier scene to connect the funeral to “Frère Jacques.” The vagabond was previously introduced in a flashback to Mahler’s youth, in which he teaches Mahler about the natural world, all the while playing “Frère Jacques” obsessively on his squeezebox. He appears playing his instrument atop a tall tombstone during Mahler’s funeral procession.

This image points out a specific feature of the music: the way Mahler has twisted “Frère Jacques” into a minor key. Perhaps the best way to explain it is this:

“Frère Jacques” = childhood = vagabond

minor key = death = tombstone

Thus,

vagabond + tombstone = “Frère Jacques” in a minor key

So, Russell is speculating about Mahler’s creative process and laying it bare on the screen: images collide in Mahler’s subconscious, and out comes music. The music reflects the odd juxtaposition between the images by producing its own odd juxtapositions.

Even if Russell’s analysis is unconvincing, you have to admire his method. He basically reverse-engineers Mahler’s music by putting it back inside his head. That’s pretty clever.