This is the second part of a retrospective on the complete works of the indie game studio Simogo. Part one dealt with their first three games. This part will cover Year Walk, DEVICE 6 and The Sailor’s Dream. It contains full spoilers for all of them.

Year Walk (2013)

The three games that predate Year Walk in the Simogo catalogue are all love songs to the smartphone. You might expect that the novelty of the touchscreen, the quality that made Bumpy Road a success, would have worn off by 2013. Nevertheless, Simogo spent the second phase of their career continuing to mine for novelty in the physicality of the smartphone. This still-new technology had already become mundane, so the new challenge was to create experiences for them that cut through the mundanity and made them feel surprising again.

If that’s the key theme of Simogo’s second era, then the mobile version of Year Walk remains the definitive one. Year Walk has escaped its origins as a mobile game more successfully than any other pre-Sayonara Simogo title: it exists in two dedicated ports for PC and Wii U. But we’ll be glossing over those ports in favour of the iOS original, because that’s the one that shares a continuity of purpose with the two narrative-focussed mobile games that came immediately after.

This version of the game is split in two unequal parts: the game itself, and a chalk-dry secondary app called the Year Walk Companion, featuring short encyclopaedia articles on the folkloric characters that appear in the story. These two apps are so dramatically asymmetrical, one so lavishly designed and the other so plain, that it’s easy to miss the fact that their user interfaces are exactly the same. In Year Walk, you scroll the game’s first-person perspective from left to right, exploring horizontal corridors that give the option of shifting to a new corridor by swiping vertically at specific moments. The Companion offers a menu of articles that you scroll between horizontally and select by swiping upwards. This mechanical similarity is the first suggestion that the Companion may be more than it seems: an integral part of the game, and not just a dutiful infotainment product like the ones you might download to Enhance Your Experience of a public museum or art gallery.

But the game itself is your first point of contact. It opens with the sound of a film projector, and white-on-black intertitles like in an old silent movie. The whole game has the flicker of cinema, though it commits to this premise only about as much as Super Mario Bros. 3 commits to its evocation of the theatre. It also resembles a children’s pop-up book at times, and it never really pretends to be anything other than a straightforward point-and-click adventure game with fairly standard puzzles. You play as an initially unnamed protagonist, undertaking a ritual called the year walk. To complete the ritual you must wander the haunted woods at night, meeting creatures of varying malevolence. At the ritual’s conclusion, you will presumably be confronted by a truth that you’ve been searching for, or avoiding.

The story is threadbare by design. It was based on an unproduced screenplay by Simogo’s collaborator Jonas Terestad, with the details pared away by Simon Flesser until all that remained was the protagonist’s motivation: he’s in love with the miller’s daughter, but she’s engaged to another man. You meet the miller’s daughter once at the start of Year Walk, and once more at the end. The hard truth we encounter at the end of the ritual is that she will fall out of love with the protagonist in the new year. The game’s final revelation is that the miller’s daughter dies for this transgression against male desire, murdered by the protagonist in the morning.

Edgar Allan Poe wrote that “the death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.” But it’s possible that you need to be alive in the 19th century and you need to be the greatest gothic writer of all time for this to be true.

It isn’t the story that sticks with you after a playthrough of Year Walk. Nor is it the puzzles, really, which are quite simple. This game doesn’t have the self-guided difficulty scaling of Beat Sneak Bandit and Sayonara Wild Hearts baked into it. I suspect it’s too brief and linear to support that kind of approach anyway. The puzzles are easy enough to provide a few moments of friction along the way to the story’s conclusion, which every player should be able to see.

What sticks is the visionary quality of your encounters in the mythical forest. Many familiar stories position the forest as a threshold between the mundane world and the fantastical, but these Swedish woods are darker and chillier than the lotusland of A Midsummer Night’s Dream or even the enchanted forests of the Grimm fairy tales. Simogo brings it to life with a cut paper art style reminiscent of the German shadow-play filmmaker Lotte Reineger and the Soviet animator Yuri Norstein. Simogo’s love of paper and other physical materials has been visible since the arts and crafts-inspired Kosmo Spin, but never more so than in Year Walk. The art is deeply expressive: every frame is suffused with wintry melancholy, underpinned by a soundtrack of whistling wind and snow crunching underfoot.

Throughout the ritual you meet the Huldra, a figure of threatening sexuality; the Brook Horse, a guardian of the drowned; the Mylings, spirits of murdered children; the Night Raven, an omen of death; and the Church Grim, a gatekeeper at the edge of revelation. Of these, the encounter with the Brook Horse and his wayward Mylings is the most memorable, for its puzzle mechanics and its character design alike. The besuited Brook Horse stands waist-deep in the stream that runs through the forest, asking you wordlessly to find the four Mylings hiding in the woods. Each of them requires a different way of physically interacting with the phone, like turning it upside down or scrolling the environment past its ostensible edge. They’re simple puzzles, but the way that they break verisimilitude by making you think about the physical object you’re holding adds to the uncanny atmosphere. What exactly is the player character doing when you turn your phone upside down? The player and the protagonist are visibly distinct from each other in these moments, purposely breaking immersion. It’ll happen again.

The sought-after revelation occurs in the final encounter with the Church Grim, during which the scissors-and-paper physicality of the world dissolves into 3D abstraction. Everything that has defined the game previously is gone. The puzzles cease to be puzzles in any meaningful sense, replaced by frictionless tactile moments of the sort that will be taken up with different degrees of success in Genesis Noir, A Memoir Blue and the flashback sequences in What Remains of Edith Finch. This presentation–a clean break with the game’s previous aesthetic and logic–helps to obscure the straightforward gothic romance of the narrative, which reaches its turning point here. When Year Walk doesn’t rely on words, it is fascinatingly obtuse and elliptical. When it does, it displays the five words “I don’t love you anymore” each on its own emphatic screen. A pool of blood spreads out around the body of a girl, and Jonathan Eng sings over the credits. (Incidentally, the first great Simogo musical number is a Year Walk song, but it isn’t this one. It’s “Myling Lullaby,” the promotional single that isn’t included in the game.)

So what is this ritual we’ve been undertaking? This ending leaves open the possibility of a somewhat tired psychological interpretation, that all the odd things we’ve seen are the product of a deranged mind. But something strange happens after the credits: an unknown voice speaks to us through onscreen text, entreating us to consult the Companion, where a secret passcode will enlighten us further.

The Companion’s blandness is a deeply committed feint. It is so incredibly halfhearted on its face that it almost feels like it was made to fulfil the requirements of a grant: like the Swedish government gave Simogo a few thousand euros to edutain the world with Sweden’s bizarre, forgotten myths. But this mundane supplement contains the secret that makes Year Walk into something more than a gothic point-and-click with a clichéd psychological twist. For reasons not supported by verisimilitude, there’s a login screen in the Companion that leads to the notes of its fictional author, Theodor Almsten. Almsten is a scholar of Swedish folklore whose investigations into the little known ritual of year walking led him to discover the story of Daniel Svensson, a young man who was executed for the murder of the miller’s daughter after undertaking the year walk. This is the name of our previously nameless protagonist.

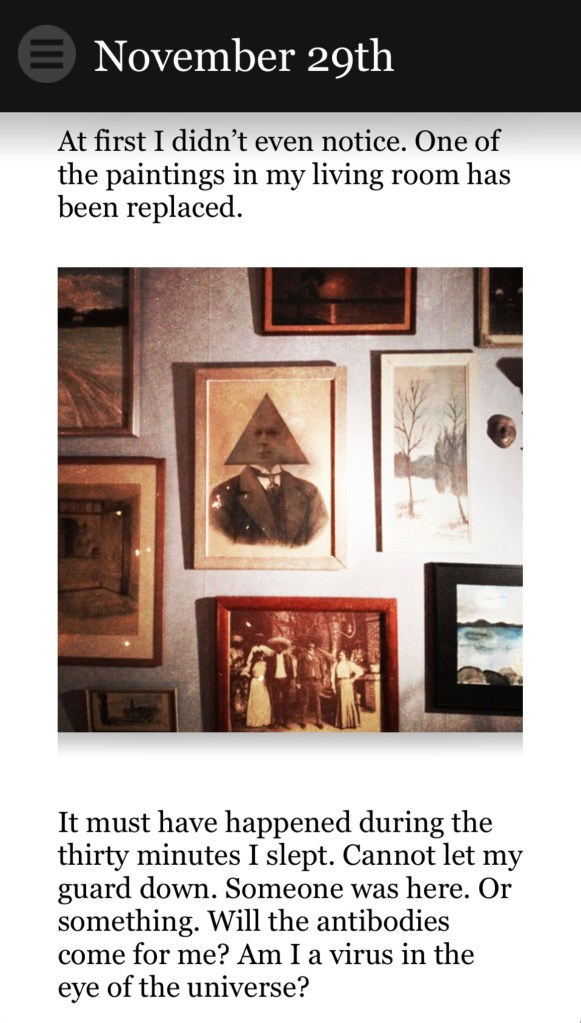

Almsten’s notes contain the best puzzle in Year Walk. After his discovery, strange things start happening to Almsten. He feels like he’s being watched, and a sequence of strange shapes begins showing up in his life: in drawings he makes in his sleep, on paintings that appear unexpectedly on his wall, tattooed on his skin. He realizes–without saying it explicitly and ruining the puzzle for us–that these shapes are the combination to open the mysterious wooden box he found in the woods near Daniel’s hometown.

We’ve seen this box before. It’s one of the first things you encounter in a playthrough of the main game, sitting there perfectly solvable from the moment you take control of the character, like the final puzzles in Myst and Outer Wilds. You might not think about it at the time, but the box looks odd. It doesn’t fit into the environment. It’s not hovering, exactly, but it’s the one thing in the game that looks like it hasn’t been blended in with the rest of the world: just an asset superimposed on a background. It’s uncanny. It only becomes more uncanny when you open the box–because who is opening the box, exactly? Daniel? How would Daniel know the combination? Does he, in the 19th century, have a smartphone with a copy of the Year Walk Companion? And by the way, who did Theodor Almsten actually get in touch with in that vision after the end credits? Presumably the Companion’s login passcode would be useless to Daniel.

A somewhat underdeveloped thread in Year Walk concerns the idea that the year walk ritual causes a sort of “system error” in the universe: that it causes verisimilitude itself to crash. The game’s final resolution–its “true” ending–involves a connection between two characters: Daniel Svensson and Theodor Almsten. From more than a century in the future, Almsten entreats Svensson to appease the (evidently quite real) forest creatures’ bloodlust with his own life rather than an innocent girl’s, changing history. But this connection requires the intervention of a third figure: us. In order for Daniel to know the combination to the uncanny wooden box floating at a fixed point in space, Almsten must reveal his notes to us, through the medium of an iOS app. You may recall in this moment the immersion-breaking Myling puzzles, or that notion of a “system error” in the universe. Year Walk’s true ending emphasizes the softwareness of the software: a move that Simogo is still finding new ways to pull as of 2024.

Year Walk marks the first time that Simogo let the fiction overflow its banks. It overflows in the form of the Companion, and various Blair Witch-style guerilla marketing. One final notable piece of Year Walk ephemera emerged in conjunction with the release of the Wii U port: the short story collection Bedtime Stories for Awful Children. These stories are fairly self-contained and don’t pull any of the Companion’s metafictional tricks–except in the sense that all scary folktales are frightening because they live on the border between fiction and reality. Year Walk is unsettling for the same reason that ghost stories are to children: because the storyteller swears it’s true.

DEVICE 6 (2013)

“Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

— Lewis Carroll

About midway through the development of Simogo’s fifth game, Edward Snowden leaked a massive trove of documents. It’s not like people weren’t already wondering whether their phones were spying on them. But suddenly, the efficacy of the smartphone as a surveillance device was a matter of public record. Simogo’s catalogue of mobile games up to Year Walk is an extended proof of concept for the smartphone as a Fun Little Gizmo: “Hey, look what this thing can do!” exclaimed over and over again to curiously undiminishing returns. By late 2013, the atmosphere had changed. DEVICE 6 asserts even more strongly than its predecessors that the smartphone is capable of just about anything. But this time, “just about anything” includes wanton surveillance, mind control, and the total collapse of reality into narratives that serve capitalism.

The smartphone has been the main character of this story since the start. We’ve arrived at its heel turn.

DEVICE 6 begins with a simple request: to hold the phone six inches from your face and press a button. When you do, the phone begins making scanning noises, and red lines flash across the screen like a sinister photocopier. The game then identifies you as “Player249,” leaving you to wonder what actually transpired here. Of course, the answer is nothing. The app doesn’t have access to your phone’s camera, and the red photocopier beams that appear on the screen couldn’t possibly have a function.

Or could they? DEVICE 6 constantly brings to mind Arthur C. Clarke’s famous assertion that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Nobody really knows how their smartphone works, so it may as well be magic. And in the post-Snowden era it may as well be black magic. This is DEVICE 6’s most fundamental trick: it leverages your distrust of technology to make you believe the game is doing things it can’t. It’s barely suspension of disbelief. Your phone really is spying on you. You know it is. You read it in the newspaper. The phone game knows your face.

(Like Bumpy Road, elements of DEVICE 6 don’t work as well on modern smartphones–but not for any mechanical reason. In this case, the sinister novelty of DEVICE 6’s opening is blunted by the fact that our phones actually are constantly looking at our faces now, in lieu of passcodes. We’re used to it. The fact that this moment is less upsetting than it once was is upsetting in itself.)

Moments like the opening face scanning sequence serve as interstitials throughout DEVICE 6. Between chapters, you’re given surveys by a suspiciously friendly corporate entity, each of which suggests in a slightly different way that your device is doing impossible things.

Meanwhile, you read the most esoteric ebook ever devised. DEVICE 6’s story is a mishmash of adventure game clichés concerning an amnesiac called Anna, who has to solve a bunch of escape room puzzles to discover why she’s been brought to this unfamiliar island. But as with Year Walk, it’s all in the telling–which finally brings us to the game’s main selling point: the text of DEVICE 6 doubles as both story and map. As Anna moves through the space, sentences stretch out into long, one-line hallways and stack into paragraph-rooms. At times, the text becomes a staircase or an elevator. Sometimes it turns corners, or branches into forking paths. Time and space collapse into an approximate representation of both at once. And yet, as schematically ambitious as it is, DEVICE 6 is simpler in certain respects than any of its predecessors. As much as it makes you twist and turn your phone around, it doesn’t actually use the motion sensors at all. And it is, after all, mainly just text.

At the time, DEVICE 6 was part of a discourse about the re-emergence of “interactive fiction.” Games composed mainly of text have never ceased to exist, but in 2013 there was reason to believe a renaissance was underway: Twine; Inkle; Fallen London; A Dark Room. DEVICE 6, which unexpectedly became Simogo’s biggest hit to date, was part of an unlikely trend. But DEVICE 6 also stands apart from the trend. It has different priorities from most of the other totems of the IF Renaissance. As the revered IF writer Emily Short noted, DEVICE 6 is first and foremost a “beautiful piece of typographical design.” It doesn’t offer branching story threads, except in a rare few instances that always require both branches to be explored. It leaves effectively no space for role playing, purposely separating the player and the player character for thematic reasons, similar to Year Walk. It is, figuratively if not literally, a linear story interspersed with light puzzles. It feels less like 80 Days than like the New York Times’ “Snow Fall” (the Train Pulling into a Station of high-budget online journalism).

DEVICE 6’s interactivity is subtle. It’s not so much about the tasks you are required to undertake or the choices you are allowed to make. It’s about the relationship it forges with the player: the intense awareness it fosters that you are engaging with technology. Specifically, you are engaging with a kind of technology that Steve Jobs wants you to be completely unaware of. Simogo is once again emphasising the softwareness of the software.

(This is another trend that DEVICE 6 was unexpectedly part of: a vogue for metafiction. 2013 also saw the full release of The Stanley Parable and the first two episodes of Kentucky Route Zero. The following five years would bring a flood of acclaimed metafictional games including Undertale, which follows in DEVICE 6’s footsteps by daring the player to disbelieve its reality.)

Scattered throughout the game’s text are schematics for, count them, six different devices that factor into the narrative, one per chapter. Learning what each device does in sequence gradually changes the way that you read the story. It becomes clear that the text we’re reading isn’t a mere pre-rendered story: it is the live feed of Anna’s actual experiences as she makes her way through the island’s trials on the other side of the world. A shadowy group called HAT has installed a number of clever devices in her brain that convert her inner monologue into text and broadcast what she sees and hears to our screen. More troubling still: one of these devices allows us a limited amount of control over Anna, which is how we can participate in solving the puzzles.

Learning about this succession of devices is the real story of DEVICE 6. Until close to the end, nothing much happens to Anna, really. But we grow more invested–more complicit–as we understand the nature of our interaction with the game. Of course, this is only as true as the facial scan at the beginning. But the fiction has overflowed its banks again, just like at the end of Year Walk, and this time the overflowing has been aided by real-life revelations that your phone is up to more than you know. Believing the impossible isn’t so hard.

This specific type of metafiction, where the story seems to spill uncannily into the real world, is the main thing that DEVICE 6 shares with Year Walk. But where Year Walk revelled in the moments where verisimilitude gave way, DEVICE 6 takes great pains to fill in the gaps that its predecessor left open. In Year Walk, Simogo handwaved away the game’s thorniest questions (“How does this character know how to open this box?”) with talk about a “system error” in the universe. Then, they hung a lampshade on their own handwaving by naming their game after its biggest handwave.

There is no such handwaving in DEVICE 6. The numbered devices we encounter in sequence throughout the chapters exist to precisely map Anna’s experiences onto the way we experience them on the screen: to narrow the distance between the map and the territory; the story and the telling of the story; the signifier and the signified. Year Walk leaves open questions for the player to puzzle out in the shower. DEVICE 6 goes so far in the opposite direction that it provides an in-universe answer to the most basic question in semiotics: what is the relationship between the furry animal that lives in my house, and the symbols “D,” “O” and “G?” (They’re related because DEVICE 1 relates them to each other, naturally.)

Anna’s story culminates in an encounter with DEVICE 6 itself. It serves as the central unit of HAT’s surveillance operation, master control for all of their other devices, a storage tank for the human sensory experiences they’ve collectively sucked up, and an object of worship for the members of HAT. By refusing to worship it as well, Anna seals her fate. The epilogue shows us a contradiction: one of the little devices in Anna’s brain continues to broadcast normally, showing us the reality of what she sees, but another device has been overridden by HAT. So, while the text gives Anna a happy ending where a sea captain answers her distress call, the sound and images show her true fate as a man in a bowler hat raises a pistol and shoots.

In the 2016 documentary HyperNormalisation, Adam Curtis argues that governments and corporate interests have successfully mediated our perception of reality by providing us with simplified narratives that deny the complexity and unpredictability of the real world. Many of his examples come from the Soviet Union and the internet, two places where it gradually became commonplace to deny the reality in front of your eyes. The epilogue of DEVICE 6 illustrates a rather Soviet cognitive dissonance. The story is allowed to end in a way that we know is untrue–but having no alternative, we proceed regardless. In 2013, three years before HyperNormalisation, it was less obvious that tech companies were playing a profound role in this flattening of the world. Nevertheless, DEVICE 6 managed to depict exactly this: a cultish organization developing technologies to filter and depict reality in a way that suits their own interests.

As a gift for playing through to the end, our corporate friends offer to send us a creepy doll in the mail. We know what this doll does. Once we receive it, it will knock us unconscious so that HAT can kidnap and forcibly “enhance” us with their horrible machines. We will be flown to the island, and the cycle will begin anew. Should you decide to play again, the Saul Bass-inspired opening cinematic now takes on a new meaning. What had initially seemed like a random parade of images now clearly depicts Anna’s kidnapping, as well as the player’s own eventual fate when that doll arrives in a few business days. At this point, the barrier between the fictional world and the real one has become precariously thin. Depending on how successful the game has been at suspending your disbelief, you may fear to open your own mailbox.

In 2013, DEVICE 6 seemed so deeply of its moment that it risked dating itself immediately. But we are still living in DEVICE 6’s moment: our realities have become even more strictly mediated by filtered streams of information emerging from consumer electronics, and we have collectively become much better at believing impossible things.

The Sailor’s Dream (2014)

Having thoroughly vilified the very technology that enabled their success, what was Simogo to do? Just keep working. Nothing in Simogo’s copious online documentation of their creative process indicates that they seriously considered moving away from mobile games after DEVICE 6: no hint that the dystopian possibilities they entertained in their fiction felt pressing enough in real life to prompt a clean break with smartphones.

Still, looking backwards from 2024, The Sailor’s Dream feels like the end of something. Simogo’s major releases since then have moved gradually away from smartphones: Sayonara Wild Hearts was their first game to initially launch on consoles, and Lorelei and the Laser Eyes is seemingly not coming to mobile at all. Aside from the spontaneous experiment that became SPL-T, they would never make a mobile-first game again. That knowledge lends an elegiac quality to The Sailor’s Dream: a sense that we are witnessing a fond memory from well after the fact.

But that elegiac quality was there from the start. This game’s atmosphere isn’t haunted in the same way that Year Walk was: there are no threatening or inexplicable creatures here. Instead, The Sailor’s Dream is populated with sad ghosts and wistful recollections of happier times. Our sole objective is to explore a handful of creaky-floored environments, all deserted. The point-and-click mechanics and escape room puzzles of the last two games are gone, but both games’ navigation mechanics are back. To travel the ocean overworld we scroll horizontally and swipe vertically to travel to a new area, like in Year Walk. And the game’s interiors navigate like a more pictorial DEVICE 6: networks of illustrated rooms, connected by scrollable pathways and graphical crossroads.

The rooms inside these mysterious island dream spaces are filled with symbols and memories. If you take the locations in the order they’re given, the first interactable item you’re likely to encounter is an empty picture frame. Its descriptive text details the photograph it used to hold, of a woman and a girl on a cliff: “The woman sings an old sea shanty and the girl wishes she was an explorer of the seas… just as the girl starts to feel cold, the woman wraps her arms around her.” That’s a lot of information to glean from considering a photograph that isn’t even there. This happens again and again in The Sailor’s Dream: even in the vividness of this dream world, memories present themselves as absences and diminishments. We don’t see a photograph of the woman and child, just the empty frame. We don’t see the kitchen table around which the family gathered, just the driftwood it eventually became. Even in dreams, the life has drained out of these places. But by the same logic, every object contained within The Sailor’s Dream, no matter how abstract or phantasmal, is freighted with potential meaning. Everything is more than it is: a piece of driftwood an elegy for a family dinner; an empty picture frame an elegy for an embrace on a cliff.

These brief snippets of descriptive text begin to suggest a story involving three people: a girl, a woman and a man. They also contain hints about other potential ways we might learn about these people. Firstly, there’s a print button at the bottom of each text snippet. This is the only time Simogo engaged with Apple’s AirPrint system: this print button allows you to view and, for some reason, print the girl’s drawings of the people and places in this story. We learn as we progress through the game that the story’s other two main characters have their own preferred media for personal expression. An old seaman is rumoured to broadcast on the radio every hour, on the hour. And somebody swears that the woman who lives on the cliff has been singing into a bottle and flinging it into the ocean, once per day.

In the broadest possible sense, The Sailor’s Dream elaborates on the formula established by Gone Home the previous year. That game had invited the player to explore an environment full of telling details, and to gradually learn the story of a family. Each family member’s story was told in a slightly different narrative register: YA coming of age story; trashy romance; multi-generational novel. The Sailor’s Dream extends this approach outwards so each character’s story is told in a different medium altogether: drawings, spoken language, and songs.

The woman’s bottles are easily discovered: after a certain point they start appearing in the game at the rate of exactly one per real-world day, and they do in fact contain songs. This is how we learn the story of the woman who lives on the cliff. Learning the story of the old seaman is the closest thing The Sailor’s Dream has to a puzzle. There’s an odd clock inside a shack on one of the smaller islands. At the top of the hour, again according to the real-world time, the clock’s radio flips on and a wistful man with a deep, rustic voice talks to nobody in particular about his lost love.

The fact that these two elements of the game correspond to the real-world date and time is the only way that The Sailor’s Dream allows the fiction to overflow its banks. The story here is essentially self-contained, but it invites you to check in with it periodically as you would a recurring dream. Every morning when you wake up, you’ll eventually remember that a new bottle has plunged into the waters of the dream world. And throughout the day, you’ll occasionally notice that it’s close to the start of a new hour, and you’ll know that in another reality, a man on a ship is about to broadcast his feelings over the shortwave. Discovering all of these bottles and broadcasts is part of the game’s critical path: the credits won’t roll until you do. Of course, it’s possible to brute force your way to completion in a single sitting if you mess with your phone’s date and time settings. But doing that would mean treating The Sailor’s Dream like a video game, and not the pocket universe it means to be.

The story we discover is a patchwork nautical melodrama: Breaking the Waves via dream logic. A beautiful woman meets the man of her dreams, and they live together in a cliff-top house overlooking the sea. They informally adopt a young girl during the summers, they get a dog named Archibald, and they live together in domestic bliss for one quarter of the year. The rest of the year, the girl is elsewhere and the man frequently has to be away at sea. The woman is mostly alone in that house. She comes to hate the sea, and the solitude. One night, the man is getting tossed around by a particularly vicious storm. He’s in the cargo hold when the ship tilts violently and a crate carries off his arm–the arm where he’s tattooed his loved one’s face. At this moment he knows, as we come to learn, that his beloved has thrown herself off the cliff.

We experience this story mainly through the eyes of the girl the couple adopts. It is her dream we’re in, her faded memories we discover, and her drawings we find. We learn that when she’s not with the couple in the cliff-top house, she spends most of the year in an institution. Evidently she has a history of pyromania. She hates the institution, and the doctor who asks her endless questions about her dreams. But there is one friendly guard, who regales her with stories about his beloved rowboat, which he’s named Lily Christine. The guard affectionately calls the girl “Sailor,” and brings her paper to draw on. When her mother figure dies, she watches as the pallbearers carry an empty coffin down the street, and she burns the cliff-top house to the ground.

The old seaman’s radio broadcasts come to us from a ship on the open sea, sometime long after the rest of the story has come and gone. He speaks with a voice of tired experience. He has little interest in his crewmates, who try in vain to coax him into a game of cards. The Jack Russell Terrier onboard his latest ship can’t compare with the memory of Archibald. Nothing interests him much except for reflecting on his great love. Like another ancient mariner, he’s compelled to relate his own tragedy to anybody who’ll listen. But unlike Coleridge’s mariner, this one isn’t guaranteed an audience. He speaks his tragedy into the static and is audible only in dreams.

It’s the woman’s story that’s the most memorable, not only because it’s the most tragic, but because it is delivered in the most memorable way. The songwriter Jonathan Eng has been in Simogo’s orbit since the promotional cycle for Kosmo Spin, and he’s been involved in every subsequent game in one way or another. (He even appears as himself in DEVICE 6–a rare honour for video game composers who didn’t work on Chrono Trigger.) But The Sailor’s Dream is the point where he becomes indispensable: as valuable a collaborator for Simogo as Ben Babbitt is for Cardboard Computer. It is rare for a video game to have songs–i.e. true songs, with lyrics, that maintain focus and aren’t just window dressing or a glib joke over the end credits. And it is vanishingly rare for these songs to be excellent.

The Sailor’s Dream’s songs in bottles tell their story with Sondheim-like efficiency. On the OST, they are simply named for the days of the week on which they appear in the game. On Monday and Tuesday, the woman sings of her early life: yearning for the sea against her family’s wishes, and finding a comfortable home in a friendly seaside town. She assembles her makeshift family on Wednesday and Thursday, meeting a handsome sailor at a dance and taking a needful child under her wing. On Friday, we hear one of Eng’s most satisfying songwriterly flourishes: he extends the length of the final chorus to accommodate the woman’s sincerest single utterance:

As the sun slowly sinks, I can’t help but to think

That we’re truly each other’s most valuable things

They say time can’t be stopped, but I’ll give it a try

As the last summer’s night passes by

Saturday brings rage. The woman rails against the sea and the promises her loved one should have known he couldn’t keep. Finally, Sunday marks the end of the woman’s life. Without this song, it’s possible the whole game wouldn’t work. We hear very little of what the woman’s life is like after her husband goes to sea. The rest of the game largely declines to give voice to her struggle. It takes Jonathan Eng exactly four lines to make up for this:

This house was once full of wishes and desire

But all life died out, only ghosts come through the door

Now it’s a shell that’s just waiting for the fire

Nobody lives in this house anymore

You could argue it’s troublesome that The Sailor’s Dream is the third Simogo game in a row that revolves around the violent death of a woman, and this one in particular may be a problematically romantic depiction of suicide. But the teenage Decemberists fan deep inside me is powerless against this. Eng’s song is a beautiful illustration of grief, longing, and the difference between how you hoped it would be and how it turned out. It completes the woman’s emotional arc, and finds the humanity in a very melodramatic ending.

In spite of its melodrama, The Sailor’s Dream is Simogo’s subtlest creation, replete with easily ignored detail: the symbols in the UI; the sound and feel of the swiping motion; the subtle fade between photorealistic ocean and painterly sky on the overworld screen. It is their least gamelike creation but their most expressive, like the Church Grim encounter in Year Walk expanded into a whole game. Its rooms are filled not with puzzles, but with bespoke software instruments that allow you to improvise melodies overtop of Eng’s score, wheels to spin, windows to tap on. The narrative doesn’t depend on this interactivity to come through, but the experience of finding a room full of glowing musical cubes is equally beguiling and evocative as any of Simogo’s now-absent puzzles.

Since The Sailor’s Dream is driven so heavily by atmosphere and music, it isn’t surprising that Simogo spun it off into a podcast. The Lighthouse Painting is part of the post-Serial podcasting boom of 2015, when everybody remembered the storytelling power of audio all at once, in spite of the fact that podcasts had already been around for well over a decade and radio hadn’t gone anywhere. It focuses on a minor character in the game: the sympathetic guard at the facility where the girl is being held. Over four miniature episodes, the now-former guard tells us a maritime tall tale about a girl who paints with watercolours made from the ocean. The ocean, vengeful over its stolen water, repossesses whatever she paints, including her mother and the lighthouse where she lives.

The Lighthouse Painting is only tangentially connected to The Sailor’s Dream through its narrator and his rowboat, and a couple of repeating themes from Eng. But it expands on the game’s obsession with dreams and stories–it is only through these that the ocean takes on supernatural powers. Simogo only ventured into podcasting this one time, at the precise apex of the excitement about that medium.

Meanwhile, the apex of excitement about the smartphone had come and gone. The Sailor’s Dream is a bittersweet recollection of a time when it seemed novel to have a telephone that also worked as a day planner, played music and told the time. This miraculous device, which responded to the touch in precisely the way you expected, once seemed like it had limitless potential for designers and storytellers to bring their craft to new audiences. Those days are over. Nobody lives in this house anymore. Time for a new horizon.